By Ed Gross

May 24, 2018

Death at an early age has a tendency to preserve, and oftentimes enhance, a star's fame, whether from film (Marilyn Monroe, James Dean) or music (Elvis Presley and John Lennon immediately coming to mind). And then there's Bruce Lee, the Hong Kong-American actor and martial artist who, since his passing back in 1973, has only seen his star grow brighter, but under very different circumstances from most other people.

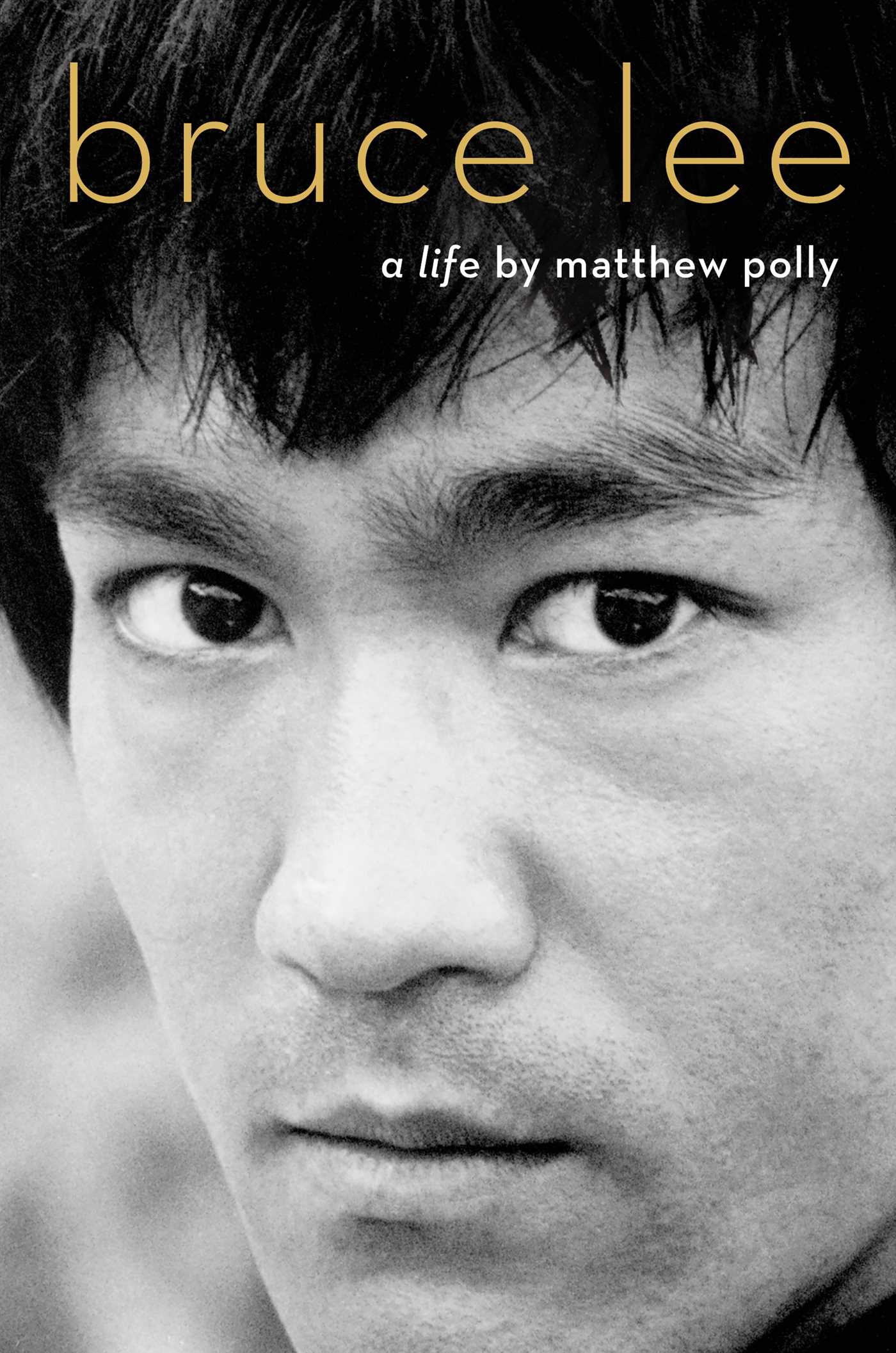

"He's the only iconic figure of the 20th century whose fame was almost entirely posthumous," offers Matthew Polly exclusively, whose exhaustive biography, Bruce Lee: A Life, will be published on June 5, 2018. "He died before the movie that made him famous — Enter the Dragon — actually made him famous, and there was no encounter with him beforehand as celebrity persona. People like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe were famous before they died early, but Bruce Lee, aside from viewers of The Green Hornet and a few martial arts fans, no one knew who he was. Enter the Dragon was our only text to understand him.

"Then," he adds, "the martial arts magazines ran with it and they turned him into the Patron Saint of Kung Fu, which is true as far as it goes, but the first huge revelation that came to me was when I was sitting in the Hong Kong Film Museum watching the 20 films he made as a child actor in Cantonese and Mandarin — not one of them had a single fight scene."

Revelations about his biographical subject came aplenty for Matthew, who spent nearly seven years researching and writing Bruce Lee: A Life, beginning with what he calls a "full career" of acting in which Bruce played "spunky orphans in melodramas and weepies."

"There was a sense," he explains, "that here's an actor who fell in love with the martial arts, and then merged his two obsessions by becoming a martial arts actor. That was a later phenomenon, but what he was first and foremost, with a father who was an actor, and growing up in the entertainment industry, was a child star. That gave me a sort of way to understand things that people had actually written out of his history, because it didn't fit with the Patron Saint of Kung Fu image. You know, that he had a Mercedes-Benz, and he bought a full mink coat, and he smoked a little dope, and he had a few extramarital affairs. His behavior as an adult was like Steve McQueen, who was his role model. He was a celebrity. He wasn't an aesthetic guru zen martial arts monk. That was the character he played in Enter the Dragon, but that'snot who he was as a person. As a person, he was an actor first chronologically, and then he beame a kung fu expert. If you think of him as a celebrity actor who's into kung fu, then he becomes like many actors at the time, but if you only think of him as the kung fu master who accidentally made films, then he becomes this distinct almost demi-god in the way the fans think of him. They think he's invincible. They sit around arguing if he could beat Iron Man in a fight."

Uh, no.

Early Days and The Green Hornet

Bruce was born on Nov. 27, 1940 in San Francisco's Chinatown to Hong Kong parents. He was raised in Kowloon, Hong Kong and remained there until his late teens. During that time, he was led to the acting life by his father and appeared in a variety of films, which, as Matthew has noted, had nothing to do with fighting. Real life was a little different. Finding himself involved in skirmishes with local gangs, he was taught to defend himself, which led to a deepening interest in the martial arts. For his own safety, at 18 his family sent him to America to live and work at Ruby Chow's restaurant in Seattle. He attended college, studying drama, philosophy and psychology, and it was there that he met his future wife, Linda Emery, the two of them eventually having a son (Brandon) and daughter (Shannon).

In 1959, Bruce began teaching martial arts in the form of Jun Fan Gung Gu, opening his own school in Seattle. His students grew and his school expanded to another location. At the same time, he began participating in karate tournaments and his style continued to evolve. Acting wasn't really of interest, though Bruce was drawn back to it for the superhero series The Green Hornet, which aired from 1966-67 and saw him as the sidekick to the title character (played by Van Williams).

"He had been offered the TV series Charlie Chan's Number One Son by William Dozier," Matthew says, referring to the producer of the Adam West Batman TV series, "which means that the very first part he thought he was going to get in Hollywood was a starring role in a TV series, which no Asian male actor had ever been given before. He thought he was going to step in and be the Jackie Robinson of Asian actors and knock it out of the park in this first one. But what happened was that they submitted that to ABC, and ABC said, 'No, we're not going to do a show with an unknown Chinese male lead,' and rejected it immediately. Then William Dozier said, 'Well, I've got this other one, The Green Hornet...,' and so in the very first experience he had in Hollywood, he went from being the lead of a TV show to the house boy."

Created for radio in the 1930s by George W. Trendle, the focus was on millionaire muckraking newspaper publisher Britt Reid, who, by night, became the masked Green Hornet, who waged a war against crime. His sidekick was Japanese valet Kato. Reid, incidentally, was designed to be great-nephew of Trendle's other creation, The Lone Ranger.

"Bruce was not happy," says Matthew. "He initially balked and insisted that the part had to be real. The truth is, Bruce didn't really have a choice. He was under contract to Dozier. Even if he could legally, he had a young wife, an infant child, and an empty bank account. But despite having no leverage, Bruce insisted he would only take the part if it was upgraded and modernized from the radio version where Kato's biggest moments came when Britt Reid, the publisher, barked, 'My car, Kato!', and Kato answered, 'Yessuh, Mistah Blitt.' He and Dozier worked together to make Kato sort of a weapon of the Green Hornet. You can tell on set that he was still uncomfortable with playing second fiddle, and I think that not only was it the sort of Chinese pride he had, but it was also just his personality. He just never liked being in second place. He was only comfortable when he was in charge."

A saving grace about The Green Hornet is that the character's creator, George W. Trendle, had the right to veto Dozier's idea to follow in the tradition of Batman and have the show take a campy, over-the-top approach. "Dozier was convinced that Trendle was wrong," says Matthew. "Trendle wanted it serious and Dozier wanted it more comic booky. By the end of the show, Bruce had mixed feelings, because he knew this was his big break and he would never have had a Hollywood career without this show, but it was not what he was initially promised. He struggled afterwards to find other parts, and people kept trying to cast him essentially as a version of Kato — the house boy to the white hero. At the same time, I think he enjoyed the experience. He realized it was a huge break. Actors spend their whole lives trying to be the second in a TV series. Still, after it was over he would say things like, 'The writing was terrible and they didn't give me much to do.'"

There was something of a silver lining to the fact that had done The Green Hornet, however, despite the fact it only lasted a single season. Matthew details, "Kato proved to be a more popular character than the Green Hornet. His character received way more fan mail from kids. More importantly to his future, Bruce and Kato were embraced by the small but growing American martial arts community, who had never before seen their art performed on-screen by one of their own. Overnight, Bruce Lee became the most famous martial artist in the country with profiles in Black Belt magazine and invitations to headline karate tournaments — a far cry from the 1964 Long Beach International Karate Championships two years earlier where he was a virtual unknown."

While he continued to teach (with celebrities starting to become his students), Bruce made TV guest appearances, garnered some small film roles, and choreographed fight scenes for Dean Martin's Matt Helm film, The Wrecking Crew, and A Walk in the Spring Rain, money definitely remained a problem. "The popularity of Kato as a character," Matthew says, "allowed Bruce to supplement his income with paid appearances across the country. He was invited to perform at fairs, malls and public parks. He appeared at store openings and rode on floats, often in Kato's dark suit, chauffeur's cap, and black mask. His asking price quickly rose to $4,000 for an afternoon's visit. But after The Green Hornet was canceled, big money invites for Kato slowly dried up."

Eventually, he returned to Hong Kong to star in a film he hoped would prove to Hollywood executives that he had the stuff stars were made of. That was 1971's The Big Boss, which broke box office records. Even more successful was the following year's Fist of Fury, which in turn allowed him to become the star, writer, choreographer, and director of 1972's Way of the Dragon. This one pit him against karate champion (and future actor) Chuck Norris, set against the backdrop of the Roman Coliseum.

From there he began shooting Game of Death, the concept of which saw him battling his way up through various levels of a pagoda, encountering a different martial arts master on each one as he makes his way to the top to retrieve an undescribed prize. But production stopped in November of 1972 when he was offered a contract by Warner Bros to star in the film Enter the Dragon. This was the opportunity that he imagined — and which proved true — would catapult him to a whole new level of stardom. Sadly, he never got the chance to experience that for himself, as he died on July 20, 1973, about a month before the film was released.

The Creation of a Legend

Which is the point that the legend of Bruce Lee first took root. Enter the Dragon, which had cost $850,000 to produce, has pulled in more than $200 million at the global box office, while at the same time securing his legacy — 45 years later, and still going strong.

"What's fascinating to me is that at that point, Bruce Lee suddenly becomes a character," Matthew offers. "They start making Bruce-sploitation movies, where he fights Dracula and James Bond, and suddenly he's become a fictional character. That only happened because there was no long history of seeing him on The Tonight Show or seeing him in gossip mags, or all of the things that accumulate around a celebrity so that we hold them distinct from the characters they play on screen."

Bruce had espoused a public philosophy, a seemingly deep insight to the human psyche, and yet his behaviors in everyday life painted a portrait of a man driven by the same foibles that most of us are. "He was very serious about his philosophy," says Matthew. "I would talk to people who were, like, 'Yeah, he just wouldn't shut up.' That's not somebody who's faking it, you know? Somebody who's constantly talking about it all the time is somebody who's a real believer. But I think psychologically speaking, he was trying to balance himself out. That, at root, the little dragon was a fire element. He had a hot temper. He burned the candle at both ends. He had this great charisma, star power, and all the imagery when people talk about Bruce is very fire-oriented. Yet what he talked about was, 'Be like water, my friend.' To me, I think that was him in some sense knowing what his weakness was, and trying through philosophy to balance himself out. So when you study his life, you see all those kind of firey things: the short temper, the getting into fights, the arguing with people above him. Then you hear his philosphy, which, again, is be like water; adapt, bend with the wind. We preach what we need to practice, right? If you listen to a man preach about not having extramarital affairs, you know what you're going to find out."

And all of this, Matthew emphasizes, is what drove him to write this biography to begin with: "The goal of the book is to show how Bruce was human, because I think his accomplishments are more remarkable if you treat him as a human being and see what he had to overcome in order to become the first Asian American to star in a Hollywood movie, as opposed to treating him as a super heroic character who just rolled out of bed one day and had this tremendous success."

Part of the challenge in doing so, however, is the difference between much of what is presented in Bruce Lee: A Life and the image that has been preserved and cultivated by Linda and Shannon Lee (Brandon, sadly, died accidentally while shooting the 1994 film The Crow). For instance, while Bruce's official cause of death was a cerebral edema, possibly triggered by narcotics in his system, word is that he died in the apartment of actress Betty Ting Pei, with whom he was reportedly having an affair — one of several that are chronicled in the biography.

Matthew points out that he spoke to both Linda and Shannon. "I like them both," he says, "and admire the way they've worked so hard to keep Bruce's image alive and talk about his philosophy and the values that he espoused. So, bracketing that, I was curious, because the image they presented is more like Saint Bruce. I wondered if it was monetary or if it was true belief, and when I talked to Linda, and was interviewing her, my feeling was, 'My God, she really does believe that he was perfect.' And she wasn't fully convinced he'd cheated on her when I interviewed her. I'd written a piece where I'd said Betty Ting Pei was his girlfriend, and she hadn't agreed to the interview until she read that piece, and she basically came in to correct me. She was, like, 'Well, we don't know if this is true,' and I asked, 'So you don't believe it?' 'Well, he was such a good father and such a good husband. I don't think he would do anything to hurt his family.' At that moment I was, like, 'Wow, okay.'

"Here's the thing," he elaborates. "I think to this day, he was the true love of her life; her first true love, and she just has a remarkable love for him. I've been at wakes for students of his, and she kind of offers up things that Bruce said, and I came away feeling, like, 'She's a bit of a high priestess of the Church of Bruce.' My point is, I think it's quite sincere. Secondarily, the Bruce Lee estate, as policy, doesn't get involved with anything that touches on his death — which involved the scandal. As a result, when you see anything that's been authorized by the estate, you'll get his whole life and then there's an ambulance driving by and it goes into the afterwards. So it creates a distorted image of who he was."

Just as distorted is the last day of his life, beginning with the fact that the production company Bruce worked with, Golden Harvest, had put out a statement saying he had died at home with his wife while walking in the garden. That story was "blown up" three days later by the press, so a new wave of alternative facts came out stating that Golden Harvest's Raymond Chow and Bruce had both gone to Betty's apartment for a business meeting and to offer her a role in Game of Death, which was going to resume filming.

"Raymond Chow doesn't go to business meetings at the apartment of B-list actors," Matthew notes. "No movie executive does that. He had meetings in fancy restaurants or at his office. But the second story held up for a really long time. No one believed it, but no one could puncture it, even though it was also made up. It was a slightly altered version in order to cover up the affair. Then, finally, when I interviewed Betty in 2013, that was the first time she told a Western reporter, 'Look, I was his girlfriend. He came over by himself.'"

Game of Death

In 1978, Bruce's last film, Game of Death, was released and it was nothing short of a disaster. Working with the footage that Bruce shot, and using a lookalike who really did not look anything like Bruce Lee, a story was cobbled together, the resulting film pretty much dismissed. "Every fan hates that movie," Matthew concurs. "Part of it is because there were 30 minutes of actual filming that Bruce had done, and they cut that down to seven or eight. At the very least they could've let the whole thing run as the last 30 minutes of the movie instead of what they did. When I talked to [associate producer] Andre Morgan, their view was they were in an impossible mess: 'He didn't have a script and we were trying to figure out how to put this together, and it was insanity. This was the best we could do.' The one thing I can say is, looking at other kung fu movies from that time, Game of Death is better than some of them.

"Admittedly," he adds with a laugh, "it's a really low bar. But they're well aware of the criticism, and Raymond Chow has said through the years, 'I never wanted to make the movie, but there were contracts with distributors and I felt like I had to.' You know things are uncomfortable when no one wants to claim credit for them in Hollywood, right?"

For the record, all of Bruce's footage was included in the 2000 movie documentary Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey, which allowed fans to experience the actor's intent as his character made his way up the pagoda. "What's amazing about it now," Matthew points out, "is that I'll tell friends what the idea was, and they're, like, 'Oh, that seems so hackneyed.' I'm, like, 'That's because everybody's copied it.' That movie was the basis of almost every single video game. Doom, you go in and you fight up levels. That's The Raid constantly. So he caught a real archetypal idea, but he couldn't figure out how to make it; the story concept eluded him while he was working on it. And it eluded them when they were trying in 1978 as well."

Not so elusive is Warrior, a forthcoming Cinemax series based on a concept by Bruce that is, according to the network, "set at the time of the Tong Wars in the late 1800s in San Francisco. The series follows a martial arts prodigy originating in China who moves to San Francisco and ends up becoming a hatchet man for the most powerful tong in Chinatown."

"This was something that Bruce pitched at the same time he was trying out for the TV series Kung Fu, which is why everyone gets confused about it and thinks that he created Kung Fu, because the two projects were very similar," says Matthew. "I do think there's a tendency when you're combing through someone's archives where you're, like, 'Here's a genius idea, and it's inspired by Bruce Lee.' From my research, he did a seven-page treatment proposal for Warrior, and he pitched it to Warner Bros. They ended up turning it down, because they were going to do Kung Fu instead."

A Debt Repaid

Matthew Polly, it should be pointed out, doesn't come to this biography as a guy who one day said, "Wouldn't it be great to write a book about Bruce Lee?" At 21, after finding inspiration from a Bruce Lee film, he traveled to China to train at the Shaolin Temple, which is the birthplace of Chan (Zen) Buddhism and kung fu itself. He stayed there for two years, being the first American to be accepted as a Shaolin disciple. The experience resulted in the 2007 book American Shaolin.

"There was a period where I didn't have a publisher for the Bruce Lee book," Matthew details, "and I wasn't sure the book was ever going to come out. Then we took it back to market and a couple of people said no. At the same time, I sometimes felt like Bruce's spirit was guiding me, though I'm sure that's just my imagintion. Then Simon & Schuster picked it up, so for me there's a certain sense of relief and satisfaction. And as someone who is still an unabashed Bruce Lee fan, I'm happy that he finally has a complete biography. You look at Steve McQueen, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean — all of these people have multiple really good biographies, and Bruce Lee couldn't have one? The Asian guy doesn't get invited to the biography table? That was what motivated the project. I was, like, 'Well, if no one else is going to do it, then I guess I'll do it.' So now that he has one, it feels like I've fulfilled what Bruce Lee gave to me. I've fulfilled my end of the bargain."

Bruce Lee: A Life will be available from booksellers on June 5.

No comments:

Post a Comment