Billy Graham, the Charlotte-born preacher whose pioneering talent for combining old-time religion and modern media made him the most famous evangelist in American history, died Wednesday at his home in Montreat.

Son Franklin Graham, in a memo to the staff at the Charlotte-based Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA), said the elder Graham, who was 99, died at 7:46 a.m. “due to complications of his advanced age.”

In the memo, Franklin Graham, who now heads the BGEA, also said that his father’s death “signals the passing of an era. But because of his faithfulness to the Lord Jesus Christ and God’s blessing upon the BGEA’s commitment to preach the Word in season and out of season, our worldwide evangelistic ministry continues around the world.”

And he announced in the memo the Bible verse the ministry will use for Billy Graham’s services is Revelation 14:13: “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord, that they may rest from their labors and their works follow them.”

Growing up on a dairy farm near what is now Park Road Shopping Center, Billy Graham’s first idea of heaven was playing baseball and courting girls. But after answering the altar call at a revival during the Depression, he went on to become a pastor to U.S. presidents and a globe-trotting preacher whose crusades altered lives.

In a career spanning more than 60 years, he took his simple Christian message to more than 84 million people in almost 60 countries – including multitudes of spiritually starved believers behind the communist Iron Curtain. Add those who heard him live, via satellite, and the numbers jump to 210 million people in 185 countries.

Always Billy, never the Rev. Graham, the humble but media-savvy Southern Baptist minister had little use for clerical garb or heavy theology. He even bypassed churches, preferring to deliver his spellbinding sermons in stadiums packed with people hungry to hear how much God loves them and how that very night they were being called to surrender their lives to Jesus Christ.

Over the decades, Graham also became the unofficial White House chaplain, participating in nine presidential inaugurations between 1965 and 2005 and offering spiritual guidance – and occasionally political advice – to Republican and Democratic presidents.

Mindful of Graham’s popularity, they often sought his blessing for their sometimes controversial decisions. This coziness with power brought Graham criticism in the 1960s and ’70s, when he refused to challenge President Lyndon Johnson on Vietnam and defended President Richard Nixon throughout the Watergate scandal.

Even into his 90s, when Graham rarely strayed from his mountaintop home in Montreat, presidents and presidential candidates came to him for prayer time and a photo opportunity. President Barack Obama visited in 2010. Two years later, Mitt Romney, then Obama’s GOP challenger, showed up, coming away with a virtual endorsement – a public sign to evangelical voters that it was OK to vote for a Mormon.

Also in 2012, a picture of Graham and words attributed to him were prominently featured in newspaper ads urging voters to pass a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage. Some Graham scholars at the time accused Graham’s son, Franklin, of using his father’s image to boost his own conservative causes and favored GOP candidates. But the younger Graham, who had by then inherited the leadership of the BGEA, disputed that, saying “Nobody kidnaps my Daddy.”

America’s religious revival

Graham made his first national splash on the eve of the 1950s, a decade in which America – then fighting a Cold War against atheistic communism – added “under God” to its Pledge of Allegiance and started printing “In God We Trust” on its paper currency.

The preacher who came to be called “America’s pastor” thrived in this climate of religious revival: His image showed up on magazine covers and in living rooms via the infant medium of television.

Evangelical Christians who had been ridiculed since the Scopes Monkey Trial of the 1920s for believing in the literal truth of the Scriptures suddenly saw Graham – one of their own – reading the Bible in the White House with President Dwight Eisenhower.

But if Graham’s charisma and friends in high places made him seem as contemporary as Elvis or “I Love Lucy,” his message to the masses was as old as the call to conversion in the letters of that other famous evangelist, Paul.

Jesus died on the cross for your sins, Graham told his audiences. Now it was decision time: Will you repent, turn your life over to Jesus and be saved?

“Time is running out!” he’d insist in that courtly Southern accent, holding the Bible open with one hand and chopping the air with the other. Graham would then issue his altar call, inviting those in attendance to come forward and commit their lives to Jesus.

“Don’t worry, they’ll wait for you,” he’d say as hundreds, even thousands, made their way down from the upper decks as the choir sang “Just As I Am” – a 19th-century English hymn that became part of the soundtrack for his crusades.

His style and plain Gospel message put off some intellectuals and theologians. But Graham never deviated from his approach. As he got older and times changed, though, his style softened. He went from a fiery by-the-Book conservative Protestant to a friend of other faiths, from a hawk on the Vietnam War to an advocate of nuclear disarmament, and from a finger-pointing voice-of-doom preacher to a gentle grandfather-figure who emphasized God’s love.

In the 1950s, Graham charged that Satan was the mastermind behind communism; in the 1980s, he defied many of his fellow evangelicals by traveling to Moscow to preach and attend a Soviet-approved peace conference.

“Here’s a man who’s never stopped growing,” observed Jim Wallis, editor of Sojourners, a left-leaning evangelical journal. “He listens. He’s changed and been touched by the people he’s preached to.”

Sticking with Nixon

On two of the major issues of his time, though, many say Graham changed too slowly. Even those who came to admire the evangelist said he was too timid on civil rights for African-Americans in the 1960s and too loyal, in the 1970s, to Nixon. Graham repeatedly held up the Republican president as a man of God, while behind the scenes Nixon was compiling an enemies list, engineering the Watergate cover-up and uttering profane expletives and anti-Semitic remarks in the Oval Office.

In fact, during a 1972 meeting with Nixon, Graham, sounding eager to please, joined in on the anti-Jewish talk. He apologized in 2002, when the White House tapes were made public.

“With Nixon, he should have been more like Nathan the prophet, the outsider who pointed his finger at the king,” Rabbi James Rudin of the American Jewish Committee once said. “Instead, Billy was inside the palace.”

On civil rights, the Graham of the 1950s refused to preach to segregated audiences. He insisted that God was color-blind, and befriended and promoted the young Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But in the 1960s, when King and his followers began going to jail for their nonviolent resistance to racist laws, Graham kept his distance.

“He didn’t like the marches,” said William Martin, author of “A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story,” the definitive biography. “He didn’t like the confrontational aspects of civil rights.”

Ruth and Billy Graham at their home in mountains of Buncombe County, North Carolina

A powerful teammate at home

Graham was never a one-man band.

He relied on an army of planners and promoters to arrange and publicize his crusades. Longtime associates Cliff Barrows, who directed the choirs, and George Beverly Shea, who sang the solos, were always there to offer the hymns that Graham’s fans came to expect.

And while Graham staged crusades around the world, his most important adviser – his wife, Ruth – stayed at home in the western North Carolina mountain town of Montreat. There, she raised their five children. She also clipped articles for him about the cities he’d next visit and studied the Bible that, according to Graham, she knew better than he did.

“Without her,” daughter Anne Graham Lotz once said, “Daddy’s ministry would not have been possible.”

Ruth Graham died in 2007, and Graham will be buried next to her, on the grounds of Charlotte’s Billy Graham Library. Like her, he will be laid to rest in a plywood coffin made by prison inmates.

Though Graham’s globe-trotting kept him away from his wife and children for months at a time, he always called North Carolina home. And he continued to return to Charlotte – the site of Graham crusades in 1947, 1958, 1972 and 1996.

A 2011 poll of Tar Heel residents proclaimed Graham the most popular person in the state, edging out longtime University of North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith and actor Andy Griffith.

The BGEA moved its headquarters from Minneapolis to Charlotte in 2004. And on June 5, 2007, the $27 million Billy Graham Library opened, drawing past U.S. presidents, celebrities and thousands of tourists to a barn-shaped building. Inside, it’s filled with everything from Graham’s 1983 Presidential Medal of Freedom to the engagement ring he gave Ruth.

The road to the museum: Billy Graham Parkway, a 4.8-mile boulevard in Charlotte that was dedicated in 1983.

Early revival lit his fire

William Franklin Graham Jr. was born Nov. 7, 1918 – four days before the Armistice that ended World War I. In those days, babies were often delivered at home. And so it was with Frank and Morrow Graham’s firstborn.

One of the early passions of “Billy Frank,” as he was called, was baseball. He shook hands with Babe Ruth when the home run king came through Charlotte. And though he wasn’t a natural athlete, Graham’s first career goal was to play ball in the majors.

Those ambitions started to change in 1934, when Graham, then 16, went to a revival on Pecan Avenue, near the edge of town. The star evangelist that night: the fiery Mordecai Ham, who preached in a 5,000-seat tin-roof tabernacle. One night, convinced he was a sinner, he answered the altar call. When the choir sang the words “Almost persuaded. … Almost – but lost!” Graham and a friend walked forward.

New denomination, new love

After high school, there was a brief stint as a door-to-door Fuller Brush salesman – Graham was the top seller in his region. But he soon began pursuing his new dream: to be a preacher.

Graham got his bachelor’s degree at Wheaton College, an evangelical school outside Chicago. It was there that he met Ruth McCue Bell, a fellow student who grew up in China, the daughter of Presbyterian medical missionaries.

Their first date: a Sunday afternoon performance of Handel’s “Messiah.”

On Aug. 13, 1943, they were married at Montreat Presbyterian Church in the small Western North Carolina town where Billy and Ruth would eventually build a mountaintop home.

Onto the national stage

The American mainstream began to embrace Graham in 1949. The place was Los Angeles. Graham had set up a giant tent for what he expected to be a three-week revival. But one night, Graham arrived to find the place hopping with reporters.

“You’ve been kissed by William Randolph Hearst,” one of them told Graham, referring to the media tycoon who owned a national chain of newspapers.

Hearst, who liked Graham’s strident anti-communism and religious zeal, had sent a memo to his minions, ordering them to build up the evangelist. His exact, now-famous words, which were printed on a Teletype and shown to Graham that night: “Puff Graham.”

With the press turning the spotlight his way, Graham’s revival drew 350,000 over eight weeks – and became the springboard for a lifetime of crusades.

In 1957, ABC offered Graham his first live TV exposure. The event: The “Gospel in Gotham,” Graham’s foray into New York City, where he conducted a 16-week crusade that drew 2.3 million people.

Graham’s fellow Bible believers, especially those in his native South, began to feel that Graham had ushered them out of the wilderness by giving their evangelical movement a public face and voice.

“He brought the evangelicals into the mainstream of American religion,” said Harvey Cox, former dean of Harvard Divinity School. “And he enabled a productive conversation between evangelicals and other streams of Christianity to flourish.”

Author Tony Campolo put it this way: “Billy Graham is the closest thing we evangelical Protestants have to a pope.”

But Graham wasn’t just a hit with evangelicals. In 1955, Americans named Graham one of the world’s 10 most admired men – the first of his record 61 mentions in the annual Gallup Poll list.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Billy Graham

Facing racial divisions

By the late 1950s, Graham had developed a reputation for refusing to preach to racially segregated crowds. It was a decision that brought him death threats.

“Christianity is not a white man’s religion, and don’t let anybody tell you that it’s black and white,” Graham preached. “Christ belongs to all people.”

In 1957, he was among those urging Eisenhower to send federal troops to Little Rock, Ark., to enforce desegregation of Central High School.

The same year, Graham also sent a letter to Dorothy Counts, a 15-year-old black girl in Charlotte who was spit on and heckled by whites as she walked to class at previously all-white Harding High School. “Those cowardly whites against you will never prosper because they are un-American and unfit to lead,” Graham’s letter said.

But Graham’s support for blacks’ quest for equality began to cool in the 1960s as the civil rights movement, grew more confrontational with its marches and nonviolent resistance.

By the ’60s, he had become a friend to presidents and a member of the establishment. Instead of challenging authority, his style was to work his inside channels – at the White House and in corporate America.

“The irony is that Billy Graham was more involved in King’s early phase, when it took a lot of courage to have such contacts, than in the ’60s,” King biographer Taylor Branch once said. “In the ’60s, Billy Graham was sticking to his things.”

Graham later said that his friend King had advised him to stay in the stadiums and leave the protests to King.

But several of King’s associates – including the Rev. Jesse Jackson and U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga. – have lamented that Graham did not appear at the 1963 March on Washington, when King gave his “I Have A Dream” speech.

With his white following, Graham “would have sent a most powerful message to this country” if he had been there to speak and pray, Lewis said later. “He would have moved us much faster.”

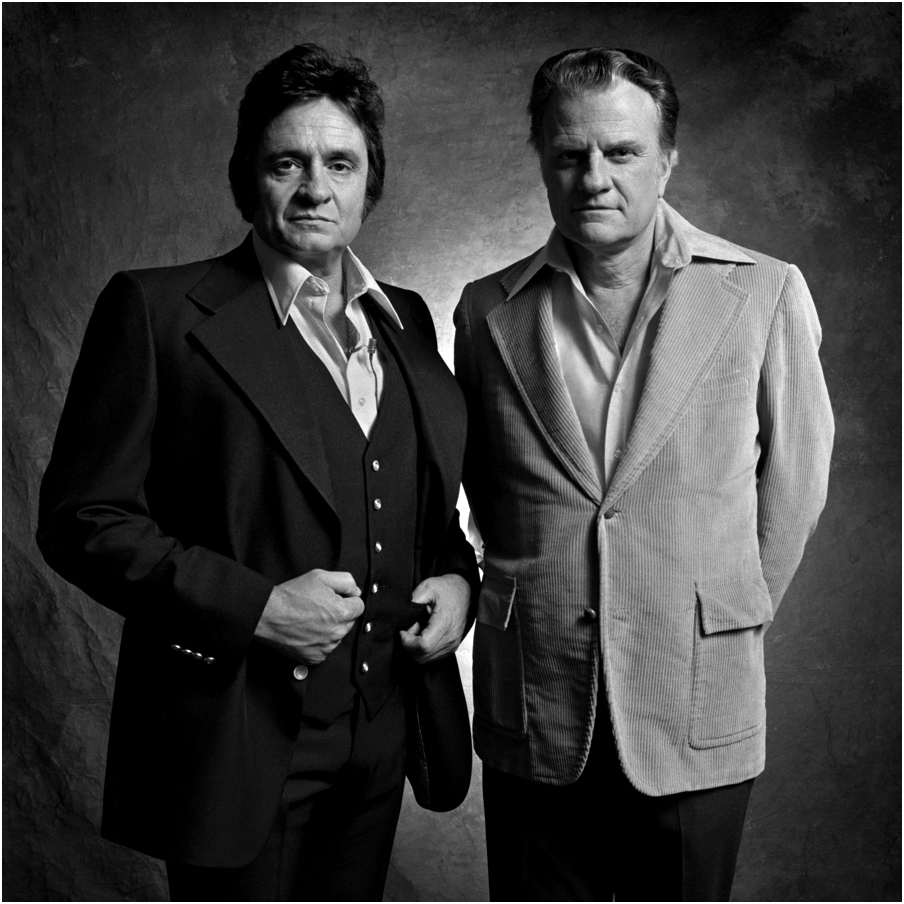

Johnny Cash and Billy Graham

A legacy of integrity

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, which would grow to become a well-oiled organization, was born in 1950.

Graham and his inner circle decided early on that they needed to find ways to steer clear of the scandals that had undone other preachers. So in 1948, they began crafting guidelines to live and preach by during a meeting in Modesto, Calif.

Among the pillars of this “Modesto Manifesto”: Set up an independent board to handle the money and never be alone with a woman other than their wives.

By all accounts, Graham and the others stuck by these commandments – Graham even had hotel rooms checked before entering them – and steered clear of the sex and money scandals that would later ruin such televangelists as Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart.

To Randall Balmer, a professor of religious history at Dartmouth College, it’s this integrity that was Graham’s greatest legacy.

“He was in the public eye for well over a half-century,” Balmer said, “and nobody ever leveled serious charges of scandal against him.”

Political lessons

But Graham’s friendships with Presidents Johnson and Nixon in the 1960s and ’70s brought him criticism, with some dismissing the North Carolinian as a preacher for the powerful.

“If he (had) a failing, it was precisely that: He was drawn to power like a moth to a flame,” said Balmer, author of “God in the White House.”

He grew close to Johnson, a Democrat and fellow Southern farm boy, and offered strong support for LBJ’s increasingly divisive war in Vietnam.

But “perhaps the most controversial period in Graham’s career,” said Steven P. Miller, author of “Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South,” came with the election of Johnson’s GOP successor. “It’s his relationship with Nixon that still lingers in many memories.”

Republican Nixon, too, courted Graham. In 1970, at the height of protests against Nixon and the Vietnam War, the president appeared with Graham at a crusade in Knoxville. It was a move, Nixon adviser Charles Colson later said, “to get some of Graham’s charisma to rub off on us.” Graham privately offered to aid Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign. And he stood by the embattled president during the worst days of Watergate.

When finally confronted with the transcripts of the Watergate tapes, with Nixon engaging not only in a coverup but in crude racial and religious stereotyping, Graham recoiled. “I was sick,” he said later. “It was a Nixon I didn’t know.”

From then on, Graham swore he’d never again throw partisan support to presidents or White House candidates.

Onto the international stage

For decades, Graham had had a yearning to preach the Bible in the Soviet Union and other countries under communist rule. And in 1977, Graham went to Hungary. In 1982, he accepted an invitation to go to Moscow for a “peace conference” approved by the Communist Party.

Graham’s connection to believers behind the Iron Curtain – some of whom ran to the altar when he gave the call – drew criticism from some of his longtime supporters. But Graham would later get some of the credit when Russians, Poles, and others rose up to end communism.

Over time, Graham’s travels and contacts also led him to temper his fire-and-brimstone religiosity and reach out to those in other religions, including Catholics.

“A lot of people saw Graham, but he also saw a lot of people,” said Grant Wacker, professor of Christian history at Duke University and author of “America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation,” a cultural biography. “His core beliefs stayed the same, but … he changed, got more progressive.”

For his 417th – and final – crusade, Graham, 86, returned to New York City in 2005. His last message was about the love of God – the only balm, he said, for those who feel hurt.

“Your Holy Father hasn’t abandoned you,” Graham said, his voice weakened by age and illness, “and he never will.”

As Graham slowed down, he battled various ailments, including symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, and his family became paramount. In 1995, he turned over the reins of the BGEA to son Franklin.

For his father’s 95th birthday party in November 2013, Franklin awarded prominent seats and roles in the program to Sarah Palin, Fox News personalities – and future President Donald Trump.

President Reagan Nancy Reagan and Billy Graham at the National Prayer Breakfast held at the Washington Hilton Hotel Feb. 5, 1981.

Influence, humility to the end

Americans never tired of Graham and came to expect his soothing words in times of national crisis. After the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, it was the white-haired Graham who gave the sermon at National Cathedral in Washington.

And scholars, whatever their criticisms of Graham, agree he had a profound, even historical, impact on religion and culture.

“He formed a towering redwood on the American religious landscape,” Wacker said. “We’ll hear the echoes of his ministering for generations.”

Beyond organizing crusades, Graham helped create today’s thriving evangelical Christian culture by birthing magazines (Christianity Today), co-founding seminaries (Gordon-Conwell) and calling international conferences to encourage grass-roots preachers (like the one in 1974 in Lausanne, Switzerland).

Biographer Martin called Graham “one of the most influential religious figures of the 20th century – there’s Billy, a couple of popes and Martin Luther King. It’s a short list.”

And Bill Leonard, former dean of the divinity school at Wake Forest University, goes even further: “the most enduring public evangelist in American history.”

But what was it about Graham that made him such an icon?

Not the profundity of his sermons, Graham watchers say. He wasn’t a religion scholar or a theologian.

Rather, he was an evangelist who was able to nimbly navigate the modern American cultural landscape. He preached to everybody from presidents to construction workers, golfed with Bob Hope, bantered with Woody Allen and Johnny Carson on TV, and – in 1989 – became the first member of the clergy to get a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

Graham the personality exuded humility and sincerity and found new ways to connect with everyday people in language they understood.

“That was his genius,” Balmer said. “He was (modern) America’s first religious celebrity.”

Others, though, say Graham’s greatness was that he let God use him.

“People don’t ponder his sermons,” Campolo once said. “But when he gets up there, you sense a power go over the congregation in the stadium.”

And yet, said Richard Land, president of Southern Evangelical Seminary in Matthews, Graham never took credit for that power or let it go to his head:

“I think he’s the one man who could endure the amount of adulation that he has received and still say honestly and sincerely, ‘Why me?’ ” Land said. “It is his impenetrable humility that made it so that God could use him.”

Graham’s view?

“I have been asked: ‘What is the secret?’ ” Graham told interviewers. “ ‘Is it showmanship, organization or what?’

“The secret of my work is God. I would be nothing without him.”

But why had God chosen him, a farm boy from Charlotte?

Graham’s answer: “That’s one of the questions I’ll ask the Lord when I see him.”

FORMER OBSERVER RELIGION EDITOR KEN GARFIELD CONTRIBUTED.