From Hegel to Woodrow Wilson, its philosophy has always led to the dehumanization of others.

December 5, 2018

Woodrow Wilson

Toward what do the progressives of today believe they are progressing? The chances are more than good that they have no idea. Somehow “progress” means greater equality, greater understanding, greater tolerance, greater peace, and greater evolution. Somehow. But it’s never entirely clear how. In almost every sense, modern progressives mean that anything they deem good is progressive while all else is not just wrong but evil.

Is there an actual end to the progress of progressives? Is there a threshold of equality that must be crossed, one that would at least allow us to claim victory? Is there some utopia just around the corner, achievable in some viable way?

I will not walk with your progressive apes,

Erect and sapient. Before them gapes

The dark abyss to which their progress tends—

If by God’s mercy progress ever ends,

And does not ceaselessly revolve the same

Unfruitful course with changing of a name

— J.R.R. Tolkien, “Mythopoeia”

Just as the progressives of today have no real sense of where their progress might or should lead, they have even less sense of their origins. Progressivism, as understood in the last several centuries, originated in the thought of the Prussian philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) and his contemporary Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814). As with all Prussians and most philosophers, Hegel’s and Fichte’s thoughts were complex and varied, not easily reduced to a quick soundbite or even a few sentences. Still, the progressive understanding of them is surprisingly simple. Drawing their own ideas from—and frankly distorting—the ancient wisdom of Heraclitus, the two Prussians believed that life moves forward through the struggles of societal forces. The forces that dominate most aspects of society, Fichte labeled the “thesis.” Those who opposed those forces, he called the “antithesis.” In their struggle—through and by which neither would wholly win—emerged a third thing, the “synthesis.” The synthesis, once arrived at, quickly became the thesis, opposed by a new antithesis. And the cycle started all over. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

This cycle of thesis-antithesis-synthesis was given the shorthand of “progress” and its advocates “progressives,” and it quickly dominated Germanic thought in the 19th century. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels especially coopted the idea.

Two things, however, must be noted. First, Progressivism very well might not have succeeded without the scientific idea of evolution re-emerging in the 1840s and 1850s. Darwinian evolution weaponized “progress,” giving it something quantifiable and endowing it with a staying power (one is tempted to write “endowing it with virtue,” if it were not such a perversion of virtue) that remains as strong to this day.

Second, whatever the intentions of Marx and Engels, the Left never had a monopoly on Progressivism. As the Germans adopted the idea early in the 19th century, the Anglo-American world did so with equal enthusiasm in the 20th century. Progressivism is really, at heart, pre- and trans-political. It is a theory of history and anthropology, not of politics. Deeply conservative men such as Harvard University’s Frederick Jackson Turner embraced the progressive vision of history. Whenever I teach students its meaning, I find they learn best by looking at the simplified version offered by Turner. “In this advance, the frontier is the outer edge of the wave—the meeting point between savagery and civilization,” Turner wrote in 1893. Then in rather poetic language evocative of every great western to be written for the silver screen during the following century, Turner explained:

This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character. The true point of view in the history of this nation is not the Atlantic coast, it is the great West.

In Turner’s progressive history, Europe serves as the thesis, Indians as antithesis, and Americans as the synthesis.

One need not limit this analysis to the 19th century. Modern neoconservatives such as Francis Fukyama have embraced the progressive vision of history just as readily as had Marx and Turner. Progressives have come to dominate academia, churches, the media, and especially politics. Woodrow Wilson might have been America’s most left-wing progressive president, but his ideas were not significantly different from those of either George Bush, not only in foreign policy but domestic policy. Both the Americans with Disabilities Act and the No Child Left Behind scream progressive, each placing what should have been dealt with privately and locally in the hands of Washington bureaucrats.

Yet even the most objective view of the progressive vision of history should give any intelligent and humane person pause. First, the progressive vision demands conflict. That is, in its understanding, history is made up of winners and losers. This flies directly against the long tradition of republican and Judeo-Christian thought that calls for the “common good” of the res publica, not the greater good of those who might be victorious. In the greater part of the Western tradition, at least up through the writings of Nicolo Machiavelli, the most important intellects recognized the flaws or fallenness of man, noting that power must be divided and guarded against. The progressives, wittingly or not, embraced the idea that those with established power should be taken down by others with power, thus creating a third and new power, itself soon to be the establishment and challenged. As such, the guiding force of society is might, not justice. In the res publica, ideally, each gives up some of his rights and treasure for the benefit of the whole. Thus, while each suffers some, the whole benefits mightily. No such rules or restraints govern the progressive vision. Truly it is a comparative: the greater good, not the common good. Power thus replaces love.

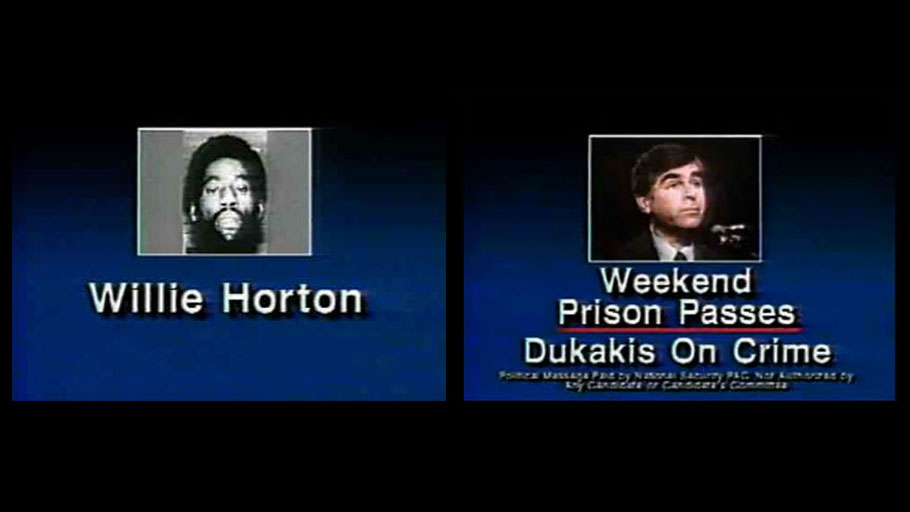

A second problem, very much related to the first, is that the progressive vision of history demands a victim. In the Marxian vision, it is the class enjoying dominance. One should not, therefore, be surprised to see mobs of Soviets dismantling mansions and executing the inhabitants. Even in the gentle vision of Turner, one readily sees how the Indians serve only one purpose in history: to turn Europeans into Americans. It’s as though generations and generations and generations of Indians existed only to give purpose and meaning to the European invaders. One can see what Gary Larson would do with this: a multitude of bored Indians hanging around Plymouth Rock, eagerly awaiting the coming of the Year of Our Lord 1620. One can see too how the murder of America’s original inhabitants could be easily justified.

As it happened, America’s first active progressives emerged from the annual Lake Mohonk conferences, sponsored by the “Friends of the Indian.” These do-gooders—almost all the children of evangelical ministers and almost none of whom had ever met an actual American Indian—believed in true progressive fashion that they knew how to make the Indians into “humans.” Their stated goal was horrific: “to kill the Indian to save the man.” Such friends one should avoid! They supported the reservation policies, the often forced Christianization of Indians, and the willful theft of Indian children from their biological parents. These latter they would send to East Coast boarding and trade schools, forcing them to “Americanize.” The most infamous of these schools was Carlisle Industrial, its cemetery full of the suicides of Indians who had been made to live neither in the world of their parents nor the world of their captors and who had escaped both only through death.

The progressives did not just target American Indians though. They also hated (and that word is not too strong) black Americans, Jewish Americans, and Catholic Americans. As Woodrow Wilson’s supporters put it, they wanted to “yank the hyphen” out of hyphenated Americans. He called the hyphen a dagger, ever ready to be wielded against the nation. Should it surprise anyone, therefore, that President Wilson not only segregated the U.S. Navy (it had always been desegregated, even in colonial days), but that he also segregated all federal offices and bureaucracies in Washington, D.C.?

Tellingly, it is impossible to separate Progressivism from racial and religious bigotry, especially in the United States. Eugenics and social engineering come directly from America’s progressives, who firmly believed in a lily white, Protestant America. One of progressivism’s most famous scholars—a man who supported and received the support of Teddy Roosevelt as well as Woodrow Wilson—was Edward Alsworth Ross, author of the wretched The Old World in the New (1914). “In this sense it is fair to say that the blood now being injected into the veins of our people is ‘sub–common,’” Ross asserted. “To one accustomed to the aspect of the normal American population, the Caliban type shows up with a frequency that is startling.” After analyzing the faults of each immigrant type—from Scandinavian to Sicilian to Jew—he lamented:

The overlooked that this man will beget children in his image—two or three times as many as the American—and that these children will in turn beget children. They chuckle at having opened an inexhaustible store of cheap tools and, Lo! the American people is being altered for all time by these tools. Once before, captains of industry took a hand in making this people. Colonial planters imported Africans to hoe in the sun, to “develop” the tobacco, indigo, and rice plantations. Then, as now, business minded men met with contempt the protests of the few idealists against their way of quote “building of the country.” Motors of prosperity are dust, but they bequeathed a situation which in four years wiped out more wealth than 200 years of slavery had built off, and which presents today the one unsolvable problem in this country. Without likening immigrants to Negroes, one may point out how the latter-day employer resembles the old-time planter in his blindness to the facts of his labor policy upon the blood of the nation.

As disturbing as Ross’s views are, they are the essential beginning of Progressivism. From its beginning, whether intentional or not, Progressivism has been racist and bigoted. Yet such results are true to its theory. If all history comes from conflicts over power, the losers will always be dehumanized. Crazily enough, the modern progressives have done the same thing, yet whereas once our history was written by the victors, it is now written by the victims. Neither is healthy for a stable, just, and free social order.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative