"Government is not reason; it is not eloquent; it is force. Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master." - George Washington

Saturday, July 20, 2019

The Lost Frontier

By Mark Steyn

July 20, 2019

Neil Armstrong

Fifty years ago today man landed on the moon, in the persons of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin and courtesy of a lunar module from Apollo 11. The most I've ever written about the "space race" was in my book After America, and the passage attracts criticism both from the Nasa types and those who think the whole man-on-the-moon thing was a crashing bore. Nevertheless, the modern world was built by the men who ventured beyond the edge of the map, and in that sense the stasis of the last half-century is both unusual and a little disturbing. To mark the anniversary, The New York Times wondered when a woman might reach the moon - which sounds a humorless rewrite of the old feminist gag that "if they can put a man on the moon, why can't they put them all there?" So here's a few of my thoughts on the subject over the years:

The Wright brothers' first flight was in 1903. Fifty-nine years later, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth, and seven years after that Buzz Aldrin became the first man to fly to the moon and play "Fly Me To The Moon" on the moon - thanks to the portable cassette recorder he took with him. In a certain sense, the moon landing was the culmination of the tremendous inventive energy of the nineteenth century (if I had to pick a so-called "greatest generation" it would be somewhere in the latter half thereof). Half a century from the Wright Brothers to The Right Stuff - from nosediving into the neighbor's cornfield to walking the surface of the moon - followed by half a century devoid of giant leaps and even small steps.

When After America came out, I was booked on "Fox & Friends" to talk it over with Brian Kilmeade. Sitting next to Brian on the couch waiting to get going, I watched Steve Doocy across the studio link to an item on the space shuttle Enterprise beginning its journey to whichever museum it's wound up at. Steve called it "historic", and, as I remarked to Brian, pity the nation whose greatness becomes "historic" - whose spacecraft exist only in museums. There's a passage in After America on just that theme:

In 1961, before the eyes of the world, President Kennedy had set American ingenuity a very specific challenge—and put a clock on it:

'This nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.'

That's it. No wiggle room. A monkey on the moon wouldn't count, nor an unmanned drone, nor a dune buggy that can't take off again but transmits grainy footage back to Houston as it rusts up in the crater it came to rest in. The only way to win the bet is with a real-live actual American standing on the surface of the moon planting the Stars and Stripes. Even as it happened, the White House was so cautious that William Safire wrote President Nixon a speech to be delivered in the event of disaster:

'Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace...'

Yet America did it.

It was not a sure thing. In 1961 the Soviets had it all over the Americans in the space race: They had already reached the moon, with the unmanned flight Luna 2, and they had put a man in space, Yuri Gagarin. Gagarin and the cosmonauts were inspirational figures well beyond the Warsaw Pact. By contrast, all the US unmanned missions had been failures, and their astronauts were earthbound - or sub-orbital at best. Kennedy was cautioned against his moon speech on the grounds that he was setting America up for very public humiliation.

But he chose to go ahead.

And now? From After America:

Four decades later, Bruce Charlton, professor of Theoretical Medicine at the University of Buckingham in England, wrote that "that landing of men on the moon and bringing them back alive was the supreme achieve- ment of human capability, the most difficult problem ever solved by humans." That's a good way to look at it: the political class presented the boffins with a highly difficult and specific problem, and they solved it—in eight years. Charlton continued:

'Forty years ago, we could do it—repeatedly—but since then we have not been to the moon, and I suggest the real reason we have not been to the moon since 1972 is that we cannot any longer do it. Humans have lost the capability.'Of course, the standard line is that humans stopped going to the moon only because we no longer wanted to go to the moon, or could not afford to, or something.... But I am suggesting that all this is BS. . . . I suspect that human capability reached its peak or plateau around 1965-75—at the time of the Apollo moon landings—and has been declining ever since.'

Can that be true? Charlton is a controversialist gadfly in British academe, but, comparing 1950 to the early twenty-first century, our time traveler from 1890 might well agree with him. And, if you think about it, isn't it kind of hard even to imagine America pulling off a moon mission now? The countdown, the takeoff, a camera transmitting real-time footage of a young American standing in a dusty crater beyond our planet blasting out from his iPod Lady Gaga and the Black-Eyed Peas or whatever the twenty- first-century version of Sinatra and the Basie band is. ... It half-lingers in collective consciousness as a memory of faded grandeur, the way a nineteenth-century date farmer in Nasiriyah might be dimly aware that the Great Ziggurat of Ur used to be around here someplace.

How long will it even half-linger? Great civilizations can survive a lot of things, but not impoverishment of spirit. That's one reason I didn't join in the media sniggers at Donald Trump's new Space Force - because I'd like it to be true. Here's me and Michio Kaku taking it seriously:

As I commented a year or so back:

Those "Space Age" astronauts were men of boundless courage and determination: they strapped themselves in and stared not just death in the face but death in hideous and unknown ways. Yet they were also ordinary men, who were called upon to do extraordinary things and rose to the challenge. These days we are unmanned in more than merely the sense of that Luna 2 expedition. Glenn and Armstrong are gone, and their surviving comrades are old and stooped and wizened, and yet the only giants we have. Space may still be the final frontier, but today, when we talk about boldly going where no man has gone before, we mean the ladies' bathroom. Progress.

~adapted from Mark's bestseller After America. Personally autographed copies areexclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

As the third year of The Mark Steyn Club cranks into top gear, we're very appreciative of all those who signed up in our first flush and have been so eager to re-re-subscribe for another twelve months. We thank you all, and hope to see at least a few of you to thank you personally on our Second or Third Steyn Cruise. For more information on the Club, see here.

The Apollo 11 Moon Landing Was A Triumph Of American Exceptionalism

By Joshua Lawson

https://thefederalist.com/2019/07/18/apollo-11-moon-landing-triumph-american-exceptionalism/

July 18, 2019

Edwin Aldrin poses for a photo beside the U.S. flag on the moon (July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong)

In the 2008 space documentary “When We Left Earth,” while addressing the success of the Apollo 11 moon landing, Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders remarked that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were “humans” who “just happened to be Americans.”

Last year, Canadian actor Ryan Gosling played Neil Armstrong in Damien Chazell’s biopic “First Man.” In an echo of Anders’s comments from a decade earlier, Gosling raised the eyebrows of many Americans when he said the moon landing was “widely regarded in the end as a human achievement” and that’s how the team making “First Man” chose to view it.

These statements are part of a trend of historical revisionism that paints every American achievement as universal and global while portraying the nation’s past sins as exclusively American. In truth, NASA’s missions in general—and the Apollo 11 moon landing in particular—represent an odds-defying triumph of American exceptionalism.

The NASA Missions Awoke America’s Competitive Spirit

Like many of the most inspiring adventures in history, the American moon landing is a comeback story. The United States began the space race trailing the Soviet Union. In 1957, the U.S.S.R. stunned the world when they successfully launched the Sputnik satellite into orbit. The first man in space was not an American but Soviet Yuri Gagarin.

Those involved in the first days of NASA were flabbergasted at the early Soviet success. Space correspondent Jay Barbree recalls the sentiment of the time: “These people couldn’t build a refrigerator…how can they get into orbit?”

Rather than looking at the initial score in the space race and giving up, Americans saw the deficit they had to overcome and were emboldened. The Soviets touched a nerve. Unknowingly, they reinvigorated the determined, persevering, and rugged streak embodied in the very nature of the United States. In the drive to remain the preeminent leader in science and engineering, the NASA missions tapped into something deep within the American character.

The space program that led to men landing on the surface of the moon is part of the grand narrative of Americans braving forth and conquering the unknown. The Apollo program and the Mercury and Gemini missions that preceded them were victories of innovation, adaptation, and a hungry (and distinctively American) competitive instinct. Although there were certainly some non-American-born engineers and scientists working for NASA in the 1960s, the entire endeavor was fundamentally American in its ethos.

Americans Have Never Been Afraid of Challenges

When remembering the role of President John F. Kennedy in imploring Americans to reach for the stars, most remember his famous “moonshot” challenge to a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961. More revealing, however, is Kennedy’s underappreciated Rice University speech in September 1962. Kennedy spoke about one of the core aspects of America’s spirit:

This city of Houston, this State of Texas, this country of the United States was not built by those who waited and rested and wished to look behind them. This country was conquered by those who moved forward…

As Edward R. Morrow had reminded the nation eight years earlier, if you dig into the nation’s history, you will find that Americans are not descended from fearful men. The pillar of American exceptionalism most relevant to the NASA missions is America’s embrace of competition and the fearless, enterprising spirit that accompanies it. The most famous line of Kennedy’s speech at Rice strikes at the heart of the matter:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard … [the] challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win…

As Kennedy explained, pursuing challenge head-on and accepting the hardships that come with exploring new frontiers was part of the American ethos well more than a century before the nation’s founding. Writing on his establishment of America’s first successful colony in New England, Plymouth governor William Bradford remarked:

…all great and honourable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and must be both enterprised and overcome with answerable courages…all of them, through the help of God, by fortitude and patience, might either be borne, or overcome.

Plymouth has been called “America’s hometown,” a moniker it deserves in more ways than one. Not just the site of the first Thanksgiving, Plymouth, like the Apollo program, had a history of early struggles. The challenges of founding and sustaining the burgeoning New England settlement were met directly—even embraced. So it was with the moon landing.

The Old West Forged the Keys to Win the Space Race

Kennedy was on to something when he harnessed the idea of a “New Frontier” during the 1960 presidential election race. After the U.S. Census of 1890 reported the closing of the American frontier in the West, historian Frederick Jackson Turner revealed that much of what made America so exceptional and successful could be tied to the exploration of its expansive frontier.

This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities … furnish the forces dominating American character. … At the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish. …Early Western man was an idealist withal. He dreamed dreams and beheld visions. He had faith in man, hope for democracy, belief in America’s destiny, unbounded confidence in his ability to make his dreams come true.

In the roughest days of the American West, the harsh, unforgiving, and trying experience of trying to eke out a living was a baptism of fire. The nation’s character was both forged and revealed in the conditions of the Old West.

Turner observed that America owes its most striking attributes to the frontier. It took a particular brand of dogged determinism to fight against the unforgiving climate, an often-hostile native population, and the ever-present threat of failure.

That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism … withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier.

These were the perfect combination of civilizational traits needed to win the space race. The characteristics required to land men on the moon and return them safely to earth were fostered in the West and ingrained in the culture of the United States.

Apollo 11 Flight Director Gene Kranz recalls how the early days of NASA were like “learning to drink from a fire hose.” Kranz and his entire team had to learn about trajectories, orbits, and “retrofire” essentially from scratch. “We had to virtually invent or adapt every tool that we used,” he says.

When NASA began project Mercury in 1958, they were driving blindly into the dark. Yet Kranz had confidence in his team. “We had the knowledge, the moxie, and the will to not only catch up but surpass at beat them [the Soviets] in the business of space flight.” Fifty years ago, on July 20, 1969, that victory was cemented in the annals of history.

America Cannot Afford a Lack of Pioneers and Explorers

Besides the American astronauts who took part in the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions, at the peak of the Apollo program, NASA employed more than 400,000 American men and women.

Not to be forgotten are the three Americans who gave their lives in the pursuit of the dream of putting a man on the moon. Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee perished in a tragic fire during the Apollo 1 mission, marking the first fatalities suffered by NASA, and sadly, were not the last. President Ronald Reagan reminded the nation after the Challenger disaster in 1986, “The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave.”

As NASA and American private enterprise work together to return Americans to the moon, and then onward to Mars and beyond, we would do well to recall and pay tribute to the American spirit that got us to the moon 50 years ago. The challenge of discovery, the conquest of the unknown, and a thirst for adventure are part of the American ethos.

America is at its best when it embraces the pioneering ideals revealed by Bradford and Turner and articulated so movingly by President Kennedy. When John Glenn returned to earth after becoming the first American in orbit, Kennedy described space as “the new ocean,” remarking that the United States should “sail on it and be in a position second to none.”

The far reaches of space remain an uncharted frontier of limitless potential. As the world’s most indispensable and exceptional nation, America must always be ready to venture forward and explore what lays beyond the next horizon.

Joshua Lawson is a graduate student at the Van Andel School of Statesmanship at Hillsdale College. He is pursuing a masters degree in American politics and political philosophy.

New York Times Goes Pro-Soviet for Moon Landing Anniversary

BY ROGER L. SIMON

https://pjmedia.com/rogerlsimon/ny-times-goes-pro-soviet-for-moon-landing-anniversary/

July 19, 2019

Soviet tanks roll through the streets of Budapest in 1956.

The New York Times — that Democratic Party house organ that fancies itself "liberal" or "progressive" or some such — is actually one of the more reactionary institutions in our country. Sometimes you have to wonder if it might actually be an American version of Izvestia.

Speaking of which, in honor of the fifty-year anniversary of the USA putting a man on the moon, the once-upon-a-time newspaper of record produced this ridiculous nonsense under the rubric "How the Soviets Won the Space Race for Equality."

The Cold War was fought as much on an ideological front as a military one, and the Soviet Union often emphasized the sexism and racism of its capitalist opponents — particularly the segregated United States. And the space race was a prime opportunity to signal the U.S.S.R.’s commitment to equality. After putting the first man in space in 1961, the Soviets went on to send the first woman, the first Asian man, and the first black man into orbit — all years before the Americans would follow suit.

How PC.

The author, Sophie Pinkham, a doctoral candidate in Slavic Languages, would have to know what these enlightened "multi-culti" Soviets did, in the interest of "equality," just a scant year before the U.S. landed on the moon — invade Czechoslovakia, crushing "Prague Spring."

Oh, but they were putting a woman in space so it was all good. And after all, "Prague Spring" wasn't all that great. It was led by a (gasp!) white male — Alexander Dubcek. The brutal annihilation of the Czech's (naively idealistic but sweet — in retrospect) "socialism with a human face" occurred after the Soviets had done virtually the same thing to Hungary in 1956, a scant twelve years before. You may have seen the photos of the tanks sweeping through Budapest.

Nostalgia for the Soviet Union in any form is dangerous and massively self-indulgent, yet Ms. Pinkham seems to have some peculiar desire to be even-handed, i. e. to see the good side of evil. Perhaps she sees it as fodder for her thesis. She also wrote, "Cosmonaut diversity was key for the Soviet message to the rest of the globe: Under socialism, a person of even the humblest origins could make it all the way up."

Ah, diversity — the new religion. As long as they can put a "person of color" — also, of course, mentioned in the article — or from the proletariat in space, everything else is excused.

Even the Gulag Archipelago. Even the Purge Trials. Even Beria. Even the Plot Against the Doctors. Even Stalin's mass starvation of millions of Ukrainians known as the Holodomor. Even the incarceration of Sakharov and the Refuseniks that was going on before, after, and during the cosmonaut program, etc., etc. (How was that last one in terms of "equality," Ms. Pinkham? As the author also no doubt knows, citizens of the Soviet Union had to carry internal passports identifying their "nationalities" as "Jews," "Tatars," etc. It was the very opposite of equality. It was ethnic and racial stereotyping for totalitarian purposes.)

This whitewashing of the Soviet Union has been a standby of the New York Times almost since Lenin arrived at the Finland Station. The whitewashing reached a fever pitch during that very Holodomor (early 1930s) when Walter Duranty — the paper's Moscow correspondent and perhaps history's all-time greatest perpetrator of fake news — deliberately lied on the newspaper's front page about the extent of the devastation in Ukraine (millions dying) in order to remain in Stalin's good graces.

Duranty won a Pulitzer for his coverage. His photograph still hangs on the wall in the Times building with all the paper's other honorees, in case anyone wants to go and throw up. Ms. Pinkham is unlikely to win a Pulitzer for her space coverage. But she is carrying on a putrid tradition.

Roger L. Simon — co-founder and CEO emeritus of PJ Media — is an award-winning author and an Academy Award-nominated screenwriter. His new novel — THE GOAT — will be out in September.

Thursday, July 18, 2019

Authors Who Shaped Me

By Bradley J. Birzer

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/07/authors-shaped-me-bradley-birzer.html

July 15, 2019

'The Bookworm' by Carl Spitzweg (1850)

Ever since attending first grade—at Wiley Elementary School in Hutchinson, Kansas—I’ve loved to read. I can still see that very first book I checked out from the school library (then, a detached trailer sitting in the school playground), an orangish-red hardback biography of Lewis and Clark. From there, I read about Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and other great patriots of the founding era; I read about fantastic creatures; I read about UFOs, Atlantis, and the occult; and I read just about every mystery written for kids.

It was between 1979, sixth grade, and 1982, ninth grade, that I began to read according to author, rather than according to subject. It was during those years that my adult tastes began, shaping my thoughts (such as they were) as well as my aspirations. During those years, aside from my lawn-mowing business, I spent my free time divided between two activities—exploring the environs in and around Hutchinson (from oil derricks to wheat fields to abandoned buildings) and reading everything under the sun.

The first great author that meant something to me was Ray Bradbury. Sometime in fifth grade, I picked up a copy of The Illustrated Man and The October Country. I kept each by my bedside, reading one or two stories a night. The mystery of each story spoke to me, but so did Bradbury’s language. Even then I recognized that he wrote in ways superior to most other authors. I found myself enjoying his tales of dark imagination but immersing myself completely in his vocabulary and writing structure. Soon, I was reading everything I could find by Bradbury, but I was especially taken with The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451.

The second great, J.R.R. Tolkien, arrived in my life during the third week of September 1977. My oldest brother, Kevin, was turning 18, and my mother gave him a just-then published copy ofThe Silmarillion. Though I did not understand it all, I read that opening—the creation story—repeatedly over the next several years. To this day, I can’t read Genesis 1 without Tolkien’s imagery dominating my imagination. Two summers later, I devoured The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Throughout 1979 through 1980, I read just about every science-fiction and fantasy author available to me, but Bradbury and Tolkien had given me a taste of the best, and I found myself reading George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984. Having recently re-read 1984, I found the novel shockingly sexual, something I missed back in junior high on my first reading. Then, it was the repression, the resistance, and the rats that most affected me.

From my first books, my mom had ably guided and encouraged my reading. From time to time, she would simply hand me books and tell me it was time for me to read them. Usually, these became profound moments in my life. I’ll never forget the first few pages of Mila 18 orExodus or Armageddon by Leon Uris. As with Orwell, with Uris I began to identify more and more with the oppressed. Of course, in hindsight, I see I was doing that back to my very first readings of the children’s biographies of the American patriots. I also began to see wide sweeps of history, cultures, and religions.

At the very end of seventh grade—in May 1981—I saw Ronald Reagan speak at the University of Notre Dame, and political awareness entered my life for the first time. It was an utterly profound moment for me, and I fell in love with our fortieth president. Having grown up in a Goldwater household, I was already primed, but it was that speech at Notre Dame that meant everything to me. One of the many political books lying around the house—Robert J. Ringer’sRestoring the American Dream—caught my eye, and I came to cherish every word. As much as I would love to claim Tolkien and Bradbury as my primary inspirations to want to become an author, it was most certainly Ringer’s book, his arguments, and his writing style that shaped all my authorial hopes! I got so into Ringer that I became a rather obnoxious junior-high evangelist for the free society. Believe me, my classmates already thought I was odd. My new-found love only gave them greater evidence.

From Ringer, I rather naturally migrated to the words of Milton Friedman. No, I didn’t read hisMonetary History of the United States, but I read with relish Capitalism and Freedom, Free to Choose, and his numerous columns in Newsweek.

In the summer of 1982, between eighth and ninth grades, I began to prepare for high-school debate. Part of that preparation involved meeting the grand master of debate and economics, Greg Rehmke, who introduced me to the works of Henry Hazlitt.

Toward the end of that summer, I read (consumed and devoured would be more accurate descriptives) and analyzed every little detail of Economics in One Lesson and The Conquest of Poverty. Whatever one might think of Economics in One Lesson as an economic text (and, I don’t have the skills to judge it), it was an extraordinary lesson in basic logic. I had read and outlined it so many times that I had much of the book memorized in high school. Indeed, nothing shaped my own understanding of logic more than did Hazlitt and, not surprisingly, the Sherlock Holmes stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Yes, I loved those as well. The arguments I encountered in Hazlitt and Doyle gave me great confidence to express my views in high school classes as well as in college classes.

From biography to high fantasy to rigorous logic. If I can offer any advice regarding my own experiences, it is this: Don’t censor what your kids read, but do encourage them.

The War Over America’s Past Is Really About Its Future

By Victor Davis Hanson

https://townhall.com/columnists/victordavishanson/2019/07/18/the-war-over-americas-past-is-really-about-its-future-n2550201

July 17, 2019

The summer season has ripped off the thin scab that covered an American wound, revealing a festering disagreement about the nature and origins of the United States.

The San Francisco Board of Education recently voted to paint over, and thus destroy, a 1,600-square-foot mural of George Washington's life in San Francisco's George Washington High School.

Victor Arnautoff, a communist Russian-American artist and Stanford University art professor, had painted "Life of Washington" in 1936, commissioned by the New Deal's Works Progress Administration. A community task force appointed by the school district had recommended that the board address student and parent objections to the 83-year-old mural, which some viewed as racist for its depiction of black slaves and Native Americans.

Nike pitchman and former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick recently objected to the company's release of a special Fourth of July sneaker emblazoned with a 13-star Betsy Ross flag. The terrified Nike immediately pulled the shoe off the market.

The New York Times opinion team issued a Fourth of July video about "the myth of America as the greatest nation on earth." The Times' journalists conceded that the United States is "just OK."

During a recent speech to students at a Minnesota high school, Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) offered a scathing appraisal of her adopted country, which she depicted as a disappointment whose racism and inequality did not meet her expectations as an idealistic refugee. Omar's family had fled worn-torn Somalia and spent four years in a Kenyan refugee camp before reaching Minnesota, where Omar received a subsidized education and ended up a congresswoman.

The U.S. Women's National Soccer Team won the World Cup earlier this month. Team stalwart Megan Rapinoe refused to put her hand over heart during the playing of the national anthem, boasted that she would never visit the "f---ing White House" and, with others, nonchalantly let the American flag fall to the ground during the victory celebration.

The city council in St. Louis Park, a suburb of Minneapolis, voted to stop reciting the Pledge of Allegiance before its meeting on the rationale that it wished not to offend a "diverse community."

The list of these public pushbacks at traditional American patriotic customs and rituals could be multiplied. They follow the recent frequent toppling of statues of 19th-century American figures, many of them from the South, and the renaming of streets and buildings to blot out mention of famous men and women from the past now deemed illiberal enemies of the people.

Such theater is the street version of what candidates in the Democratic presidential primary have been saying for months. They want to disband border enforcement, issue blanket amnesties, demand reparations for descendants of slaves, issue formal apologies to groups perceived to be the subjects of discrimination, and rail against American unfairness, inequality, and a racist and sexist past.

In their radical progressive view — shared by billionaires from Silicon Valley, recent immigrants, and the new Democratic Party — America was flawed, perhaps fatally, at its origins. Things have not gotten much better in the country's subsequent 243 years, nor will they get any better — at least not until America as we know it is dismantled and replaced by a new nation predicated on race, class and gender identity-politics agendas.

In this view, an "OK" America is no better than other countries. As Barack Obama once bluntly put it, America is only exceptional in relative terms, given that citizens of Greece and the United Kingdom believe their own countries are just as exceptional. In other words, there is no absolute standard to judge a nation's excellence.

About half the country disagrees. It insists that America's sins, past and present, are those of mankind. But only in America were human failings constantly critiqued and addressed.

America does not have to be perfect to be good. As the world's wealthiest democracy, it certainly has given people from all over the world greater security and affluence than any other nation in history — with the largest economy, largest military, greatest energy production, and most top-ranked universities in the world.

America alone kept the postwar peace and still preserves free and safe global communications, travel and commerce.

The traditionalists see American history as a unique effort to overcome human weakness, bias, and sin. That effort is unmatched by other cultures and nations, and explains why millions of foreign nationals swarm into the United States, both legally and illegally.

These arguments over our past are really over the present — and especially the future.

If progressives and socialists can at last convince the American public that their country was always hopelessly flawed, they can gain the power to remake it based on their own interests. These elites see Americans not as unique individuals but as race, class and gender collectives, with shared grievances from the past that must be paid out in the present and the future.

We've seen something like this fight before, in 1861 — and it didn't end well.

Wednesday, July 17, 2019

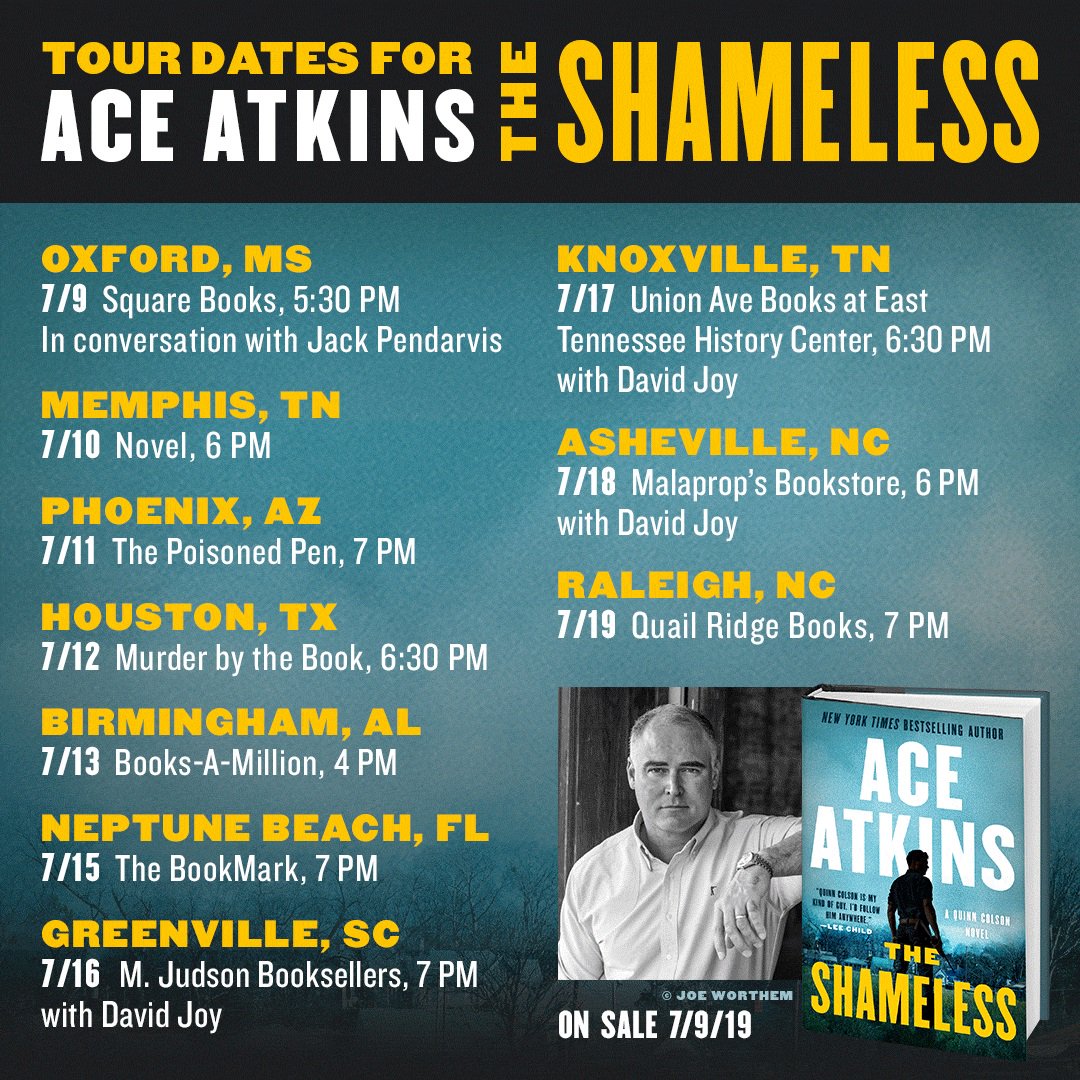

It’s tough to tell crime from politics in Ace Atkins’ ‘The Shameless’

By Collette Bancroft

https://www.tampabay.com/books/its-tough-to-tell-crime-from-politics-in-ace-atkins-the-shameless-20190712/

July 12, 2019

The title of Ace Atkins’ ninth novel about Mississippi Sheriff Quinn Colson is a tipoff that one of the book’s main subjects is politics: It’s called The Shameless.

Atkins, a former St. Petersburg Times and Tampa Tribune reporter, writes the Colson series as well as continuing the late Robert B. Parker’s Spenser series. (His eighth Spenser book, Angel Eyes, will be published in November.) Colson is a native of the fictional town of Jericho in Tibbehah County, Miss., a man with a deep knowledge of his state’s problems who refuses to surrender to them.

“He’d been sheriff now for nearly a decade and he still wasn’t sure the state was getting any better. It was the entire reason he’d retired early as a U.S. Army Ranger, believing he could make a difference, fighting corruption, drug running, and violence in his own backyard.”

As The Shameless opens, he’s feeling discouraged. With his new wife, Maggie, Quinn is making an obligatory appearance at the county fair, where the two hear a speech by a slick, silver-haired politician named Jimmy Vardaman, whom Quinn knows all too well.

“Vardaman,” Atkins writes, “had kept a big hunt lodge in Tibbehah County for decades, the source of wild rumor and sustained fact, a place where he’d worked out deals with some of the most corrupt sorry-ass people in north Mississippi. Several times Vardaman had been on the fringe of people Quinn had either sent to jail or shot. But Vardaman always slipped clear of it, like a man who stepped in cow s--- and came out smelling like Chanel No. 5.”

Now Vardaman is running for governor on a populist platform that stops just half a breath short of outright racism, spouting religious platitudes despite his skeevy past. The crowds love him.

Quinn and Maggie don’t, but when they leave partway through his speech they’re confronted by a clutch of black-clad thugs who tell Quinn he “ain’t got no right trying to make Senator Vardaman uncomfortable.”

“Quinn had met a hundred guys like this,” Atkins writes, “wannabe Special Forces operators who took online courses and drooled over gun magazines.” When one of them threatens Maggie, Quinn steps up. “Didn’t even drop your cigar,” she says admiringly.

Another of Vardaman’s devoted supporters in Jericho is a Bible-thumping county official known to all as Old Man Skinner. His current project is raising money to erect a 60-foot cross next to the highway, where it will obscure a “damn Mississippi landmark,” the big neon sign for a strip club called Vienna’s Place. It’s a classic situation — campaigning politicians raging righteously against the vice they happily indulge in once the votes are counted.

The club’s proprietor, the lovely and formidable Fannie Hathcock, has a more pressing problem: a turf battle she’s fighting against other Mississippi organized crime bosses, including a Tunica casino mogul and a Choctaw chief.

In the last Colson novel, The Sinners, one casualty of those turf wars was Quinn’s best friend and fellow vet, Boom Kimbrough, who is now struggling to recover from a savage beating. Quinn’s fierce former deputy, Lillie Virgil, now a U.S. Marshal, has made it her business to arrest a dirtbag named Wes Taggart, one of Boom’s attackers. (Quinn shot the other one.) She captures Taggart with the help of his ex-girlfriend, a high school senior turned stripper “whose real name was Tiffany Dement but went by Twilight to avoid professional confusion.” Taggart’s arrest, however, will trigger further chaos.

Meanwhile, Quinn’s sister Caddy, a recovering addict, is running her ministry for refugees and poor and homeless people on half a shoestring and trying to figure out why Bentley Vandeven, a rich kid from Memphis, is romancing her.

Into that mix of the usual homegrown characters Quinn deals with, Atkins tosses a couple of folks from the big city — Brooklyn, to be exact. Tashi Coleman and Jessica Torres are settling into Jericho to do research for their true-crime podcast, Thin Air. They’re digging into the disappearance 20 years ago of a local teenager, Brandon Taylor, who vanished while deer hunting. When he was found with a bullet through his head, his death was deemed a suicide, but his family doesn’t buy it.

It’s not just another cold case for Quinn. Brandon was a few years younger, but Quinn knew him in high school. And Brandon’s girlfriend then was Maggie Powers — now Quinn’s wife. Her young son, whom Quinn is about to adopt, is named after Brandon.

Tashi and Jessica are also chasing rumors that the former sheriff, Hamp Beckett, who was Quinn’s uncle, might have covered up the real nature of Brandon’s death.

That’s a lot of plot lines, but Atkins keeps them running smooth and hitting on all pistons as the action accelerates. Could Fannie’s power struggles and Caddy’s “Ole Miss frat boy” suitor and Brandon Taylor’s long-ago death and Vardaman’s current campaign all be related? You’ll be surprised.

Contact Colette Bancroft at cbancroft@tampabay.com or (727) 893-8435. Follow @colettemb.

The Shameless: A Quinn Colson Novel

By Ace Atkins

Putnam, 446 pages, $27

Meet the author

Ace Atkins will be a featured author at the Tampa Bay Times Festival of Reading on Nov. 9 at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg.

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

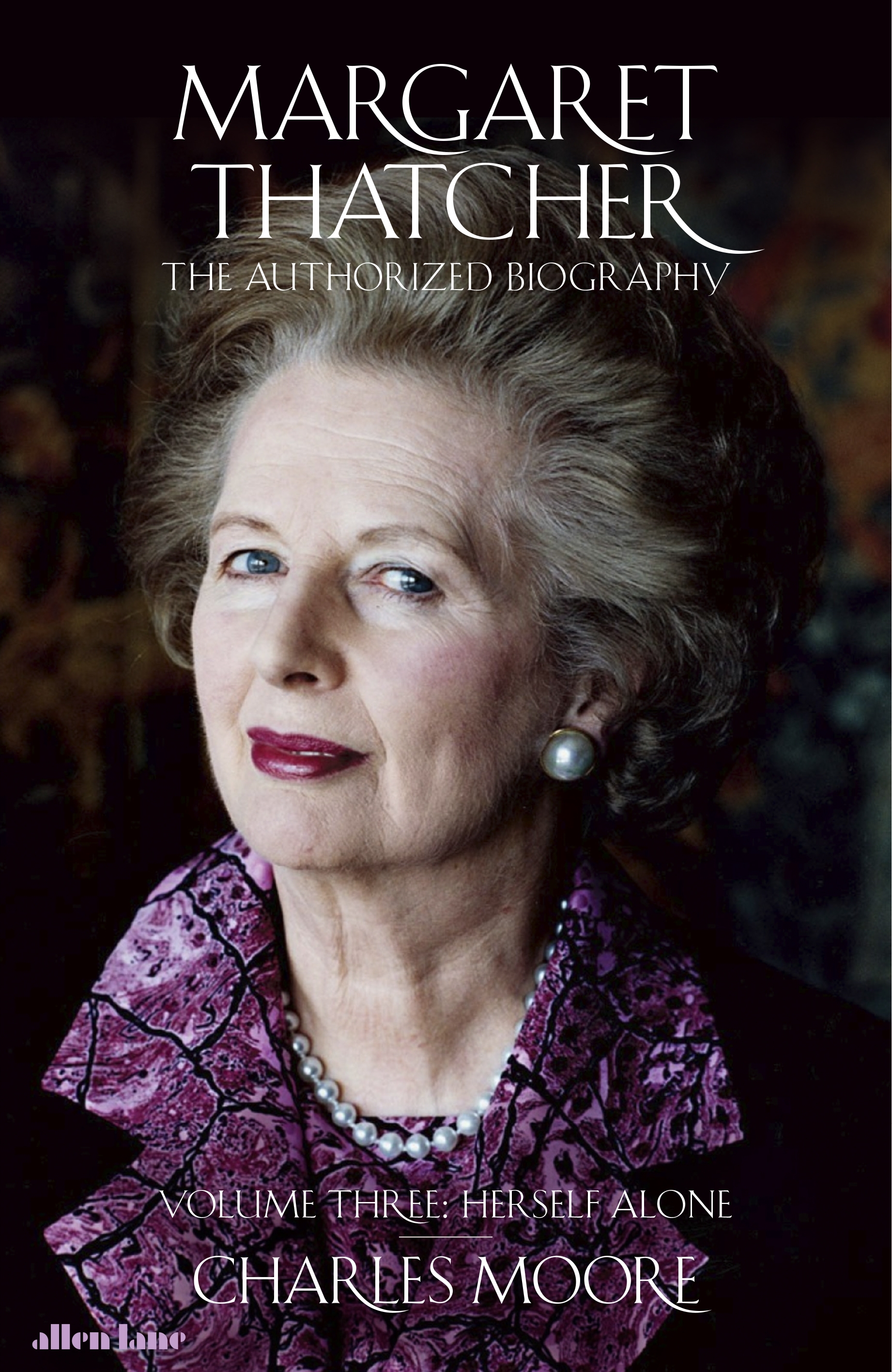

Thatcherism Without Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Three: Herself Alone, by Charles Moore (Allen Lane, 880 pp., $24.06)

Forty years on, Margaret Thatcher’s election as Great Britain’s first female prime minister still looks miraculous. The rise of a woman to dominance, in the hostile, closed environment of the British Conservative Party, was astounding. In The Iron Lady (2011), Meryl Streep makes the point eloquently. But the miracle that followed Thatcher’s election is no less remarkable.

Right after World War II, Labour prime minister Clement Attlee, overly optimistic about the capacity of government to do great things, laid the foundations of the British welfare state. The sentiment was understandable: centralized authority had just proved itself capable of organizing the country’s resources in the war effort. Well-meaning do-gooders now assumed that the state could do the same postwar, defeating the peacetime adversaries of poverty and need. Filmmaker Ken Loach calls this attitude “the spirit of ’45.” The postwar economic consensus was so robust that it became known as Butskellism, since the policies of Rab Butler, the Conservative chancellor of the Exchequer from 1951 to 1955, and his Labour predecessor Hugh Gaitskell were indistinguishable.

The glory days of interventionism didn’t last, however. By 1979, a third of the British workforce was employed by government, directly or indirectly, yet unemployment continued to rise throughout the 1970s. Inflation rose to double digits, exceeding 25 percent, making even middle-class Britons insecure about their savings and purchasing power. Keeping it under control seemed impossible: government-owned businesses, unable to say “no” to the demands of the trade unions, administered a vast portion of the economy.

Thatcher recognized the economic crisis as a failure of politics. She offered a gospel of government retrenchment and individual initiative that sounded outdated. She wanted to make people responsible again for their economic destinies, instead of entrusting their fates to state guidance. This meant denationalizing the British economy. Before Thatcher took office, “privatization” was a word out of science fiction; ten years after she left office, it was a global norm. She changed England and, by changing England, changed the world.

Thatcher was guided by ideology without being an ideologue, as the third and final volume of Charles Moore’s biography demonstrates. She compromised when needed and used her political compass to pick her fights. The British don’t like designating “isms” for their prime ministers. There was no “Gladstonism,” and “Churchillism” is a rare usage, but “Thatcherism” is the exception. In 1999’s The Anatomy of Thatcherism, Shirley Letwin emphasized that Thatcherism was less ideology than attitude—an understanding of society as the spontaneous development of individuals and families, who ought to be the subjects of their own fate and not the passive objects of national politics. Thatcher aimed to stimulate self-reliance and independence, and she saw these virtues threatened by the culture of passivity that statism engenders. Victorian values like thrift, prudence, and diligence, she once told historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, “were the values when our country became great.”

While Thatcherism is mostly associated with a set of policies (privatization, tax cuts, monetarism), it should be seen as part of a broader cultural picture. Thatcher’s agenda benefited from years of discrete and tireless cultural work, mostly by the Institute of Economic Affairs, the forerunner of modern, market-oriented think tanks. But her instincts were at least as important as her ideas. Alfred Sherman—indispensable as an early advisor and speechwriter but eventually excluded from her inner circle—once told me that Thatcher never read Friedrich Hayek or Milton Friedman, as she had claimed, but only Frederic Bastiat. Bastiat’s classic essay, “What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen,” with its emphasis on the long-term, unintended consequences that flow from apparently beneficial efforts, so that intended societal gains end up as losses, is perhaps the only economic lesson any prime minister needs to learn. That we shouldn’t clip the wings of those who will follow us down the road is perhaps the gist of Thatcherism, with its call to responsibility in the public sphere to allow for liberty in the private one.

Thatcher embodied the highest qualities of leadership. Though no scholar, she was scrupulous, attentive, and curious. She slept little and worked hard. Was she a populist? Among those who define themselves as such, she stands as a symbolic figure because she was brought down in 1990 by the Tories’ europhile wing. Certainly, the British political establishment always looked down on this shopkeeper’s daughter. And yet Thatcher’s defining quality, and the reason why we still speak of Thatcherism, is that she told people things that they didn’t want to hear. She may have not liked the eurocrats in Brussels, or the Sir Humphrey Appleby-style bureaucrats at home, but she never told people that they could blame those bureaucrats, or anyone else, for their own faults or failures. In a world where political success goes hand in hand with providing suitable scapegoats for voters, this is unusual, to say the least. Thatcher’s like won’t come around again.

Alberto Mingardi is director general of the Italian free-market think tank, Istituto Bruno Leoni. He is also assistant professor of the history of political thought at IULM University in Milan, a presidential scholar in political theory at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow at the Cato Institute.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)