Hot Flash By Eric Cox

Curtain Time for Hitler

Downfall (Der Untergang)

Released by Newmarket Films

Rated R for strong violence, disturbing images, and some nudity

Previous Columns

04/06/05 - Schiavo, the Pope, and life lessons

04/04/05 - Al-Qaeda and poverty

04/01/05 - Crossing the threshold

03/30/05 - Boston Legal, meet Terri Schiavo

Click here to view the archives

This month marks the sixtieth anniversary of the effective end of perhaps the most astonishingly evil rgime in human history.

When Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945, Germany had already been defeated in World War II, though Hitler had resolutely refused to surrender.

In the new German film Downfall (Der Untergang), which depicts the Nazi regime's final days deep in a bunker beneath Berlin, Hitler (Bruno Ganz) positively bristles at the merest suggestion of retreat. When his generals ask him to consider the consequences for Berlin's civilian population of prolonging the war, an erratic Hitler retorts that the German people are cowards for losing the war and will pay with their blood.

The same attitude is resolutely held by Hitler's propagandist Joseph Goebbels (Ulrich Matthes), who later in the film coolly states that when the Germans gave the Nazi Party an electoral mandate, they took the risk that Hitler would fail and effectively handed him a knife to be put to their throats.

No one needs to be reminded of the vicious cruelty of the Nazis, of course, but the positively chilling effect of Downfall is that it presents such scenes in documentary fashion, presenting comments like these in the context of other scenes in which characters like Hitler and Goebbels behave like normal, well-adjusted human beings. These are not caricatures. There are no ominous musical cues to tell us when we are to feel anger, surprise, sadness, or fear. Downfall is like no other World War II movie I have ever seen, and it is by far one of the best.

Some critics, notably David Denby of the New Yorker, have excoriated Downfall for presenting a sympathetic portrait of Hitler. Nothing could be further from the truth. There is nothing sympathetic about this Hitler. As portrayed by the brilliant Bruno Ganz, the Hitler of Downfall is a charismatic, intelligent, paranoid, delusional, ambitious, reflective, despicable, living, breathing human being. It is an eery, disturbing performance.

What is so remarkable is that Ganz manages to be convincing whether he is portraying the unbelievably heartless Hitler, or the Hitler who at times is gentle and kind toward his aptly named young secretary, Traudl Junge (Alexandra Maria Lara).

Screenwriter Bernd Eichinger and director Oliver Hirschbiegel clearly intend for the naive Junge to be the conduit through which we experience and grapple with the movie. The film is based on Junge's memoir, and the opening scene depicts Junge arriving at the bunker with a group of other secretaries in the middle of the night for an interview with the Fuehrer.

Whether or not Junge's naivete is credible remains a source of great controversy in Germany today, as a younger generation asks how their parents and grandparents could have been as ignorant of the Nazis' atrocities as some, like Junge, claim to have been.

As for the screen version of Downfall, no excuses are offered for the Traudl Junges of the world. The film does not present Junge as blissfully unaware of Hitler's attitude toward Jews, the so-called survival-of-the-fittest, or the duty of all Germans to die for their Fuehrer: Junge hears all of this. Rather, the film presents her as constantly amazed, bewildered, and horrified by Hitler's statements, very much like a child who finds it impossible to reconcile her grandfather’s tenderness with his casual racism.

Junge's reaction is plausibly presented in Downfall, though it certainly will not be the reaction of any contemporary viewer. It is foolish for astute critics like Denby to believe that Western audiences would react to a film like Downfall with anything like moral confusion. Realizing that even someone as brutal as Hitler loved his dog is not the type of thing that could lead a reasonable person to excuse the Holocaust. On the contrary, forcing oneself to draw distinctions between an individual's capacity for warm feelings on one hand and the moral content of his actions on the other is a precondition for sound moral judgment. Would that more Traudl Junges had been capable of drawing such distinctions.

But enough about the silly controversy surrounding Downfall. It is a remarkable, hair-raising, thoroughly researched, two-and-a-half-hour movie well worth viewing. Unfortunately, you won’t get the chance to see many movies like it.

Eric Cox is a research fellow at the Sagamore Institute for Policy Research (SIPR) and a movie columnist for http://www.TAEmag.com.

"Government is not reason; it is not eloquent; it is force. Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master." - George Washington

Saturday, April 09, 2005

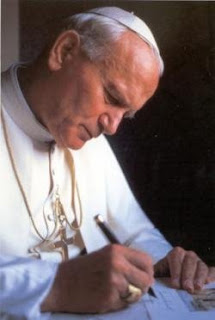

Joseph Bottum: John Paul the Great

From the April 18, 2005 issue of The Weekly Standard

Statesman and prophet, he overcame the poverty of the possible.

by Joseph Bottum

04/18/2005, Volume 010, Issue 29

History labors--a worn machine, sick with torsion, ill-meshed--and every repair of an old fault ruptures something new. Or so it seems, much of the time. Our historical choices are limited, constrained by the poverty of what appears possible at any given moment. To be a good leader is, for most figures who walk the world's stage, merely to pick the best among the available options--to push back where one can, to hold on to the good that remains, to resist a little the stream of history as it seems to flow toward its cataract.

For the past decade and a half, John Paul II was a good leader. He had his failures: losing the fight for recognition of Christianity in the European constitution, watching the democratic energy he generated during his 1998 visit to Cuba dissipate without much apparent damage to Castro's dictatorship, seeing his efforts to influence China's anti-religious regime peter out. But he had his successes as well: convincing even his bitterest opponents in the Church to join in at least the verbal rejection of abortion, regularizing Vatican relations with Israel to allow his millennial visit to the Holy Land, inspiring the defeat of the Mafia in Sicily.

With the drama of his final illness and death, he offered a lesson about the fullness, the arc, of human life. With the prophetic voice he used in his later writings, he pointed to spiritual possibilities that were being closed by what he once called the "disease of superficiality." Always he was present, one of the world's conspicuous figures, pushing on history where he could, guiding the Church as much as it would be guided, choosing the best among the available options--doing all that a good leader should.

But before that--for over a decade at the beginning of his pontificate, from his installation as pope in 1978 through the final collapse of Soviet communism in 1991--John Paul II was something more, something different, something beyond mere possibility. He wasn't simply a good leader. He was inspired, and he seemed to walk through walls.

Certain images remain indelibly fixed--the skeptical Roman crowd, for instance, falling in love with the new Polish pope in the first seconds of his pontificate as he gave his lopsided smile and called out, not in Latin, but Italian, from the papal balcony: "I don't know if I can make myself clear in your . . . our Italian language. If I make a mistake, you will correct me." He had a perfect sense of timing, as the actor John Gielgud observed after watching him, and in the whirlwind of those early years he seemed incapable of doing anything that wasn't news: skiing, mountain-climbing, gathering crowds of millions to pray with him everywhere from Poland to Australia, performing the marriage of a Roman street-sweeper's daughter because she'd had the pluck to ask him--snapping the Lilliputian threads of courtly precedent and royal decorum with which the Vatican curia traditionally tied down popes as though he didn't even notice.

The "postmodern pope," American magazines dubbed him, caught up in the media circus of his superstar status, the John Paul II magical mystery tour that swept across the globe through the 1980s. Certainly he had, all his life, the elements of stardom--the whole package of good looks, and charm, and curiosity, and intelligence, and physical presence, and, especially, an obvious and easily triggered sort of joy: the ability to please and the ability to be pleased that combine to make a man seem radiantly alive.

As a young priest, he was a polished, careful subordinate, clearly destined for high office in the Church--but he was also a recognized minor poet during a period when Polish poetry was the most flourishing in the world. As archbishop of Krakow, he was a full-time political player in the complex dance of Soviet-dominated Poland--but he was also an important philosophical interpreter of Thomistic metaphysics and Husserlian phenomenology, teaching courses at the Catholic University of Lublin, the only non-state university in the Communist world. As pope, he was a mystic who spent hours a day in solitary prayer--but he was also a natural for television. He seemed perfectly at home receiving the stately bows of ambassadors in the Clementine throne room--but when thousands of teenagers in Madison Square Garden chanted at him, "John Paul II, we love you," he was equally comfortable winning their hearts by shouting back: "Woo-hoo-woo, John Paul II, he loves you!"

And yet, to call all this "postmodern"--to imagine these elements are simple contradictions, absurdly juxtaposed in a characteristically postmodern way--is to believe something about John Paul II that he himself never did. It is to imagine that helicopters are ridiculous beside devotion to the Blessed Virgin, or that prayer gainsays philosophy, or that faith ought not to go with modern times.

This is another form of the poverty of the possible, the thinness of the choices and narratives that seem available at any particular time. Every step John Paul II took in those early years was a denial that our options were as limited as they appeared--in the political life of the world, in the religious life of the Church, and in the intellectual life of our cultures. For the impoverished imagination of the time, he seemed both far behind and far ahead of the rest of the world. But he never saw his medievalism as a reactionary antimodernism, or his modernism as an enlightened anti-medievalism. Christianity always seemed to him simultaneously an ancient faith and the newest hope for the world. He prayed constantly that he would live long enough to see the Jubilee of 2000, for he thought he was called to shepherd humankind into the third millennium that he claimed would be a "springtime of evangelization."

Toward the end of his pontificate, the tyranny of available options may have begun to close in on him. Certainly, in the first days after his death on April 2, the media have proved incapable of picturing him in any way other than caught in the clash of accepted political categories. John Paul II was a voice for peace--but he hated abortion! He was a radical critic of materialism--but he rejected women's ordination! He was one of the architects of the great opening of the Church at the Second Vatican Council--but he disciplined heterodox Catholic theologians!

The New York Times oddly and disturbingly used the pope's death as an occasion to editorialize in favor of euthanasia: "Terri Schiavo was a stark contrast to the passing of this pontiff, whose own mind was keenly aware of the gradual failure of his body. The pope would certainly never have wanted his own end to be a lesson in the transcendent importance of allowing humans to choose their own manner of death. But to some of us, that was the exact message of his dignified departure." It's hard to imagine a more egregious use of the word "transcendent" or a more grotesque inversion of the legacy of a man who always insisted that life wasn't a choice but a gift.

In truth, however, the Times was merely one among many publications that saw the pope only through the lens of current social politics. In all the thousands of obituaries that have appeared in the past week, hardly one failed to speak of the pope's "contradictions" somewhere along the way.

There's a reason. John Paul II's work in the Church must seem a hodgepodge when explained with the old narrative of Vatican II as entirely a struggle between liberal reformers and conservative traditionalists. His theology of the body, laid out in four years of addresses he began in 1979, must appear a mess when encountered with the view that libertines and reactionaries divide between them the only possible ways to think about human sexuality. And his politics of rightly ordered freedom must be unintelligible in a world that thinks itself limited to the alternatives of tyranny and radical license.

For the man himself, there was no contradiction at all, and he spent his pontificate trying to create new possibilities for history. You can see it perhaps most clearly in the defeat of communism--when he showed his ability to open doors where the rest of the world saw only walls.

After an unscheduled discussion during the 1979 papal tour of the United States, national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski joked that when he met with President Carter, he had the impression of speaking to a religious leader, and when he met with John Paul II, he felt he was talking to a world statesman. It was a joke with a bite. Of all American presidents, Jimmy Carter may have been the one most constrained by his thin conception of the available options, and all he could do was complain--in that failing voice of the would-be prophet he always seemed to end up using--that things ought to be different than they seemed to be.

John Paul II made them different. There's a temptation to overestimate the pope's role in the demise of Soviet communism. The labor unions, the anti-Stalinist intellectuals, and the churches all contributed enormously. The United States' long resistance during the Cold War, through presidents from Truman to Reagan, held Soviet expansion at bay while the Marxist economies ground toward their collapse: "We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us" ran a factory workers' joke at the time in the Russian satellites behind the Iron Curtain.

And yet, however weak the Communist edifice may have been in actuality, it still seemed formidable, and the pope was at the center of the cyclone that blew it down. The KGB's Yuri Andropov foresaw what John Paul II would be, warning the Politburo in Moscow of impending disaster in the first months after the Polish cardinal became pope. Figures from Mikhail Gorbachev to Henry Kissinger have looked back on their careers and judged that the nonviolent dissolution of the Communist dictatorships would not have happened without John Paul II.

"How many divisions has the pope?" Stalin famously sneered. As it happens, with John Paul II, we have an answer. At the end of 1980, worried by the Polish government's inability to control the independent labor union Solidarity, the Russians prepared an invasion "to save socialist Poland." Fifteen divisions--twelve Soviet, two Czech, and one East German--were to cross the border in an initial attack, with nine more Soviet divisions following the next day. On December 7, Brzezinski called from the White House to tell John Paul II what American satellite photos showed about troop movements along the Polish border, and on December 16 the pope wrote Leonid Brezhnev a stern letter, invoking against the Soviets the guarantees of sovereignty that the Soviets themselves had inserted in the Helsinki Final Act (as a way, they thought, of ensuring the Communists' permanent domination of Eastern Europe). Already caught in the Afghanistan debacle and fearing an even greater loss of international prestige and good will, Brezhnev ordered the troops home. Twenty-four divisions, and John Paul II faced them down.

When President Carter urged Americans in 1977 to overcome their "inordinate fear of communism," he clearly thought the only path out of the Cold War was agreement to the continuing existence of Communist regimes. This was the lie John Paul II was never willing to tell. It remains a mystery what the organizers of the annual "World Day of Peace" were hoping for when they asked the pope to contribute a reflection in 1982, but what they got from the apostle of peace was a letter denouncing the "false peace" of totalitarianism. In the end, the path out of the Cold War was neither Henry Kissinger's hard realpolitik nor Jimmy Carter's soft détente. It was instead John Paul II's insistence that communism could not survive among a people who had heard--and learned to speak--the truth about human beings' freedom, dignity, and absolute moral worth.

Think of the number of regimes based on lies that gave way without violent revolution during his pontificate. The flowering of democracy was unprecedented, and he seemed always to be present as it bloomed. There was Brazil, where the ruling colonels allowed the free elections that replaced them. There was the Philippines, where Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos fled from marchers in the street. There were Nicaragua, and Chile, and Paraguay, and Mexico. And looming over them all was the impending disintegration of the Soviet empire in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, Latvia--on and on, people after people who learned from the pope a new possibility for history, born from an ability to hear and speak the truth about the regimes under which they lived.

For John Paul II, the possibility of political truth was a philosophically obvious fact, demanded by the theory of personalism he developed as he used the modern phenomenology of Edmund Husserl to move intellectually beyond the dry versions of neo-Thomistic philosophy he had studied in seminary. It was a theological fact, as well, derived from--and pointing back toward--the awareness that human beings are created in the image of their free Creator. It was even a historical fact, learned during the long humiliation of Poland first by Nazi Germany and then by Soviet Russia while he was young. And it became, in the end, a mystical fact for John Paul II, joined--through Mary and the secrets of Fatima--to God's direct providence in history.

The mystical unity begins, for the pope, in what the papal biographer George Weigel calls the "shadowlands." Yuri Andropov's grim predictions about the impact of the Polish pope did not fall on deaf ears. On November 13, 1979, the Central Committee in Moscow approved a KGB plan entitled "Decision to Work Against the Policies of the Vatican in Relation with Socialist States." Much of the document dealt with issuing anti-Catholic "propaganda" in the Soviet bloc and the use of "special channels" in the West to spread disinformation about the pope. But another section ordered the KGB to "improve the quality of the struggle" against the Vatican.

What this meant became completely clear only with evidence released just last month. Elements of the Soviet security forces, working through the Bulgarian secret service, made contact with a Turkish assassin named Mehmet Ali Agca and aimed him at the pope. And on May 13, 1981, Agca shot John Paul II in St. Peter's Square with a Browning 9-mm semiautomatic pistol, striking him in the belly to perforate his colon and small intestine multiple times. In the pope's last book, Memory and Identity--a collection of philosophical conversations that appeared in Italy this February--he shows that he always knew the origin of Agca's attempt on his life: "Someone else masterminded it and someone else commissioned it." The assassination attempt was a "last convulsion" of communism, trying to reverse the historical tide that had turned against it.

But it was also something more. "One hand fired, and another guided the bullet," he tried to explain after he left the hospital. On May 13, 1991, Pope John Paul II traveled to Portugal and placed the bullet with which he had been shot ten years before in the crown of the statue of Mary at the site of her original apparitions at Fatima. It wasn't till 2000 that the Vatican offered an explanation--and, along the way, revealed what had been called "the third secret of Fatima," a prophesy about a pope gunned down, hidden since it was given by the Blessed Virgin to three Portuguese children on July 13, 1917.

For John Paul II, the pieces all came together: the endless rosaries prayed since 1917 for the "conversion of Godless Russia" as the Blessed Virgin had asked, the "secret" vision of a shot pope she had further revealed at Fatima, the thirteens repeated in the dates, the special devotion to Mary that he marked with the large "M" on his coat of arms--and the truth of human freedom, asserted against the Communist lie.

He had sophisticated philosophical, theological, and historical reasons to see chances for political change where even the good leaders of his time saw only the poverty of the possible. He had poetic and aesthetic reasons, as well, to suppose it all somehow made sense: If "the word did not convert, blood will convert," he said of martyrdom in "Stanislaw," the last poem he wrote before becoming pope. But we cannot understand the man--we cannot grasp how, for him, history was always open to new possibilities--unless we also understand that it was, most of all, a mystical truth: the unity of things seen and unseen, the coherence of the spirit and the flesh.

"The intellect of man is forced to choose perfection of the life, or of the work," William Butler Yeats once sadly observed. But this was yet another thinness of possibility--that we can make either our lives or our works beautiful and whole, but not both--which John Paul II refused to admit.

In his magisterial biography Witness to Hope (first published in 1999, and soon to appear in a third and updated edition that carries the story through the pope's death), George Weigel reports innumerable telling facts about the life of Karol Wojtyla before he became John Paul II at age 58, the youngest pope in more than a hundred years. His mother died when he was 8, for instance--and then his only brother when he was 12, and his father eight years later: "At the age of 20," he would look back to say, "I had already lost all the people I loved."

But though Weigel reports such facts and the pope's own occasional reflections upon them, he hardly ever draws a psychological conclusion--and he never offers a picture of what Wojtyla's subjective life was like or makes a guess about the interior monologue of his emotional life. On a first reading, this resolute refusal to psychologize may seem odd: People are their psyches, after all. We read biographies to understand their subjects, which we do only as we learn who they are and the psychological causes that shaped them into those particular people.

Indeed, John Paul II himself told Weigel in a 1996 interview, "They try to understand me from outside. But I can only be understood from inside." To the general reader of biographies, there is something absurd when Weigel quotes this line--and immediately goes on to describe the "inside" of Karol Wojtyla by mentioning the history of the Nazi and Soviet occupations of Poland, the philosophical necessity for grounding humanism and freedom in the truth about human existence, and the theological centrality of the virtue of hope.

And yet, over the last few years--as the world watched John Paul II teach, even with his death, one last lesson about the shape of human life--it has become clear that Weigel was right to think of the pope in this way. We have millions of words from the man: the 14 major encyclicals, 15 apostolic exhortations, 11 apostolic constitutions, and 45 apostolic letters; the popular books like Crossing the Threshold of Hope, scribbled on yellow pads during long plane flights; the scholarly works he wrote as a young theologian; the thousands of prayers and exhortations he delivered during the innumerable audiences he tirelessly gave as pope. And in all those words, there is hardly a hint of what a psychologist would demand: a persona that somehow stands apart from the history through which he lived and the intellectual growth he experienced.

It is not that he was a private person, in the usual way we speak of such people: refusing to discuss themselves and burying their psyches in their public work. It is, rather, that the center of the man--the focal point of his unified life--was the narrative arc of his story: what he was and how he got that way.

The closest John Paul II came to explaining himself may have been Roman Triptych: Meditations, a collection of three poems written during the 2003 papal trip to Poland, which he foresaw would be his last visit home. The only new poetry the pope published during his pontificate, the book is not first-class verse. But it remains fascinating autobiography, for each poem of the triptych shows a man considering human existence in one of its apparently divided aspects: as the life of the artist, as the life of the intellectual, and as the life of the believer. And through all three of the linked poems, the author seeks to express the unity he could always sense was drawing it all together.

It was a unity that derives, finally, from God's providential purpose in history. But history and Karol Wojtyla's biography grew together, more and more as the years went by, and the divine presence he felt in history joined the divine presence he could feel in the arc of his life. The man was his story--and in that story, he could seek perfection of both the life and the work.

Consider just one scene from his early life. When the Nazis began their occupation of Poland in 1939, they were determined to do more than conquer the country. "A major goal of our plan is to finish off as speedily as possible all troublemaking politicians, priests, and leaders who fall into our hands," the German governor, Hans Frank, wrote to his subordinates from the office he established in Krakow's old royal residence, Wawel Castle. "I openly admit that some thousands of so-called important Poles will have to pay with their lives, but . . . every vestige of Polish culture is to be eliminated."

The Nazis' destruction of Poland's Jews was more deliberate and systematic than their slaughter of Poland's Catholics, but the unified goal was clear from the beginning: By the time he was done overseeing the murder of thousands of priests and hundreds of college professors, and the deaths of millions of ordinary citizens along the way, Frank boasted, "There will never again be a Poland."

Among the schemes for the elimination of Polish culture was the closing of all secondary schools and universities--including seminaries. When the 22-year-old Karol Wojtyla entered studies for the priesthood in 1942, the entire Catholic educational system was underground and illegal. The first years of his priestly formation were snatched in secret, usually at night and always while waiting for death to find him as it found so many others in Poland.

When Frank closed the seminary in Krakow, up the hill near Wawel Castle, the German S.S. took over the building and used it for the next five years as an administrative headquarters. And when the Nazis abandoned Krakow on January 17, 1945, as the Red Army's 1st Ukrainian Front closed in on the city, the archbishop--Adam Stefan Sapieha, the "uncrowned king of Poland" who had dared to mock Frank openly--quickly moved to reclaim the seminary before the Russians seized it.

It turned out that, by the end of the war, the S.S. had begun using the building as a makeshift jail, and Sapieha found the seminary with its roof collapsed, its windows shattered, and its rooms scarred from the open fires the inmates had built to keep from freezing. Worst of all was the failed plumbing, and in the hurry to save the building, young Wojtyla and another seminarian were sent in with trowels to clear out the cold, hard feces left by the prisoners.

Picture, for a moment, that scene: the brilliant 24-year-old--already known among his contemporaries as an actor and a playwright, already clearly destined for great things, already arrived at the fullness of his intellectual powers--chipping away for days in rooms full of frozen excrement.

And contrast it with another scene, 34 years later, when Karol Wojtyla made his first trip to Communist Poland as Pope John Paul II. He arrived on June 2, 1979, and by the time he left eight days later, 13 million Poles--more than one-third of the country's population--had seen him in person as he traveled from Warsaw, to Gniezno, to the shrine at Czestochowa, and ended in Krakow. Nearly everyone else in the nation saw him on television or heard him on the radio. The government was frightened to a hair trigger, and outside observers all had the sense that the Communist regime was doomed, one way or another, from the first moment the pope knelt down and kissed his native soil.

The enormous crowds could sense it, too. On the night of Friday, June 8, tens of thousands of young people gathered outside St. Michael's Church in Krakow for a promised "youth meeting" with the pope. "Sto lat! Sto lat!" they shouted over and over: "Live for a hundred years!" Abandoning his prepared speech, John Paul II joked with them--"How can the pope live to be a hundred when you shout him down?"--in an effort to calm the situation. But by 10:30 the emotions of the young crowd had reached a fever pitch.

The temptation for demagoguery must have been enormous: tens of thousands of young Poles--children, really--waving crosses above their heads, chanting in their ecstatic madness for this man to lead them, hungry for martyrdom, ready to trample down the government troops that waited nervously to meet them. A single hint, a single gesture, and the city could have been his--the whole of Poland, perhaps, for the emotion was electric across the country. But all that blood would have been his, too, and he knew the time was not yet right. "It's late, my friends. Let's go home quietly," was all he said, and inside the car that carried him away, John Paul II wept and wept, covering his face with his hands.

For anyone else, these two scenes would stand in contradiction: Once this man was so powerless that he was forced in the middle of a frozen January to clean open rooms that had been used as toilets, but later he was so powerful that thousands of people would have gladly died if he had but lifted his hand. For Karol Wojtyla, however, there seemed no contradiction at all. They were both demanded by the vocation to which God had called him. They were both involved with service and obedience. They were both the next thing that needed to be done.

This is the only way to make sense of John Paul II. He spent his life refusing the poverty of the possible, the worldly notion that our choices and explanations are limited to contemporary political categories--and all the apparent contradictions in his thought melt away when we realize he was perceiving options that no one else could see.

With his 1991 encyclical on democratic freedom and economics, Centesimus Annus, he issued what is by any objective measure the most pro-Western--pro-American, for that matter--document ever to come from Rome. And then, with the denunciations of the "culture of death" in the 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae, he issued Rome's most anti-Western and anti-American document. It looks like an impossible combination, until we remember that between them came the 1993 encyclical Veritatis Splendor--"The Splendor of Truth," joined with Centesimus Annus and Evangelium Vitae as the three-part message that formed the central theological achievement of his pontificate. The unity of truth--the only sustainable ground for a healthy society--is what lets us grasp both the rightness of democracy and the murderousness of abortion.

That's not to say his pontificate was an unbroken string of successes. He felt the Christian schism deeply, but his many overtures to the Eastern Orthodox Churches were mostly unrequited, and the healing of Christianity is still far away. He never understood the Middle East with the same clarity that he grasped Eastern Europe, and after the fall of Soviet communism he didn't have the same direct impact on world history. When he opposed the first Gulf War in 1991--and allowed Iraq's murderous deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz, to pay a state visit to Rome and Assisi before the second Gulf War in 2003--he seemed to have become locked into a single model for democratic reform, as though Saddam Hussein could be overcome with the same nonviolent, soft-power techniques that had worked in Catholic countries from Poland to the Philippines.

Similarly, he often appeared to have greater success evangelizing the rest of the world than he did evangelizing his own Church. The orthodoxy of the new Catechism he issued in the 1990s and the example of his personal spirituality stopped the slide of post-Vatican II Catholicism into a theological simulacrum of liberal Protestantism. His unique connection to young people--manifested at the huge outpourings for World Youth Day events--created a new generation of "John Paul II Catholics" among young people who have never known another pope. But on the older generations formed before his pontificate, particularly in America and Western Europe, he found little purchase. The liberal Catholic establishment never forgave him for either his failures or his successes, and they blamed him when the American priest scandals became public in 2002--though the priests involved were of the generation formed before John Paul II became pope.

But along the way, he refused to falter. He seems never to have been frightened of anything in his life, and he expected everyone else to share his confident courage: "Be not afraid," he began his pontificate by echoing from the gospel. The 1981 bullet wound slowed him down a little, a 1994 fall in his bath slowed him more, and by the time he reached his 82nd birthday in 2002, he was showing the signs of his impending death. But even at the end he was "a body pulled by a soul" to remain active, as the Vatican official Joaquin Navarro-Valls put it, and his constant motion throughout his life seems breathtaking.

In the 27 years of his pontificate he was seen in the flesh more often than anyone else in history--by over 150 million people, according to one estimate. He traveled to more than 130 countries, created 232 cardinals, and never slowed in the Vatican's endless schedule of audiences, consistories, synods, and meetings. He named 482 saints and beatified another 1,338 people, more than all his predecessors, in his confident belief that the possibility of sanctity was still alive in the world. He produced the first universal Catechism since Vatican II, revised canon law, reorganized the Curia, and made huge advances in Jewish-Christian and Catholic-Protestant relations.

That set of features--his complete courage and his boundless energy--gave him enormous freedom, particularly when combined with his certain conviction that there must exist a way to living in truth no matter how thin the merely possible seemed. He was, in fact, the freest man in the twentieth century. As a measure of his greatness, think of him this way: He could have been a Napoleon. He could have been a Lenin. Instead, he was the vicar of Christ, the heir of St. Peter, steward of a gospel recorded long ago.

History labors down its worn tracks, and the poverty of human possibilities leaves us few choices. Or so it often seems.

But not always. Not while we remember that living in truth is always possible. Not while we remind ourselves of the message of hope preached ceaselessly by Karol Wojtyla. Not while we recall John Paul the Great.

Joseph Bottum is a contributing editor to The Weekly Standard and editor of First Things.

© Copyright 2005, News Corporation, Weekly Standard, All Rights Reserved.

Paul Johnson: The Philosopher-Pope

JOHN PAUL II

The Philosopher-Pope

His love for life made him an unflinching upholder of Catholic teaching.

BY PAUL JOHNSON

The Wall Street Journal

Saturday, April 9, 2005 12:01 a.m. EDT

LONDON--The death of John Paul II removes from the world a great force for order and rectitude. He was often presented as a conservative, especially by liberal critics within the church. But this was a misreading of his character and indeed of his record. This great pontiff was essentially a defender, promoter, protector and enhancer of life: life in all its forms, as God created them, but especially human life.

He sought to limit, almost to vanishing point, the occasions on which the state, let alone individuals, might legitimately extinguish or frustrate life. He had spent his manhood largely under the tyranny of the two vilest anti-life systems the world had ever seen: Nazism and Communism, together responsible for the unnatural deaths of over 120 million people in Europe and Asia. He had seen at close quarters the appalling consequences which inexorably follow when authority is directed by philosophy contemptuous of life.

John Paul was a philosopher by inclinations and training, and his philosophy was infused by reverence and respect for human life in all its multitudinous epiphanies. Humans, albeit fallible and often foolish, were made in God's image, and to take a life, without the strongest possible justification, was an assault on God.

The pope's love of humanity was expressed in many ways: by his constant travels to every corner of the world, so that he saw more of his billion-strong global flock than all his 263 predecessors put together, and was himself seen in the flesh by more people than anyone else in history. A formidable linguist, he took the trouble to learn a few phrases in nearly 100 different tongues so that he could communicate directly with the people who came to see him in St. Peter's Square from all over the world.

This love for life made John Paul a stern and unflinching upholder of traditional Catholic teaching in three important respects. He refused to countenance any form of artificial contraception, allowing Catholics to plan their families only by natural methods. As a priest he had made a special study of the medical sciences which affect families, and as Archbishop of Krakow he set up an institute devoted to the problems of conception, birth and parenting. He believed to his dying day that nature was the only reliable and health-preserving guide in such matters.

The pope was likewise a vehement opponent of any form of euthanasia, believing that life in the extremely old or chronically sick, even seemingly insensible sufferers, was just as precious--and to be defended just as passionately--as in the young and vigorous. To him, the battle to preserve life was all-important, uncompromising and perpetual.

In his last years, and especially his last weeks, he fought this battle himself with all the obstinacy of his enormous will. His struggle to perform his global duties right to the end was a painful but hugely effective demonstration against the iniquity of a compulsory retirement age, but also a gesture of protest against all those who would sideline, condescend to, and render impotent the very old. He reminded the world that the aged and frail might lack everything else but could be rich in the quality always in the shortest possible supply in the world--wisdom. His last gift to humanity was a moving and electrifying demonstration of what Christians call a bona mors--how to die.

John Paul was, perhaps, most vehement in his condemnation of abortion, especially when practiced under the sanction of law and on a huge scientific scale, in the clinics specially created to smother the spark of life before birth, which he compared to the death camps erected by Nazi and Soviet mass murderers. It was a sharp sword in his heart which filled him with righteous indignation that, after the world had been scourged for more than 50 years by the mass killings of totalitarianism, anti-life politicians, above all in the democracies, should have set up a holocaust of the unborn which has already--as he often asserted with awe and anger--ended the existence of more tiny human creatures than all the efforts of Hitler, Stalin and Mao combined.

But it should not be thought that John Paul's defense of life was conducted on principles seen as conservative. He was an absolute and implacable opponent of capital punishment, an issue on which he parted sorrowfully from many of his warmest admirers. He was most reluctant to admit the admissibility of war in almost any circumstances. He was wary of giving any kind of approval to President Bush's active war on terror, and plainly opposed the invasion of Iraq. It was his view that a righteous ruler, however tempted by the urge to end wicked regimes, should not set in motion events which would soon move out of control and perhaps cause evils far worse than those it was designed to end.

Not that the pope condoned terrorism in any form. He was never among those clergy in the West who mitigated their disapproval by pointing to legitimate grievances.

Indeed it would be hard to imagine a greater contrast between Pope John Paul, who spent his entire existence searching perpetually to prolong and preserve life, and that evil caricature of a spiritual leader Osama bin Laden, who from the moment he awakes, throughout the day, until he falls into a troubled sleep, directs his agents to end as many lives as possible, including their own (but never his). In their cataclysmic duality, these two men came as close as ever human beings do to embodying the principles of Good and Evil.

The pope was not content to speak out against political wickedness, and analyze it in his powerful encyclicals. Along with President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, he played an active and leading role in the overthrow of Soviet Communism and its despicable empire. The three great leaders did it together, and it could well be argued that the pope was the most effective of them.

This was a struggle for freedom, but also for justice. The pope always put the two together in his mind. Shortly before he died, he authorized publication of a little book of his reflections. The key chapter in it is an essay in which he argues that humanity is right to seed freedom but only if that freedom is used to do justice. And the essence of justice is to confer, preserve, protect, prolong and give meaning and value to life.

John Paul's philosophy was thus all of a piece: it was internally consistent in all its parts, a little masterpiece of human thoughtfulness and sense.

We did not know this when he was elected. I covered the Conclave, as I have covered all those held since World War II. In each case, the outcome, in terms of the pontificate which followed, has been quite different from all the predictions made at the time. I have no doubt that the same thing will happen this time, too.

Catholics believe that the Holy Spirit is all-powerful but moves in ways often mysterious, especially in the election of a pope. More than a quarter-century ago, we were given a man of powerful intellect, courage and determination, who possessed wisdom and charity in ample measure, and whose patient and vigorous work for his Church, and for humanity as a whole, was crowned with unusual success. We must pray that his successor is worthy of so rich a heritage.

Mr. Johnson, a historian, is the author of, among others, "A History of Christianity" (Touchstone, 1979). His most recent book is "Art: A New History" (HarperCollins, 2003).

Houston Chronicle: Clemens Ties Carlton With 329th Win

April 9, 2005, 1:27AM

Clemens does double duty

Rocket ties Carlton with 329th career win, drives in go-ahead runs with 6th-inning single

By JOSE DE JESUS ORTIZ

Copyright 2005 Houston Chronicle

• Boxscore • Clemens' debut: Photo gallery

• ASTROS/MLB: Full Chronicle coverage, boxscores, stats

As the Cincinnati Reds prepared to intentionally walk No. 8 hitter Willy Taveras in the sixth inning, Roger Clemens turned to Astros manager Phil Garner for instructions.

A pinch hitter would have been called for most pitchers, especially because the score was tied and a runner already was on base.

But Clemens is different. He's a once-a-generation righthander some consider the best pitcher in major-league history. With the game on the line, he has generally found a way to win.

So Garner let Clemens hit, and Clemens came through with a two-run single to beat the Reds 3-2 Friday night at Minute Maid Park.

Clemens, 42, excelled on the mound and at the plate to begin his 22nd season with his 329th victory.

"He's amazing," Garner said after the Astros handed the Reds their first loss of the season. "You're watching a legend. That's all there is to it. It's just absolutely amazing."

With the victory, Clemens moved into a tie with former Cardinals and Phillies star Steve Carlton for ninth on the all-time wins list.

"Here we are again talking about things I didn't think we'd be talking about," Clemens said after holding the Reds to one run on five hits with nine strikeouts in seven innings before a crowd of 36,382 at Minute Maid Park. "To tie Steve Carlton, he's one of the best ever, and to have my name alongside of him is a tremendous honor."

With the score tied at 1, Clemens stood on the verge of failure in the sixth. Showing the guile that has made him one of the best pitchers and competitors of all-time, he averted disaster in the top of the inning, then took care of the win with his bat.

"This guy honestly is just amazing," closer Brad Lidge said after collecting a four-out save. "He's just amazing to watch."

Clemens was at his competitive best after giving up consecutive singles to start the sixth. Ryan Freel led off the inning with a pinch single to center. D'Angelo Jimenez followed with a single to right, putting runners at the corners for Ken Griffey Jr.

Striking out Junior

Griffey worked the count to 3-0, but Clemens wasn't ready to give in. He teased Griffey with a 3-0 fastball out of the strike zone, fooling the slugger just enough to keep him from checking his swing in time.

Griffey fouled the next pitch to fill the count. With Jimenez running, Griffey took a backdoor slider for a called third strike. As Astros catcher Brad Ausmus threw to second, Freel took off for home.

Shortstop Adam Everett sprinted in front of the bag to take the throw and fire it home in time to double up Freel.

"I just happened to see (Freel) break early," Everett said. "Brad made a great throw to me. It was chest-high and gave me a chance to throw him out at home. Right there you're thinking you got Griffey, and you got (Sean) Casey (coming up next).

"If Griffey strikes out there, they normally don't try a double-steal right there, especially with Casey coming up. But they did."

Clemens, whose lone mistake was the 2-0 fastball Joe Randa ripped into the concourse behind the left-center field wall to tie the score in the fifth, got out of the sixth inning by striking out Casey on a 1-2 splitter.

Luke Scott, who tripled and scored on Jason Lane's sacrifice fly to give the Astros a 1-0 lead in the second inning, led off the bottom of the sixth with a single up the middle. Lane followed with a single to left. After Ausmus hit into a double play, righthander Matt Belisle intentionally walked Taveras, who then stole second.

"I was on deck, and when I looked at their catcher and they were going to walk Willy I turned to skip and said, 'What have we got?' " Clemens said. "He goes, 'Drive 'em in.' "

Few would have blamed Garner for calling on a pinch hitter, considering Mike Lamb had come off the bench Wednesday to drive in the winning runs.

But on this night, Garner didn't even consider hitting for Clemens.

"You know he's going to do it," Garner said. "You know he's going to do something. You just feel it in your bones that it's going to happen.

"It's his game. I can't think of anybody better I'd rather have that game in his hands. It's Roger's game. I made the decision that he was going another inning at least, so I let him have the game."

Aurilia can't make playClemens quickly fell behind 0-2, but he took the next three pitches to fill the count before hitting his two-run single up the middle. Though Reds shortstop Rich Aurilia made a diving stab at the ball, he couldn't keep his grip while attempting to throw to first.

After the ball popped up from Aurilia's grasp, a tremendous roar through the park greeted the 3-1 lead.

"I was fortunate to get 3-2 and got a ball (to hit)," Clemens said. "It seemed like first base was running from me, especially after I took a quick glance under my eye and noticed that they knocked the ball down to keep it in the infield."

jesus.ortiz@chron.com

Cy Young ceremony

In a pregame ceremony tonight, the Astros will honor Roger Clemens for extending his record Cy Young collection last season to seven with his first in the National League.

Clemens will receive gifts commemorating his achievement, but it's fair to say he probably won't get a burnt orange Hummer like the one Andy Pettitte and the rest of the two pitchers' former Yankees teammates purchased for the future Hall of Famer in 2003.

"He's gotten plenty enough gifts," joked Pettitte, Clemens' best friend on the club. "I don't think he needs anymore gifts."

Clemens does double duty

Rocket ties Carlton with 329th career win, drives in go-ahead runs with 6th-inning single

By JOSE DE JESUS ORTIZ

Copyright 2005 Houston Chronicle

• Boxscore • Clemens' debut: Photo gallery

• ASTROS/MLB: Full Chronicle coverage, boxscores, stats

As the Cincinnati Reds prepared to intentionally walk No. 8 hitter Willy Taveras in the sixth inning, Roger Clemens turned to Astros manager Phil Garner for instructions.

A pinch hitter would have been called for most pitchers, especially because the score was tied and a runner already was on base.

But Clemens is different. He's a once-a-generation righthander some consider the best pitcher in major-league history. With the game on the line, he has generally found a way to win.

So Garner let Clemens hit, and Clemens came through with a two-run single to beat the Reds 3-2 Friday night at Minute Maid Park.

Clemens, 42, excelled on the mound and at the plate to begin his 22nd season with his 329th victory.

"He's amazing," Garner said after the Astros handed the Reds their first loss of the season. "You're watching a legend. That's all there is to it. It's just absolutely amazing."

With the victory, Clemens moved into a tie with former Cardinals and Phillies star Steve Carlton for ninth on the all-time wins list.

"Here we are again talking about things I didn't think we'd be talking about," Clemens said after holding the Reds to one run on five hits with nine strikeouts in seven innings before a crowd of 36,382 at Minute Maid Park. "To tie Steve Carlton, he's one of the best ever, and to have my name alongside of him is a tremendous honor."

With the score tied at 1, Clemens stood on the verge of failure in the sixth. Showing the guile that has made him one of the best pitchers and competitors of all-time, he averted disaster in the top of the inning, then took care of the win with his bat.

"This guy honestly is just amazing," closer Brad Lidge said after collecting a four-out save. "He's just amazing to watch."

Clemens was at his competitive best after giving up consecutive singles to start the sixth. Ryan Freel led off the inning with a pinch single to center. D'Angelo Jimenez followed with a single to right, putting runners at the corners for Ken Griffey Jr.

Striking out Junior

Griffey worked the count to 3-0, but Clemens wasn't ready to give in. He teased Griffey with a 3-0 fastball out of the strike zone, fooling the slugger just enough to keep him from checking his swing in time.

Griffey fouled the next pitch to fill the count. With Jimenez running, Griffey took a backdoor slider for a called third strike. As Astros catcher Brad Ausmus threw to second, Freel took off for home.

Shortstop Adam Everett sprinted in front of the bag to take the throw and fire it home in time to double up Freel.

"I just happened to see (Freel) break early," Everett said. "Brad made a great throw to me. It was chest-high and gave me a chance to throw him out at home. Right there you're thinking you got Griffey, and you got (Sean) Casey (coming up next).

"If Griffey strikes out there, they normally don't try a double-steal right there, especially with Casey coming up. But they did."

Clemens, whose lone mistake was the 2-0 fastball Joe Randa ripped into the concourse behind the left-center field wall to tie the score in the fifth, got out of the sixth inning by striking out Casey on a 1-2 splitter.

Luke Scott, who tripled and scored on Jason Lane's sacrifice fly to give the Astros a 1-0 lead in the second inning, led off the bottom of the sixth with a single up the middle. Lane followed with a single to left. After Ausmus hit into a double play, righthander Matt Belisle intentionally walked Taveras, who then stole second.

"I was on deck, and when I looked at their catcher and they were going to walk Willy I turned to skip and said, 'What have we got?' " Clemens said. "He goes, 'Drive 'em in.' "

Few would have blamed Garner for calling on a pinch hitter, considering Mike Lamb had come off the bench Wednesday to drive in the winning runs.

But on this night, Garner didn't even consider hitting for Clemens.

"You know he's going to do it," Garner said. "You know he's going to do something. You just feel it in your bones that it's going to happen.

"It's his game. I can't think of anybody better I'd rather have that game in his hands. It's Roger's game. I made the decision that he was going another inning at least, so I let him have the game."

Aurilia can't make playClemens quickly fell behind 0-2, but he took the next three pitches to fill the count before hitting his two-run single up the middle. Though Reds shortstop Rich Aurilia made a diving stab at the ball, he couldn't keep his grip while attempting to throw to first.

After the ball popped up from Aurilia's grasp, a tremendous roar through the park greeted the 3-1 lead.

"I was fortunate to get 3-2 and got a ball (to hit)," Clemens said. "It seemed like first base was running from me, especially after I took a quick glance under my eye and noticed that they knocked the ball down to keep it in the infield."

jesus.ortiz@chron.com

Cy Young ceremony

In a pregame ceremony tonight, the Astros will honor Roger Clemens for extending his record Cy Young collection last season to seven with his first in the National League.

Clemens will receive gifts commemorating his achievement, but it's fair to say he probably won't get a burnt orange Hummer like the one Andy Pettitte and the rest of the two pitchers' former Yankees teammates purchased for the future Hall of Famer in 2003.

"He's gotten plenty enough gifts," joked Pettitte, Clemens' best friend on the club. "I don't think he needs anymore gifts."

Friday, April 08, 2005

Rolling Stone: Bruce Kicks up "Dust"

Springsteen to launch acoustic tour behind stark new disc

http://www.rollingstone.com

By Brian Hiatt

6 April 2005

"I've been happily busy," says Bruce Springsteen, taking a break from rehearsals for his spring tour. "When you're not working a lot, there is always one reason: You don't have the songs. But I have music to sing."

Springsteen will launch a solo acoustic tour in Detroit on April 25th, the night before he releases the spare new studio album Devils and Dust. "It's the opposite of playing with the E Street Band," he says of his second-ever solo outing.

Recorded without the E Streeters, Devils combines whispery acoustic story songs with stripped-bare, folk-and-country-inflected rock tunes. In many ways, Springsteen says, the album is a sequel to 1995's hushed The Ghost of Tom Joad, which inspired his first solo tour. "I wrote a lot of this music after those shows, when I'd go back to my hotel room," he remembers. "I still had my voice, because I hadn't sung over a rock band all night. I'd go home and make up my stories."

Springsteen recorded the basic tracks with producer Brendan O'Brien on bass and Steve Jordan (who's worked with Keith Richards and Springsteen's wife, Patti Scialfa) on drums, with recent E Street Band addition Soozie Tyrell overdubbing fiddle parts. At various points, the album employs a string section, horns, organ and electric guitar. But it all feels stark and sepia-toned. "I wanted to keep it raw," Springsteen says. "I think that's what's slipped out of a lot of modern country music, that certain sort of chill-to-the-bone sound."

As with Joad, many of the songs are set in the Southwest, with Spanish phrases studding the lyrics. "The lives of the new migrant population were interesting stories for me," Springsteen says. "I was just interested in the way the West and the Southwest feel in my imagination."

Springsteen had most of these tunes nearly finished by 1997 but put them aside in favor of a 1999 reunion tour with the E Street Band, which led to 2002's The Rising. The inspiration for reviving the solo material, Springsteen says, was a new song, "Devils and Dust," that he wrote in 2003 at the start of the Iraq War. ("I've got my finger on the trigger/But I don't know who to trust," it begins.) "It is basically a song about a soldier's point of view in Iraq," Springsteen says. "But it kind of opens up to a lot of other interpretations."

Springsteen tried recording the title track as both an angry rock song and an acoustic ballad, but it took the help of producer O'Brien -- who also worked on The Rising -- to bridge the gap. "Brendan found something that put it in the middle, where it picks up a little instrumental beef as it goes," says Springsteen. O'Brien took a similar approach to the rest of the album, helping Springsteen ditch Joad's low-fi sound and minimal arrangements for a more fleshed-out approach.

Among the standout tracks is "Reno," a disquieting ballad about a man's visit to a prostitute -- with an explicit reference to anal sex that won the album an "adult imagery" warning on its back cover. ("It's just what felt right for the song," Springsteen says.) "Long Time Comin'" is an exuberant, rocking love song; "All I'm Thinkin' About" is a buoyant, falsetto-laden lark; and "All the Way Home" is a soul ballad that Springsteen wrote for a 1991 Southside Johnny album, revisited here as a country-rock shuffle.

As he prepared for the Devils tour, Springsteen considered taking a small band on the road. "Nils [Lofgren] and some other folks came in for rehearsals to give me a sense of if I wanted to go with something bigger," he says. "But what tends to be dramatic is either the full band or you onstage by yourself. Playing alone creates a sort of drama and intimacy for the audience: They know it's just them and just you."

The tour -- which hits venues as large as 5,000-seaters -- will focus on the new album, along with material from Joad and 1982's Nebraska, and stripped-down takes on songs from The Rising. "It's not about acoustic versions of my hits -- that's what's not going to happen," says Springsteen, who will also perform on an April 23rd episode of VH1's Storytellers. "I want to forewarn potential ticket buyers: I'm not going to be playing an acoustic version of 'Thunder Road.'"

Springsteen last broke out his hits on last fall's Vote for Change Tour, followed by solo sets at rallies for John Kerry. What did he take away from his stint in partisan politics? "I've tried not to think about it," Springsteen says. "But it was an experience that I'm glad I put myself into. There was a lot of idealism out there -- I took a lot of that with me."

Meanwhile, Springsteen has already written songs that he says could form the basis for another E Street Band album and tour. "I've got some [rock] things, but I haven't heard them back yet," he says. "You've always got to hear them back to know if they're good or not. I'm not sure if it's the very next thing. But I certainly imagine we'll be doing that sooner rather than later."

Bruce Springsteen's initial tour dates:

4/25: Detroit, Fox Theater

4/28: Dallas, Nokia Theater at Grand Prairie

4/30: Phoenix, Glendale Arena

5/2: Los Angeles, Pantages Theater

5/3: Los Angeles, Pantages Theater

5/5: Oakland, CA, Oakland Theater

5/7: Denver, Convention Theater

5/10: St Paul, MN, Xcel Energy Center

5/11: Chicago, Rosemont Theater

5/14: Fairfax, VA, Patriot Center

5/15: Cleveland, OH, CSU Convocation Center

5/17: Philadelphia, Tower Theater

5/19: East Rutherford, NJ, Continental Airlines Arena

5/20: Boston, Orpheum Theater

5/24: Dublin, Ireland, the Point

5/27: London, Royal Albert Hall

5/28: London, Royal Albert Hall

5/30: Brussels, Belgium, Forest National

6/1: Barcelona, Spain, Pavello Olimpic Badalona

6/2: Madrid, Spain, Palacio De Deportes de la Comunidad

6/4: Bologna, Italy, Palamalaguti Arena

6/6: Rome, Italy, Palalottomatica Arena

6/7: Milan, Italy, Milan Forum

6/11: Hamburg, Germany, Color Line Arena

6/12: Berlin, Germany, ICC6/13: Munich, Germany, Olympia Hall

6/15: Frankfurt, Germany, Festhalle

6/16: Dusseldorf, Germany, Phillipshalle

6/19: Rotterdam, Netherlands, Ahoy

6/20: Paris, Bercy

6/22: Copenhagen, Denmark, Forum

6/23: Gothenberg, Sweden, Scandinavium

6/25: Stockholm, Sweden, Hovet

More Bruce Springsteen

http://www.rollingstone.com

By Brian Hiatt

6 April 2005

"I've been happily busy," says Bruce Springsteen, taking a break from rehearsals for his spring tour. "When you're not working a lot, there is always one reason: You don't have the songs. But I have music to sing."

Springsteen will launch a solo acoustic tour in Detroit on April 25th, the night before he releases the spare new studio album Devils and Dust. "It's the opposite of playing with the E Street Band," he says of his second-ever solo outing.

Recorded without the E Streeters, Devils combines whispery acoustic story songs with stripped-bare, folk-and-country-inflected rock tunes. In many ways, Springsteen says, the album is a sequel to 1995's hushed The Ghost of Tom Joad, which inspired his first solo tour. "I wrote a lot of this music after those shows, when I'd go back to my hotel room," he remembers. "I still had my voice, because I hadn't sung over a rock band all night. I'd go home and make up my stories."

Springsteen recorded the basic tracks with producer Brendan O'Brien on bass and Steve Jordan (who's worked with Keith Richards and Springsteen's wife, Patti Scialfa) on drums, with recent E Street Band addition Soozie Tyrell overdubbing fiddle parts. At various points, the album employs a string section, horns, organ and electric guitar. But it all feels stark and sepia-toned. "I wanted to keep it raw," Springsteen says. "I think that's what's slipped out of a lot of modern country music, that certain sort of chill-to-the-bone sound."

As with Joad, many of the songs are set in the Southwest, with Spanish phrases studding the lyrics. "The lives of the new migrant population were interesting stories for me," Springsteen says. "I was just interested in the way the West and the Southwest feel in my imagination."

Springsteen had most of these tunes nearly finished by 1997 but put them aside in favor of a 1999 reunion tour with the E Street Band, which led to 2002's The Rising. The inspiration for reviving the solo material, Springsteen says, was a new song, "Devils and Dust," that he wrote in 2003 at the start of the Iraq War. ("I've got my finger on the trigger/But I don't know who to trust," it begins.) "It is basically a song about a soldier's point of view in Iraq," Springsteen says. "But it kind of opens up to a lot of other interpretations."

Springsteen tried recording the title track as both an angry rock song and an acoustic ballad, but it took the help of producer O'Brien -- who also worked on The Rising -- to bridge the gap. "Brendan found something that put it in the middle, where it picks up a little instrumental beef as it goes," says Springsteen. O'Brien took a similar approach to the rest of the album, helping Springsteen ditch Joad's low-fi sound and minimal arrangements for a more fleshed-out approach.

Among the standout tracks is "Reno," a disquieting ballad about a man's visit to a prostitute -- with an explicit reference to anal sex that won the album an "adult imagery" warning on its back cover. ("It's just what felt right for the song," Springsteen says.) "Long Time Comin'" is an exuberant, rocking love song; "All I'm Thinkin' About" is a buoyant, falsetto-laden lark; and "All the Way Home" is a soul ballad that Springsteen wrote for a 1991 Southside Johnny album, revisited here as a country-rock shuffle.

As he prepared for the Devils tour, Springsteen considered taking a small band on the road. "Nils [Lofgren] and some other folks came in for rehearsals to give me a sense of if I wanted to go with something bigger," he says. "But what tends to be dramatic is either the full band or you onstage by yourself. Playing alone creates a sort of drama and intimacy for the audience: They know it's just them and just you."

The tour -- which hits venues as large as 5,000-seaters -- will focus on the new album, along with material from Joad and 1982's Nebraska, and stripped-down takes on songs from The Rising. "It's not about acoustic versions of my hits -- that's what's not going to happen," says Springsteen, who will also perform on an April 23rd episode of VH1's Storytellers. "I want to forewarn potential ticket buyers: I'm not going to be playing an acoustic version of 'Thunder Road.'"

Springsteen last broke out his hits on last fall's Vote for Change Tour, followed by solo sets at rallies for John Kerry. What did he take away from his stint in partisan politics? "I've tried not to think about it," Springsteen says. "But it was an experience that I'm glad I put myself into. There was a lot of idealism out there -- I took a lot of that with me."

Meanwhile, Springsteen has already written songs that he says could form the basis for another E Street Band album and tour. "I've got some [rock] things, but I haven't heard them back yet," he says. "You've always got to hear them back to know if they're good or not. I'm not sure if it's the very next thing. But I certainly imagine we'll be doing that sooner rather than later."

Bruce Springsteen's initial tour dates:

4/25: Detroit, Fox Theater

4/28: Dallas, Nokia Theater at Grand Prairie

4/30: Phoenix, Glendale Arena

5/2: Los Angeles, Pantages Theater

5/3: Los Angeles, Pantages Theater

5/5: Oakland, CA, Oakland Theater

5/7: Denver, Convention Theater

5/10: St Paul, MN, Xcel Energy Center

5/11: Chicago, Rosemont Theater

5/14: Fairfax, VA, Patriot Center

5/15: Cleveland, OH, CSU Convocation Center

5/17: Philadelphia, Tower Theater

5/19: East Rutherford, NJ, Continental Airlines Arena

5/20: Boston, Orpheum Theater

5/24: Dublin, Ireland, the Point

5/27: London, Royal Albert Hall

5/28: London, Royal Albert Hall

5/30: Brussels, Belgium, Forest National

6/1: Barcelona, Spain, Pavello Olimpic Badalona

6/2: Madrid, Spain, Palacio De Deportes de la Comunidad

6/4: Bologna, Italy, Palamalaguti Arena

6/6: Rome, Italy, Palalottomatica Arena

6/7: Milan, Italy, Milan Forum

6/11: Hamburg, Germany, Color Line Arena

6/12: Berlin, Germany, ICC6/13: Munich, Germany, Olympia Hall

6/15: Frankfurt, Germany, Festhalle

6/16: Dusseldorf, Germany, Phillipshalle

6/19: Rotterdam, Netherlands, Ahoy

6/20: Paris, Bercy

6/22: Copenhagen, Denmark, Forum

6/23: Gothenberg, Sweden, Scandinavium

6/25: Stockholm, Sweden, Hovet

More Bruce Springsteen

Caryn James: Review- Film Series: The World of Christopher Guest

CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK

A Master of Mockery With an Original Touch

By CARYN JAMES

The New York Times

Published: April 8, 2005

n his boutique near Broadway, selling show business memorabilia - big-headed dolls of Brat Pack actors and action figures from "My Dinner With Andre" - the director and choreographer Corky St. Clair, flamboyantly dressed in a red military jacket, pulls out a rare treasure: a "Remains of the Day" lunchbox, with the tragic faces of Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins on the front. "You know, kids don't like eating lunch at school," he says. "But if they've got a 'Remains of the Day' lunchbox, they're a whole lot happier."

Played with deadpan brilliance by Christopher Guest, Corky has no idea he's funny or the least bit detached from reality, even though he spends most of "Waiting for Guffman" putting on a musical pageant in Blaine, Mo., and hoping to take it to Broadway with the original cast, which includes a dentist and two travel agents. That comic approach - precise observations of characters and the gloriously absurd details of their lives, presented without a single wink at the audience - is why "Guffman" and other films written and directed by Mr. Guest are so hilarious.

At 57, Mr. Guest may be the best parodist working today, and the evidence is in a tightly focused retrospective beginning tonight at the Museum of Modern Art.

The series presents his most accomplished films, three recent mock documentaries about characters who are slightly out of the mainstream and either reaching for or sliding away from success: the neurotic, obsessed show-dog owners in "Best in Show"; the balding folk musicians reunited after three decades in "A Mighty Wind"; and of course the would-be Broadway stars appearing in the Blaine school gym in "Guffman."

Other work in the series allows us to see how Mr. Guest's career took shape. There is the hugely influential, now-classic parody of a heavy-metal band, "This Is Spinal Tap," directed by Rob Reiner using an improvisational approach that Mr. Guest later made his own. It's Mr. Guest's character, the literal-minded guitarist, Nigel Tufnel, who famously thinks that creating an amplifier dial that goes to 11 makes the sound louder than 10.

The retrospective also offers Mr. Guest's first film, the conventional Hollywood satire "The Big Picture," and some television work, including sketches from his one year on "Saturday Night Live" that are among that show's funniest, and lesser oddities from the 70's through the 90's. But mostly this series reveals that his three major films are so richly and humanely observed that they can be seen again and again, always evoking laughs in newly discovered places.

A highlight of the series (scheduled for tomorrow) will be an onstage musical performance by Mr. Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer, though it remains their secret whether they will be appearing as their heavy-metal characters from "Spinal Tap," the trio the Folksmen from "A Mighty Wind," or both. The performance will be followed by a conversation with the actors and Parker Posey, who has appeared in the mock documentaries, moderated by Bob Balaban, who has created a series of delightful, tightly wound characters in those films (he's Corky's competition, Blaine High's music teacher, in "Guffman").

That the actors can reunite and sing in character - Spinal Tap has sold out concerts over the years - says everything about the vitality of Mr. Guest's method. Years before unscripted comedies like "Curb Your Enthusiasm," "Fat Actress" and "Unscripted" became trendy, he was creating improvised films around fully realized characters and stories.

For each of the mock documentaries, Mr. Guest and Eugene Levy created the characters and scenes but no dialogue. The actors then improvised so extensively that Mr. Guest ended up with 60 to 80 hours of film, which he shaped into about an hour and a half over months of editing.

There are evident influences on his work, including an enormous debt to the intelligent silliness of Monty Python. But Mr. Guest's films are more improvisational than Robert Altman's and more pointed than Mel Brooks's. He has turned parody - which is, after all, mimicry - into an act of true originality.

Whether you consider "Waiting for Guffman" or "Best in Show" his masterpiece probably depends on whether you're more of a theater person or a dog person. These astute films could be mocking today's reality shows, though the characters are more believable and certainly more entertaining than the people who play themselves on "Survivor" or "The Amazing Race."

As absurd as "Waiting for Guffman" may be, it is built around utterly believable details. The dentist (played by Mr. Levy, indispensable in Guest films) is always called Dr. Pearl, even by his fellow cast members of the musical "Red, White and Blaine." The precision of a novel of manners is juxtaposed with outrageous small touches, like the meek-looking man (never seen again in the film) who auditions for the pageant with an unprintable scene from "Raging Bull."

The humor is never mean-spirited, though; there is warmth behind the creation of absurdly deluded people like Corky.

You can glimpse Corky's roots in the "Saturday Night Live" sketch about a pair of synchronized swimmers, Olympic hopefuls played by Mr. Shearer and Martin Short, whose character wears a life jacket because he can't swim. Mr. Guest directed the sketch and appears as the swimmer's choreographer, who could be Corky's older cousin.

He also directed one of the most enduring and funniest "SNL" sketches ever, in which Eddie Murphy puts on whiteface and discovers that when there are no blacks around, white people get things free in stores and have cocktail parties on New York City buses.

The other television work says more about the timidity of network TV than about Mr. Guest. He appears in and was a writer on a 1975 Lily Tomlin special that has not held up well. More daringly, he wrote for and appeared in an hourlong special (actually an unsold ABC pilot) from 1979 called "The T.V. Show," an "SCTV"-influenced parody of television. "The T.V. Show" is uneven, but it catches the wry satiric spirit of Mr. Guest's work, and it includes one very funny sketch in which Hitler is put on trial in a contemporary court. Hitler is played by Rob Reiner in a powder-blue leisure suit, which adds an extra kitschy layer to the sketch today.

"Spinal Tap" remains wonderfully funny, although it, too, seems like a message from the past now that Ozzy Osbourne has become MTV's domesticated dad. And looking back, the deadpan, not-too-bright Nigel seems the essence of other characters Mr. Guest would go on to play, from Corky to Harlan Pepper, the earnest bloodhound owner and would-be ventriloquist in "Best in Show."

"Spinal Tap" is bookended by "A Mighty Wind" (same players, different music). It was the least well received of the Guest parodies, maybe because "Guffman" and "Best in Show" set the standard so high. "A Mighty Wind" is funny on its own terms, though, and even touching as the one-time lovers and singing team Mitch and Mickey (Mr. Levy and Catherine O'Hara, another essential Guest player) reunite.

Mr. Guest's colleagues can seem so natural on screen that it's easy to undervalue them; that is especially true of Mr. McKean, who has collaborated with Mr. Guest on much of the dead-on music so crucial to the films.

Behind the apparent effortlessness of these films is highly refined comic art. They're convincing, too. Watch any of the Guest parodies and before long the concept of action figures from "My Dinner With Andre" - all that talk, all that smart silliness - can actually make sense.

A Master of Mockery With an Original Touch

By CARYN JAMES

The New York Times

Published: April 8, 2005

n his boutique near Broadway, selling show business memorabilia - big-headed dolls of Brat Pack actors and action figures from "My Dinner With Andre" - the director and choreographer Corky St. Clair, flamboyantly dressed in a red military jacket, pulls out a rare treasure: a "Remains of the Day" lunchbox, with the tragic faces of Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins on the front. "You know, kids don't like eating lunch at school," he says. "But if they've got a 'Remains of the Day' lunchbox, they're a whole lot happier."

Played with deadpan brilliance by Christopher Guest, Corky has no idea he's funny or the least bit detached from reality, even though he spends most of "Waiting for Guffman" putting on a musical pageant in Blaine, Mo., and hoping to take it to Broadway with the original cast, which includes a dentist and two travel agents. That comic approach - precise observations of characters and the gloriously absurd details of their lives, presented without a single wink at the audience - is why "Guffman" and other films written and directed by Mr. Guest are so hilarious.

At 57, Mr. Guest may be the best parodist working today, and the evidence is in a tightly focused retrospective beginning tonight at the Museum of Modern Art.

The series presents his most accomplished films, three recent mock documentaries about characters who are slightly out of the mainstream and either reaching for or sliding away from success: the neurotic, obsessed show-dog owners in "Best in Show"; the balding folk musicians reunited after three decades in "A Mighty Wind"; and of course the would-be Broadway stars appearing in the Blaine school gym in "Guffman."

Other work in the series allows us to see how Mr. Guest's career took shape. There is the hugely influential, now-classic parody of a heavy-metal band, "This Is Spinal Tap," directed by Rob Reiner using an improvisational approach that Mr. Guest later made his own. It's Mr. Guest's character, the literal-minded guitarist, Nigel Tufnel, who famously thinks that creating an amplifier dial that goes to 11 makes the sound louder than 10.