In a gorgeous exhibit, the Prado shines the light on an underappreciated 18th-century genius.

By Brian T. Allen

March 6, 2018

The Choice of a Model

There are two ways to look at the brilliant, comprehensive show the Prado in Madrid is giving Mariano Fortuny (1838–1874). One is redemptive, the other tantalizing and speculative. Fortuny was a brilliant scholarship student from Catalonia who became a superb and famous painter, watercolorist, and etcher. Then, with the market for his work at its hottest, as he became more experimental, he died suddenly in 1874, only 36 years old. Soon, his reputation collapsed. Today, most only know his namesake son, the Venetian textile designer.

How did this happen then? Why fall in love with him now?

Fortuny was an artist’s artist. Young painters as far-flung in style as Vincent Van Gogh, John Singer Sargent, and Thomas Eakins adored his work, as did fellow Catalan Pablo Picasso. For Picasso and his circle, their passion was patriotic but also aesthetic. Artists admired his libertine handling of paint. He painted in big and small dabs and strokes of pure color. He had a childlike attraction to paint as a substance for play, but in his case, play was both intelligent and sensual.

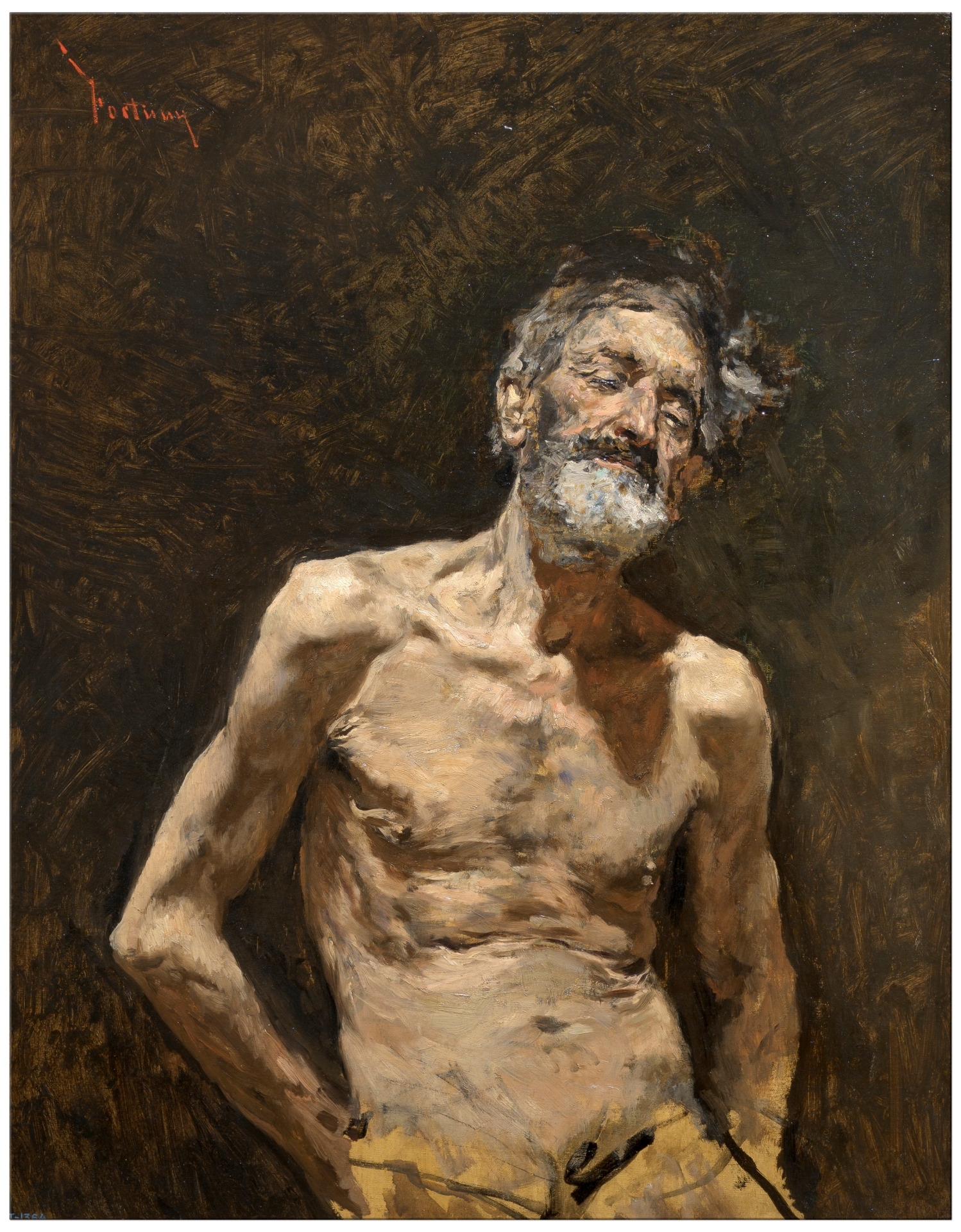

It’s hard to take your eyes off the Prado’s Nude Old Man in the Sun, from 1871.

Though wrinkled and wizened, he absorbs the heat like a sponge, his flesh becoming vibrant and his body limber. The rich, slapdash paint surface enlists all the senses. His eyes are closed, but he isn’t comatose. Ecstasy is closer to the mark. He’s not conventionally beautiful. He’s simply alive, and that is beautiful in itself. Fortuny found him on the street in Granada, stripped him, and painted him against a minimalist, dark background. There’s nothing fancy or fake about him. I can imagine a young artist thinking, “Now, that’s honest painting . . . that’s real.”

How is this picture similar to The Choice of a Model (at top), from around 1870 and lent by the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.?

It’s a period piece, part of the Rococo Revival that started in the 1850s. It’s decadent, even salacious. It’s high-end gaudy. The other is gritty. Though home to the Alhambra and proud of its glorious history, Granada in the 1870s was a dive. Both paintings feature nudes and are frankly carnal. No one is embarrassed, in either picture.

And both pictures sparkle. In each picture, and in all his work, Fortuny worships a surface that glitters. This is very Spanish, descending from the sumptuous clothing worn by kings and queens in portraits by Velázquez and Goya and, further back, to the intricate, flat patterns in Moorish art. In these two pictures, the physical properties of paint and the presence of the artist’s gesture and touch give the figures life. Fortuny “chooses” two very different models, but both feel like flesh and blood.

Why did he disappear from the canon of great artists? Shortly before his death, the first impressionist salon in Paris opened. This single event fomented a radical avant-garde that seemed to go in a different direction from Fortuny’s, though he was actually on a parallel track. Starting around 1870, his subjects are likely to evoke everyday life, not in the modern, bourgeois city or fashionable summer resort, as the impressionists favored, but what he experienced in out-of-style places: Rome, Venice, Granada, Tangiers, and, in his last summer, in Portici, an unglamorous beach town near Naples. He was well on his way toward retiring his period pieces, as much as the market continued to demand them.

The real themes of his late landscapes and sea scenes are light, air, and color and the ways they mold form. The more fascinated with light and color he became, the more time he spent in southern Spain and Morocco. There, dry heat and bright, clear light made the color and texture of both people and things more extreme. Increasingly, he paints in small blocks and cones, much as Cézanne did later. These Fortuny works feel both sensually hot and conceptually cool.

Fortuny was Spanish, and for Spaniards the Islamic world is foreign but familiar. After all, Moorish Spain had a run of 700 years. He depicted many Moroccan scenes and thus suffered from the contempt directed at harem painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose work looked old-fashioned and contrived, technically proficient as it might be. As a Catalan, Fortuny was on the French edge of Spain, geographically and culturally. He was truly international, portable in terms of where he worked, and tuned to everything that was new. One thing he was not was French. It was after the 1870s that the art world’s energy coalesced in Paris and drove advanced taste in Europe and America.

The Prado show is beautifully conceived and paced. It’s chronological except for one gallery devoted to Fortuny’s brilliant etchings, done in the 1860s and 1870s but mostly printed after his death, and another gallery for his massive collection of Islamic and Rococo textiles, metalwork, and ceramics. Its only faults are the absence of an English version of the essential catalogue and the absence of an American or British venue. Having waited 150 years to give Fortuny his big show, the least the Prado could have done was promote a wider book market. American museums own much of Fortuny’s work. Why didn’t one of them demand that the Prado share the show?

In August 1874. weeks before he died, the accomplished, formidable Fortuny wrote, “Now I can paint for myself, the way I like, as I please. . . . It is what gives me the hope of showing myself as I really am.” We’ll never know what this would have meant. In this respect, Fortuny belongs to a group of young artists who died at a most unpropitious time — Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), and, since I have been thinking a lot about the waste of life in the First World War, Franz Marc (1880–1916). Like Fortuny, they had proven genius and were on the cusp of doing their next great thing and giving human creativity a push in a new direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment