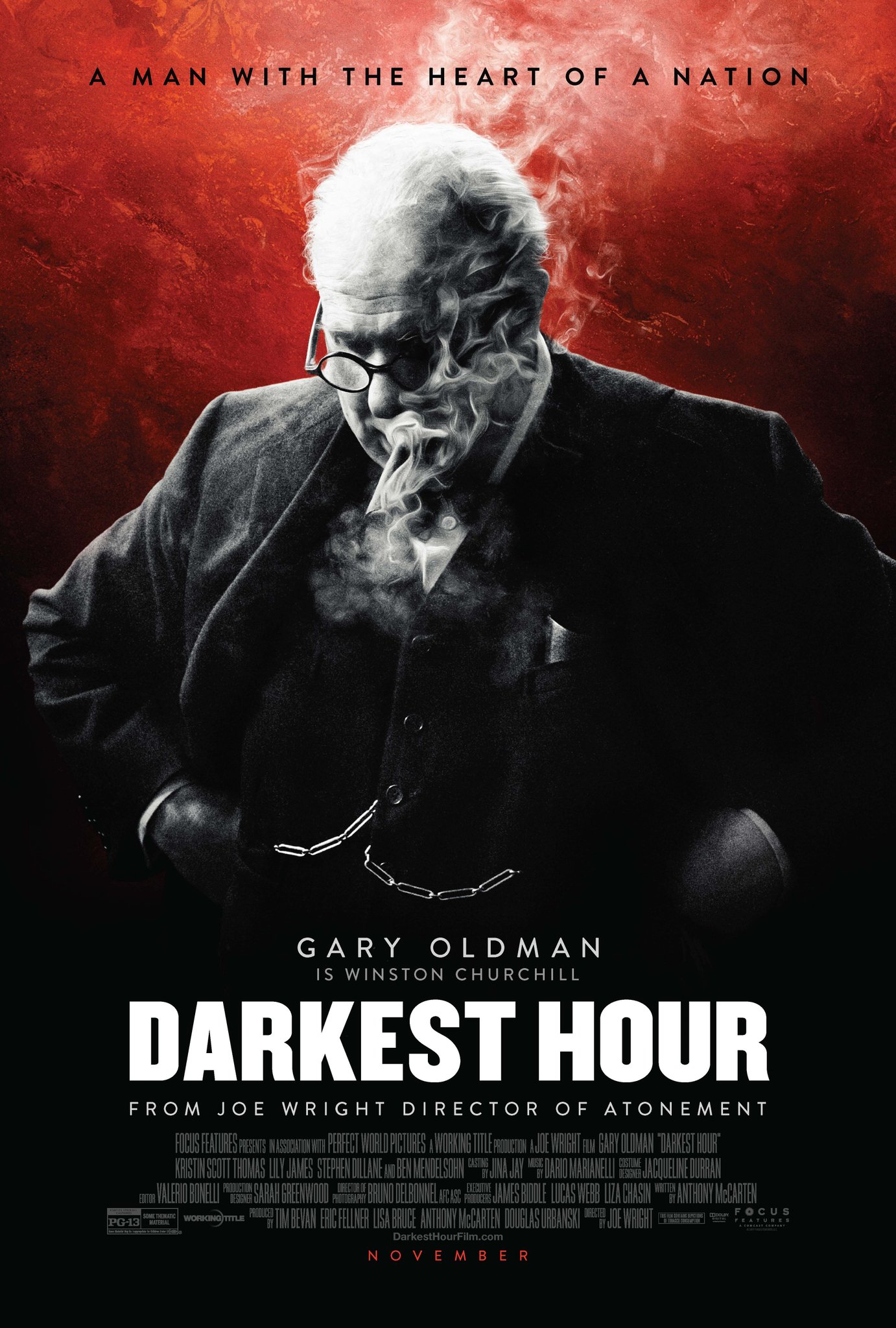

Gary Oldman is a tremendous Winston Churchill in high-octane drama

By Peter Bradshaw

https://www.theguardian.com/film/

13 September 2017

Just as Britain negotiates its inglorious retreat from Europe, and our political classes prepare to ratify the chaotic abandonment of a union intended to prevent another war, there seems to be a renewed appetite for movies about 1940. Christopher Nolan has just given us his operatic immersion in Dunkirk, and now Joe Wright — who himself staged bravura Dunkirk scenes in his 2007 film Atonement — directs this undeniably exciting and beguiling account of Winston Churchill’s darkest hour in 1940, as Hitler’s forces gather across the Channel, poised to invade. It is written by Anthony McCarten, who scripted the recent Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything.

This is not so much a period war movie as a high-octane political thriller: May 1940 as House Of Cards, with the wartime Prime Minister up against a cabal of politicians who want to do him down. It’s interesting for a film to remind us that appeasement as an issue did not vanish the moment that Winston Churchill took over as Prime Minister; despite the famous David Low cartoon, not everyone was right behind him, rolling up their sleeves. Here, his immediate enemies do not seem to be Hitler and Mussolini as much as Chamberlain and Halifax, agitating for a deal with the Nazis and scheming to undermine Churchill’s cabinet and parliamentary position.

They are played respectively by Ronald Pickup and Stephen Dillane, the latter having a malign mandarin impassivity. Dillane makes him a pretty unholy fox. Ben Mendelsohn plays George VI, who is also an appeasement fan at first, though the film gallantly makes him a Churchill convert, conjuring a scene between the two of them in which his job is to stiffen Winston’s sinews. (This film incidentally doesn’t make the mistake in The King’s Speech of implying that Churchill sided with Bertie during the Abdication.)

Darkest Hour has obvious similarities to the recent film Churchill, with Brian Cox; like that drama it imagines a pretty young WAAF figure as his secretary, for him to be at first grumpy and then soppy with - Lily James plays this part here. Miranda Richardson played the exasperated wife Clemmie in the Brian Cox movie and here it’s Kristin Scott Thomas being exasperated and affectionate, helping the impossible old devil dress etc, in more or less the same way - although there’s more here for Scott Thomas to get her teeth into. But this movie packs a much bigger and more effective punch, and that’s down to a more ambitious scale, pacier narrative drive - and the lead performance.

Every time I sit down to another Churchill drama, I promise myself I won’t just roll over for another actor in the latex/Homburg/bowtie/cigar/padding combo and doing the jowl-quivering while speaking in thevoish and the weird cadencesh. And yet there’s no doubt about it, Gary Oldman is terrific as Churchill, conveying the babyishness of his oddly unlined face in repose, the slyness and manipulative good humour, and a weird deadness when he is overtaken with depression. There is a scene (a bit fancifully imagined) with Churchill slumped in a bleakly lit almost unfurnished room, where he looks like something by Lucian Freud. He spends a fair bit of time down in the bunker-ish Cabinet War Rooms yelling at people: these are the “Upfall” scenes, which might get YouTube-subtitled in German in all sorts of irreverent ways. And it is here that Winston reaches his nadir, before the miracle of the little boats has manifested itself. He allows Halifax to send word via the Italians that Britain would be theoretically interested in the Danegeld-price: what might induce Hitler to hold back from Britain and its colonies? Oldman shows Churchill going into a kind of stricken shock.

This is not to say that there isn’t a fair bit of hokum and romantic invention. This film imagines Churchill needing to take a journey on the tube because his official car is held up in traffic. So he meets a quaint cross-section of forelock-tugging British and empire subjects in the underground carriage, from whom he learns something very important — that he is absolutely right!

There is room for a more sceptical movie about Churchill: something revisiting his performance during the Tonypandy Riots or the Siege Of Sidney Street. Or just something that acknowledges that he hated Adolf Hitler for the same reason he hated Mahatma Gandhi: they were both enemies of the British Empire. But Gary Oldman carries off a tremendous performance here, and it’s impossible not to enjoy it. It’s as if his establishment panjandrum George Smiley was suddenly infused with the spirit of Sid Vicious.

An Injustice to Winston Churchill

Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour butchers history to make the British prime minister a much less decisive figure than he actually was.

By Kyle Smith

November 20, 2017

Because an irresolute and small-minded age applies its own neuroses backward to history, because actors love to portray internal torment, and because we fancy ourselves so sophisticated that we know the official story of the past to be a ruse, movies about important historical figures have become less inspiring and “more human,” at times even iconoclastic. In 1988, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ presented a very modern Nazarene wracked with anguish about whether he could carry on with his duty, delivering a casual, vernacular Sermon on the Mount from a dusty slope scarcely more elevated than a pitcher’s mound. The Queen (2006) depicted a matter-of-fact Elizabeth II who fixed car engines. The Iron Lady (2011) approached Margaret Thatcher via the Alzheimer’s disease she suffered in her final years. Lincoln (2012) reconceived the most revered orator in American history as a quizzical figure speaking in a high-pitched, soft rasp.

Now it’s Churchill’s turn to be shrunken down to a more manageable size. In Darkest Hour, which is set across May and June of 1940, the English director Joe Wright and his star Gary Oldman conspire to create a somewhat comical, quavering, and very human prime minister. In dramatic terms it’s an engaging picture, and Oldman is terrifically appealing, but if you’re looking for indecision and angst, the person of Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill is a curious place to declare you’ve found it.

Darkest Hour begins with the resignation of Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup) and Churchill’s accession to the premiership on May 10, 1940, building up to the concluding “We shall fight on the beaches” speech he delivered in the House of Commons on June 4, after the miraculous Dunkirk rescue. (The flight of British forces from the Continent takes place almost entirely offscreen here but has been covered in another movie this year. It also inspired a memorable interlude, captured in one of the most elaborate continuous shots ever put to film, in Wright’s own 2007 movie Atonement).

Introduced to us as a kind of rumpled, absent-minded professor with an alarming predilection for drink and a habit of terrifying his secretary (Lily James), Oldman’s Churchill is alternately funny, disarming, wheedling, and unsettled by events in Europe and Washington, from which in a dismal phone call Franklin Roosevelt is heard informing him that the United States cannot by law come to Britain’s rescue. Churchill insists he must at least have the ships he bought: “We paid for them . . . with the money that we borrowed from you.” Yet Roosevelt’s hands are tied. “Just can’t swing it,” he says. Britain must stand alone.

Such moments capture the sense of a Britain gasping for air as Hitler’s fingers tightened their grip around its neck. But then, in its last half-hour, Darkest Hour veers far off the path of truth. Screenwriter Anthony McCarten has claimed, citing Cabinet minutes, that Churchill’s intentions changed virtually from “hour to hour,” and “this is not something that’s ever been celebrated — that he had doubts, that he was uncertain.” All of this is a gross exaggeration. Churchill told his War Cabinet on May 28 “that every man of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.” I understand the needs of Method actors, but Churchill was not George McFly.

Hectored by a combination of Chamberlain and his fellow appeaser, Foreign Secretary Viscount Halifax (Stephen Dillane), the prime minister is shown as nearly ready to give in and sue for peace through Mussolini. Buckling under pressure, he rediscovers his resolve only because of last-minute pep talks from his wife Clementine (Kristin Scott Thomas) and King George VI (Ben Mendelsohn). The clincher is that traffic halts the premier’s car and he is forced to take the Underground to Parliament.

Wright and screenwriter Anthony McCarten would have us believe that the ghostwriters of the immortal speech to follow were random Londoners Churchill met on that train, where they gave him both courage and some of the actual words he later used. But these events did not occur; the only time Churchill ever rode the Underground was during the general strike of 1926, according to his biographers William Manchester and Paul Reid. To suggest otherwise trivializes Churchill’s defining speech by reducing it to the level of stenography, while completely misstating the direction of wartime inspiration. Churchill was nothing like the people’s puppet. He felt he was born to lead them. As he would later write, “At last I had the authority to give directions over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial. . . . I was sure I should not fail.”

It is a cliché of the motion-picture industry that, in order to sufficiently excite audience interest, the climactic moments must incorporate a reversal of direction. Since we all know how this chapter of World War II ends — to give Wright and McCarten credit, it’s a stirring, magnificent scene in which Churchill rouses the nation with the 34-minute address one MP called “the speech of 1,000 years” — Darkest Hour simply imposes its dramatic needs upon the days preceding it. For the sake of a good yarn, it mistakes a lion for a jellyfish.

READ MORE:

No comments:

Post a Comment