An underrated president emerges from the Roosevelts' shadow

What’s wrong with the Roosevelts? What’s wrong is their shadow. The spotlight of history shines so brightly on Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt that most other presidents, especially conservative presidents, end up in semi-darkness. Whatever these interstitial figures gave the nation gets likewise obscured. While the Roosevelts tapdance across history’s stage, William McKinley, William Howard Taft, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and, of course, Herbert Hoover get locked backstage in a cabinet of “flawed figures.”

What’s more, with each passing year, the Roosevelt shadow deepens. McKinley, especially, is practically forgotten. Sometimes, the obscuring of these presidents is intentional; sometimes half-intentional. Whatever respect President Barack Obama demonstrated to Native Americans when he replaced the title of Alaska’s mighty Mount McKinley with the Native American name, Denali, the president was also doing his bit to intensify the obscurity of non-Roosevelts.

This is a shame, since of course the Roosevelts also featured flaws. And the examples of the non-Roosevelts provide more utility today than do those of many better known executives. The underrating of McKinley, which began while McKinley was still in office, should trouble us especially. (Theodore Roosevelt reportedly said that McKinley had “no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.”) For if the Roosevelts starred in the first half of what is now known as the American Century, that was only because McKinley set that stage for them. The quiet Ohioan served only a little over a term, from 1897 to 1901, when the assassin Leon Czolgosz shot him at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Still, contrary to American national memory, McKinley was a strong president who, whether the area was the economy, the currency, trade, or even America’s role abroad, established trends that ensured our move from isolated continent to world power. You cannot understand American predominance or even the Roosevelts without knowing McKinley.

A tantalizing glimpse of that knowledge was offered by Karl Rove when Rove published his review of McKinley’s presidential campaign in 1896, The Triumph of McKinley (Simon & Schuster, 2016). Now, however, the elusive president comes into full view in President McKinley: Architect of the American Century, a comprehensive and remarkable volume by the editor of this magazine, Robert Merry. In the process of explaining the forces McKinley set in motion, Merry reminds us of more than just the merit of McKinley’s policies. He also suggests that the president does not have to play the thunderer or demi-god. Different styles in the presidency can serve the people well. McKinley never trumpeted from a railcar, as William Jennings Bryan did, and McKinley took his time defining his own visions. McKinley did demonstrate a more subtle kind of leadership that is underrated in politics, though not business, today. That is the leadership of the manager: incremental, opportunistic, and constructive. The thing about McKinley, Merry notes, was that he followed policies, not impulses. McKinley was “a man of perception, who, once that focus has emerged, knew how to formulate the vision and execute it.”

What gave McKinley the qualities that rendered him an excellent president-manager? Experience is the short answer. His youth and middle age provided the equivalent of whole libraries of knowledge of war and government. The son of a foundry operator, McKinley spent his childhood in Ohio, and, at age 18, enlisted together with his cousin, William McKinley Osborne, serving in the Union Army all the way to General Edmund Kirby Smith’s surrender in 1865. First promoted to commissary sergeant, Company E of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, McKinley played a role on the Union side of the bloodiest day of the war, September 17, 1862. The 23rd Ohio found itself pinned down on the far side of Antietam Creek, without food or water. Ignoring orders, McKinley ran a blockade; the back of his carriage was shot away by a cannonball. But McKinley was able to deliver pork, beans, crackers, water, and coffee to the famished soldiers, enabling them, and General George McClellan, to call the day, at least in name, a Union victory. The dutiful, courageous young man caught the eye of Rutherford B. Hayes, who described McKinley as “one of the bravest and finest officers in the Army.” Promoted all the way to captain, then brevet major, McKinley also played a key role in General Philip Sheridan’s rallying of the troops in the Shenandoah Valley, enabling Sheridan to drive General Early and Robert E. Lee out of the valley. In other words, McKinley came to politics with more years of on-the-ground battlefield experience than all the presidents who succeeded him until General Eisenhower.

After reading the law and finishing at Albany Law School, pursuing practice in business areas, and rising under the mentorship of his old acquaintance, Rutherford Hayes, McKinley was elected as a representative for Ohio in 1876. McKinley stayed in Congress for the long haul, rising to the powerful position of House Ways and Means chair, where he acquainted himself with the merits and demerits of tariffs. In those days Republicans did not merely support the tariff, they mythologized it as the best remedy for prosperity. The fact that tariffs were the main source of revenue for federal coffers intensified the myth. The young McKinley avidly supported protectionism. In 1890 he even fathered a tariff, the McKinley Tariff, a mixed bag that raised tariffs in some areas but abolished a tariff on sugar—for the wrong reasons: Washington’s concern that heavy sugar duties would increase the size of the U.S. government by swelling its coffers. Whatever the pretext, the shift pleased Cuban sugar growers. More than 85 percent of Cuban exports went to the United States. But in 1894, Washington then imposed a 40 percent ad valorem tariff on Cuban sugar, leaving beleaguered Cuba to adjust. In Congress, McKinley also learned the ins and outs of district politics. When in 1878 Democrats led a redistricting designed to force McKinley out by a gerrymander, the Ohioan won in his new district nonetheless. McKinley then capped off his career with two terms as governor of Ohio.

Two major issues confronted the nation when McKinley ran for president in 1896. The first was the economy. Though unemployment was not reckoned so precisely in those times, some modern estimates put joblessness of the early 1890s at over 10 percent. Thousands of farms failed, as did thousands of businesses. A share of that failure was due to events abroad. Investors, panicked that they might not be able to redeem their gold from troubled Argentine banks, began to nurse the same doubts about the United States, and pulled gold out of U.S. banks. Seen from Europe, after all, an observer might be forgiven for having trouble distinguishing between the investment potential of the United States and that of Argentina, which with its vast plains and new population of European immigrants boasted both the resources and the know-how to compete with and outgrow the United States. The effect of the gold withdrawal, as well as that of crippling strikes, was to put America into a deep recession. Stock prices moved down, but no one could quantify precisely by how much in the aggregate, so Charles Dow, one of the founders of Dow Jones, pulled together a new index of purely industrial stocks, the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

The American pro-tariff policy, which the candidate McKinley backed unreservedly, was exacerbating trouble at home by raising the prices of foreign goods. The tariff was also, in effect, rendering America provincial: Our defensive posture antagonized other nations and kept the nation from even seeing the potential of international trade. Related was the question of currency. William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate who was McKinley’s opponent, sought to soften the gold standard, which automatically forced monetary contraction when gold left the country. All through the year Bryan coursed across the country arguing that America should not be crucified on a “cross of gold.”

Observers in London or Berlin, by contrast, along with Wall Street, believed that a more dramatic U.S. recovery would come only if the United States reaffirmed its commitment to gold; if gold were always redeemable at American banks, no one would redeem the gold. A solid gold standard would set the United States apart from Argentina and demonstrate that New York was more like London than like Buenos Aires. Uncertainty over the gold standard itself retarded recovery. As an 1896 column in the Wall Street Journal commented: “There can be no reasonable doubt that if people were satisfied that the gold standard would be maintained we should have before us a period of commercial and manufacturing activity and rising prices for securities.”

The second problem McKinley confronted in 1896 was the place of America among older or burgeoning empires: Britain, Spain, Japan. Spanish imperialism was particularly brutal. In Cuba, the Spanish General Valeriano Weyler had declared martial law and was moving thousands of Cubans into fortified towns, called reconcentration centers, and was shooting those who failed to obey. Even after the institution of this dread policy, Spain failed to control rebels and would shortly lose troops it needed in Cuba when they were redeployed to another troubled Spanish possession, the Philippines. In Hawaii, the grandsons of missionaries were perpetually at war with the Hawaiian Royal House, creating a power vacuum. Japan had just invaded Manchuria. Now Tokyo sent the cruiser Naniwa to protect Japanese interests in the islands; it seemed possible the Mikado, as the Japanese emperor was then known, would annex Hawaii.

In the McKinley-Bryan contest of 1896, Bryan played the flamboyant and thus commanded the headlines. Exploiting the new medium of his day, in that case the railroad whistle stop, Bryan reached millions, campaigning to wild acclaim across the country. In Decatur, Illinois, Bryan even rode in a Mueller-Benz automobile, becoming the first candidate to campaign in a car. Meanwhile McKinley stayed home in Canton, Ohio, issuing old-fashioned papers supporting the very forces that seemed to have caused the recent slump: hard currency and big business. Ridiculed as the tool of a handler, his political director and backer Mark Hanna, McKinley nonetheless impressed voters, perhaps because the few speeches McKinley did give rang clear. From his Canton base, McKinley made a practice of playing host to any group that would visit him, a campaign tactic that would later be emulated by Texas governor George W. Bush in Austin. In September 1896, McKinley gave an explanation, Reaganesque in its simplicity, of why a worker would support the plutocrat’s gold standard: He could buy more with a gold dollar. “The laboring men of this country whenever they give one day’s work to their employers, want to be paid in full dollars good anywhere in the world,” McKinley told a delegation of Pennsylvania iron workers. The McKinley arguments inspired a recent college grad, Calvin Coolidge, who argued for the gold standard in a small debate in his hometown of Plymouth Notch, Vermont. Come November, McKinley prevailed.

As president, McKinley at first struck observers as diffident, weak even—Theodore Roosevelt’s éclair comment. The proposals in the president’s early speeches represented compromises: restoring strong tariffs with a nod to free-trade agreements between the United States and individual nations, a strong gold standard at home, but only within the context of a new international agreement on looser bimetallism for leading nations. McKinley and his secretary of state also hesitated on the international front. McKinley told others he was not a “jingo”—he wanted to avoid war with Spain. “I have seen the dead piled up; and I do not want to see another,” he said.

Still, as Merry reveals, the McKinley pauses may have been more intentional timing than cowardice. McKinley knew that the nation did not feel itself entirely recovered from the economic distress of prior years, or clear on foreign intervention; the moment was not ripe for pure, strong stands by the executive.

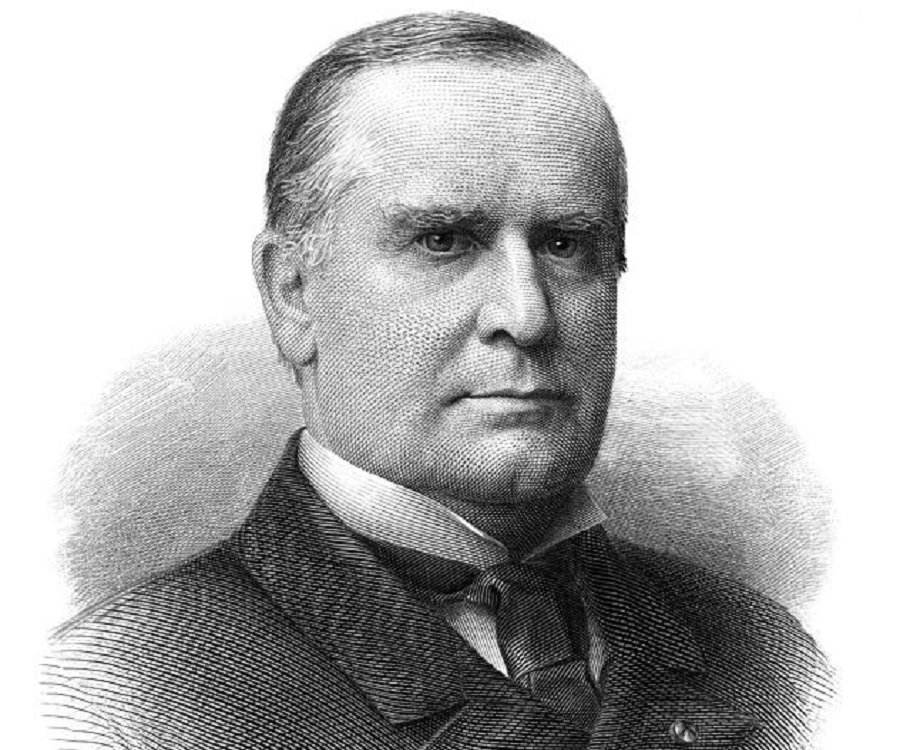

The last portrait of President McKinley, Buffalo, N.Y. Sept. 5, 1901

Sudden catastrophes or foreign crises throw political leaders off balance. Asked by a reporter once what was the toughest challenge in government, Harold Macmillan of Britain replied “Events, dear boy, events.” Yet “events” were where McKinley demonstrated his secret mastery. He knew how to exploit events to strengthen policy. Often, politics might prevent an executive from promulgating a desired policy; but an event might align the desire of the crowd with the plan of the president. The domestic event that provided such an occasion was the expansion of the economy, by some measures more than 10 percent in 1897. McKinley was able, in the midst of such growth, to drop his compromise pose and push a strong gold standard into law. Thus did he ensure that Britain would never mistake the United States for Argentina again.

Sudden catastrophes or foreign crises throw political leaders off balance. Asked by a reporter once what was the toughest challenge in government, Harold Macmillan of Britain replied “Events, dear boy, events.” Yet “events” were where McKinley demonstrated his secret mastery. He knew how to exploit events to strengthen policy. Often, politics might prevent an executive from promulgating a desired policy; but an event might align the desire of the crowd with the plan of the president. The domestic event that provided such an occasion was the expansion of the economy, by some measures more than 10 percent in 1897. McKinley was able, in the midst of such growth, to drop his compromise pose and push a strong gold standard into law. Thus did he ensure that Britain would never mistake the United States for Argentina again.

The news from abroad suggested that neither Cuba nor the Philippines nor even Hawaii would heal themselves. The Spanish abuses in Cuba continued: Cubans were being “torn from their homes, with foul earth, foul air, foul water, and foul food or none,” as Vermont’s Redfield Proctor announced in the Senate. All told, tens of thousands of Cubans would die because of the reconcentration policy. Something had to be done. February 1898 brought the necessary event: the U.S.S. Maineexploded in Havana Harbor, with shards of steel and cement flying in all directions. Hundreds of sailors died. It seemed clear who was to blame: Spain. “WAR! SURE! MAINE DESTROYED BY SPANISH,” shouted William Randolph Hearst’s paper, the Journal. McKinley promptly seized his moment and launched war against Spain. To McKinley, the Maine catastrophe was not the cause of the war; it was an opportunity to find political support for a necessary intervention. Once on the move, he demonstrated breathtaking audacity. In today’s history books Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Rider, owns the section on the Spanish-American war. But it was the affable man from Canton who seized the opportunity and snatched not only Cuba but also the Philippines and Hawaii for the United States. “These things didn’t just happen,” comments Merry. “They happened because McKinley wanted them to happen and because he possessed the political tools to nudge events where he wanted them to go.”

In all his interventions, McKinley, sounding very modern, stressed that his interventions were neutral, that it was not the U.S. intention to colonize these nations but rather to stabilize them. But what did stabilization entail? One component was trade. McKinley was now coming face to face with the greatest Republican hypocrisy, his tariff. One could not pretend to encourage nations to hope for prosperity while barricading oneself against the only thing that could help those nations achieve that prosperity, their exports. Gradually, McKinley began to move towards freer trade. As Richard Nixon had been to Chinese communism—tough—McKinley had been to tariffs. Now, like Nixon, McKinley shifted. The future of the Grand Old Party, but more importantly that of the United States, depended on the United States opening itself to goods. He named a commission to look into digging a canal across Central America; the Commission favored a Panama route.

In short, McKinley’s first term saw him settle on a doctrine that, for good or ill, would become the American doctrine: what Merry describes as “noncolonial imperialism based on unparalleled military and economic power and mixed with an underlying humanitarianism.” The “ill” consequences of noncolonial imperialism we can all enumerate: Cuba going to Castro, the current Middle East. But it’s important to recall there have been good results as well. Had not McKinley, the imperialist, secured Hawaii for the United States, the Japanese might have based an attack on the U.S. mainland from Pearl Harbor rather than attacking Pearl Harbor from Japan. Another example of the benefit of the McKinley doctrine would be Germany. Absent American postwar occupation, and absent our noncolonial formula of imperialism (resetting German governance) and humanitarianism (the Marshall Plan), Germany today would not be the envy destination of every Syrian refugee or the paradigm and leader that it is.

In 1900, the Democrats launched Bryan again, hoping that this time the Nebraskan could beat McKinley. But the country was faring so well that Bryan’s edge was lost: “Four More Years of the Full Dinner Pail” was the Republican slogan, and that dinner pail was full. This time, too, the Grand Old Party enjoyed the advantage of its own energetic campaigner, Theodore Roosevelt; the vice-presidential candidate stumped on the enormously popular Spanish-American war. “Prosperity at Home: Prestige Abroad,” read McKinley’s poster. In those days before the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution, state legislatures selected U.S. senators. Following McKinley’s victory in November three states chose Republicans, giving McKinley a net gain of five in the Senate. In the House, the GOP gained 12 seats, winning a 201-151 majority. With Bryan and populism marginalized, and with the Republican Party united, McKinley looked set: “He is absolutely his own master,” wrote the Chicago Tribune.

McKinley chose the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, to unfold his new trade doctrine. Lit up by the recent advent of alternating current, the exhibition, all shining 350 acres, highlighted the benefits of not just American knowhow but also world knowhow. Here visitors, an international mix of farmers, scientists, diplomats, and American business people, could study a vast array of innovations, including an x-ray machine, the byproduct of the intellect of French scientists Pierre and Marie Curie. All this provided a perfect backdrop for McKinley to declare a new era of friendship among nations and freer trade. The Midwesterner arose and announced, “Isolation is no longer possible or desirable” for the United States. Instead of pure protectionism, the United States must pursue freer trade treaties with individual nations. “Reciprocity treaties are in harmony with the spirit of the times,” McKinley told the crowd. Then, with all the authority of a newly reelected incumbent, McKinley challenged—kicked at—Grand Old Party bedrock. “We must not repose in fancied security that we can forever sell everything and buy little or nothing.”

The line opened up the century for Republicans and the country both. McKinley made clear that the tariff, now lacking the unconditional support of both of the nation’s big parties, was 19th century detritus. That detritus would not easily be cleared: indeed Republicans when they had a chance would lead the nation in imposing new tariffs for the next quarter-century. But detritus the tariff had become still, something viewed generally as regrettable. And of course McKinley was ready to do more. In his second term he aimed to secure the prosperity that had been established in the first. All this was interrupted that afternoon by Czolgosz’s bullet.

Why then doesn’t McKinley hold a prominent spot in national memory? One reason is his imperfection. McKinley did support tariffs, and as such was co-architect of the international downturn of the early 1890s. His use of the Maine incident to launch a war places him, along with Lyndon Johnson and his use of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, or George Bush with chemical weapons in Iraq, into the category of presidents who pushed America into war on the basis of conveniently flawed and incomplete knowledge. For inquiries made from the 1890s on indeed suggested, and then proved conclusively, that the Maine sank not because of Spanish guns but because of an internal explosion.

The larger reason, however, that McKinley is not well-represented can be expressed in that single name: Roosevelt. From the moment he raced down to assume the presidency from a mountain peak, Theodore Roosevelt held the national stage, reminding his colleagues, just 24 hours after McKinley expired, “I am president and shall act in every word and deed precisely as if I and not McKinley had been the candidate for whom the electors cast the vote for president.” TR did not so much manage the presidency as bestride it like a battle horse, or exploit it as a platform—hence the famous TR description of the office as a “bully pulpit.” That McKinley had made possible the Panama Canal project that Roosevelt pursued was soon forgotten, as was the fact that Roosevelt, out of sheer egotism, tore apart the same party that McKinley had so assiduously mended. Roosevelt’s dynamic style—“get action”—captured so much attention as to give McKinley the appearance of being ineffectual. Perhaps the reality is that Americans prefer heroes to managers as presidents. It has been said of Theodore Roosevelt that he always hogged the stage: “Bride at every wedding, corpse at every funeral.” And, one might add, “president in every history.”

That second Roosevelt, Franklin, unwittingly ensured that McKinley would be locked in shadow for another seven decades. That is because of a newer American mythology as strong as the tariff myths in their day: the mythology of the Great Depression. In that mythology, the Great Depression of the 1930s was caused by free markets. And in Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, an active intervention gets elevated as salvation, and a more traditional course, Coolidge-style lower taxes and McKinley tight money, are correspondingly demonized.

This is a loss, not merely because of the value of policies, but also for the value of presidential style. Today both parties insist on “getting action,” as Theodore Roosevelt did, rather than exhibiting restraint. This despite the fact that restraint can often serve the country better. Those who do not leap into foreign conflicts might take note of the fact that Calvin Coolidge made non-intervention, even in civil-rights-abusing butchery such as Mexico’s Cristero conflict, arguable. At home, there are also lessons. Bernie Sanders followers would allow that entitlement cut-backs are necessary, their only quarrel being as to where the knife will be applied. Part of the problem, for all parties, is that touching entitlements is deemed politically impossible. Yet several of these obscure presidents cut budgets and at least one, Coolidge, won an election afterward.

Even if we cannot approve of every move made by presidents less known than the Roosevelts, knowledge of those moves is necessary. Merry’s President McKinley is a necessary contribution to a necessary campaign on the battlefield of history. What Merry says of McKinley’s critics holds true for the critics of so many presidents: “They insisted on judging him as unequal to his deeds.”

Amity Shlaes, chairman of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, is the author of Coolidge and The Forgotten Man. A presidential scholar at the King’s College, she is at work on a new history of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment