Young Freud, cruel, incurious, deceptive, and in search of fame

By Matthew Hutson

September 1, 2017

Mention Freud and you’ll get some strong reactions. He’s known as a spelunker of the human soul, responsible for uncovering such veins of frisson as denial and projection, but also for questionable or damaging contributions such as penis envy and the Oedipus complex.

An informal poll of my peers I recently conducted on Facebook revealed his mixed reputation. One respondent said: “Brilliant and interesting philosopher of mind.” Another: “Gut response, mostly wrong about everything.” There was this accolade: “I don’t think you can look at the field of psychology without seeing him as a giant.” And this attack: “A horrible misogynist.” . . . Oh, and this: “Plus he was a real drug user, which is fun.”

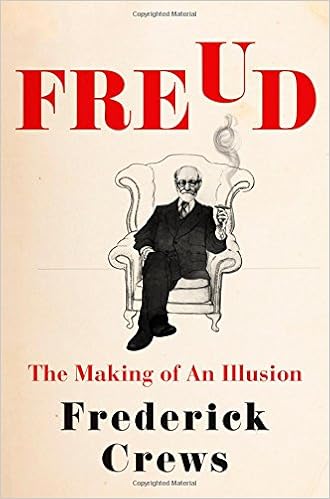

In a new biography, “Freud: The Making of an Illusion,” Frederick Crews depicts his subject as cruel, incurious, deceptive, and both fragile and vainglorious. Crews focuses on Freud’s early career, from 1884 to 1900, and the picture that emerges is of a trumped-up blowhard.

Freud’s life has been digested and redigested for decades, but Crews, an English professor and former psychoanalysis advocate, takes on this period because he says it’s been overlooked except by proselytizing partisans who distort the record. Plus, the complete set of Freud’s letters from this period to his fiance, Martha Bernays, has recently been released.

The driving force of the narrative is Freud’s yearning to become famous — for anything. In school, he was keenest on philosophy and entered medicine not out of interest or aptitude but for a living. His first stab at notoriety came with a useless cell-staining method he overhyped in scientific papers Crews describes as “crass propaganda.”

Next he turned to cocaine, which he expounded as a cure-all (and habitually injected). Freud tried to treat his friend’s morphine addiction with cocaine, rendering him doubly addicted, then fraudulently championed the fiasco as a string of successes with multiple patients. He even sold fake data to a cocaine manufacturer and pseudonymously published an academic article praising his own work.

Freud’s engagement with psychotherapy began in 1885 on an extended visit to a Parisian hospital. There he witnessed the treatment of “hysteria,” a grab bag of physical and psychological symptoms thought to be psychogenic — and distinctly feminine — and he took note of hypnosis as a method of inquiry. Essentially, the staff would knowingly or unknowingly induce women to act out, and punish them if they didn’t, using sedatives or clitoral cauterization. Apparently, Freud liked what he saw. He returned to Vienna and opened up shop.

Far from a passive listener, he insisted that patients had been sexually abused as children, and if they failed to recall anything, he would describe the episodes in detail. Many patients went away fuming — or laughing.

Freud’s claims skirted falsifiability, the quality of being testable, a bedrock of the scientific method. Resistance to his lurid suggestions, he argued, meant only that he was onto something; heads I win, tails you really do want to fellate your father. He also conspired to excommunicate any analyst from the movement who dared to subject his ideas to critical scrutiny. As Freud wrote to a close colleague, he was only “fantasizing, interpreting, and guessing” toward “bold but beautiful revelations.” He claimed: “I am actually not at all a man of science, not an observer, not an experimenter, not a thinker. I am by temperament nothing but a conquistador.”

As a result, he made claims about humanity based not on the evidence his patients presented but on hunches about his own hang-ups. He was apparently ashamed of his bisexuality, his masturbation and his molestation of his sister.

His ideas about sex and gender curdled his marriage to Martha. In letters, he called her unskilled, unpretty and deficient in personality. She asked for “a little respect.” He wrote, “If I have become unbearable recently, just ask yourself what made me so.” He tried to turn her against her mother, brother and friends — his rivals. After she bore him six children, he invited her sister to move in. Crews says Freud and his sister-in-law became secret lovers (she nearly died aborting his child), and he treated his wife as a maid and nanny.

Freud was not only a misogynist but also a misanthrope. He wrote a colleague: “I have found little that is ‘good’ about human beings on the whole. In my experience, most of them are trash.” He especially looked down on his patients. He told one colleague: “Patients only serve to provide us with a livelihood and material to learn from. We certainly cannot help them.” He surprised another colleague with this about his patients: “I could throttle every one of them.” The families of his (usually rich) clients called him a con man.

So Freud failed to help people, but his ideas have lasted, right? Turns out, for the most part they weren’t even his. He took the words “the unconscious” and “psychoanalysis” from his rival Pierre Janet’s “subconscious” and “psychological analysis,” describing ideas that go back much further. Throughout his career, Freud reliably rode his mentors’ coattails, then stabbed them in the back when they could carry him no further, publicly deriding them or erasing them from history.

One might wonder, then, about the origin of his appeal. His reputation comes not despite his profligate scholarship but because of it. He trumpeted his failures as successes, turned wild speculation into sweeping proclamation and, starting with 1899’s “The Interpretation of Dreams,” produced what Crews calls “detective fiction” rather than clinical reports. Crews writes: “Freud would truly be breaking new ground in the ‘Interpretation,’ not as a scientist but as a literary artist.” Freud was a fan of Sherlock Holmes mysteries, and Crews notes that a later case study provided an “invitation to the reader to share in forensic work that was both intellectually and sexually thrilling.”

In spreading word about the unconscious, despite offering some harmful ideas about it — calling gays perverts, masturbators evil and women conniving — did Freud incidentally help humanity? Crews doesn’t spend much time on legacy, except to suggest that Freud’s distraction from real scientific and therapeutic work set psychology and neuroscience back by decades.

The book can be rough going in some places, through no fault of the dedicated author. Rather the source material eschews penetrability and plausibility; Freud’s accounts became so tangled over the years as he avoided admitting error that I fear there’s no untangling them. Even so, “Freud” is a surprisingly fun read, as Crews gets in plenty of sharp jabs. He seems to find the most damning way to spin any admission or incident, leaving one to wonder about his own interpretive filters. Still, given the facts presented, it’s hard to imagine additional disclosures that would completely reverse the overall impression.

The notion of Freud as a great explorer, albeit with a wonky compass, persists. He’s shorthand for buried memories and impulses. Perhaps we’d be better off if his own buried treasure had stayed buried. Sometimes a fallacy is just a fallacy.

The Curious Conundrum of Freud’s Persistent Influence

By George Prochnik

August 14, 2017

Frederick Crews, the eminent literary critic and perennial Freud censor, opens his new study with an important question: “If Freud’s career and its impact are so well understood, what justification could there be for another lengthy biographical tract?” This question is especially pertinent since, as Crews goes on to note, Freud’s scientific reputation has plummeted over the past generation. Medical authorities have broadly recognized the faulty empirical scaffolding of psychoanalysis and its reliance on outmoded biological models. Mainstream American psychologists moved on decades ago.

Yet, confoundingly, Freud “is destined to remain among us as the most influential of 20th-century sages,” Crews writes, claiming that the attention bestowed on him by contemporary scholars and commentators ranks with that accorded Shakespeare and Jesus. Here is a fascinating conundrum: The creator of a scientifically delegitimized blueprint of the human mind and of a largely discontinued psychotherapeutic discipline retains the cultural capital of history’s greatest playwright and the erstwhile Son of God.

Crews is right that the matter demands further investigation, but this is not the book he has written. Instead “Freud: The Making of an Illusion” focuses on the man — specifically how a reflective young scientist with high ambitions and gifted mentors lost perspective on his “wild hunches,” covered up his errors and created “an international cult of personality.” In practice, this translates into 700-plus pages of Freud mangling experiments, shafting loved ones, friends, teachers, colleagues, patients and ultimately, God help us, swindling humanity at large. Here we have Freud the liar, cheat, incestuous child molester, woman hater, money-worshiper, chronic plagiarizer and all-around nasty nut job. This Freud doesn’t really develop, he just builds a rap sheet.

There is value in Crews’s having synthesized the full roster of Freud’s blunders between 1884 and 1900, the period his book concentrates on. Almost all of this material has been covered before, but not compiled in one volume — and Crews has brought a new level of detail to some of these accounts. He offers a lengthy review of Freud’s harmful embrace of cocaine’s efficacy as a local anesthetic, a mistake compounded by his paid endorsement of its merits for a pharmaceutical company. Crews tells the story of Freud’s apprenticeship with the renowned French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who became known as “the Napoleon of the névroses,” and whose theories of psychologically traumatic hysteria, though arrived at largely through scientifically dubious hypnosis-based research, heavily influenced Freud’s understanding of the syndrome that loomed large in the history of psychoanalysis. We have extensive recapitulations of the distortions Freud introduced into his early case histories — most famously in the case of Dora. Crews’s exceptional fluency in the source material allows him to integrate complex incidents into an impressively cohesive narrative.

The usefulness of the aggregation would have been greater had Crews presented his story with more of that objectivity he finds so damningly absent in Freud. Here, “Freud outdid himself in thickheadedness.” There we encounter the “apogee of Freud’s willful blindness.” Elsewhere we read of Freud indulging his “yen for borrowed power,” and exhibiting “madcap self-deception.” Some of the slanting is more subtle. Crews seeks to demonstrate that Freud, for the sake of self-mythologizing, exaggerated his sense of being treated as an inferior and an outsider at the University of Vienna because of his Jewishness. This is not a minor point since, as Adam Phillips argues persuasively in “Becoming Freud: The Making of a Psychoanalyst,” psychoanalysis can be understood as a psychology “of, and for, immigrants,” people “traumatized by sociability … whose desires don’t easily fit into the world as she finds it.” Crews tells us that of Freud’s Jewish peers at the university, most others “appear to have felt at home there,” though he provides no indication of where he has discovered this significant data point. In fact, one of the most credible works to explore the subject, which Crews himself draws on, reports that in the year Freud enrolled, tensions between Jews and the gentile majority were palpable, with anti-Semitism against Jews from Galicia, where Freud’s family originated, particularly acute. Crews also cites a letter in which Freud describes the “academic happiness” he experienced on campus, “which mostly derives from the realization that one is close to the source from which science springs at its purest.” Crews comments, “If Freud had been met with ostracism on entering the university, he surely would have wanted to end the ordeal as speedily as possible.” But Freud would hardly be the first young person to encounter an atmosphere of alienating racial prejudice on an academic campus that was yet counterweighed by the opportunity to slake an intense thirst for knowledge.

Later, in taking Freud to task for an overly mechanical view of mental events in general and sexual excitation in particular, Crews avers that Freud’s preoccupations prevented him from understanding that “positive sexual experience is a function not just of secretions, agitated tissues and discharges but of whole persons whose need to feel respected is fulfilled in the encounter” — an understanding, Crews says, which “the rest of humanity intuitively knows.” We might speak of the conjunction of respect and sex as a communicable ethical ideal within certain cultures. But the available evidence from those densely populated societies that overtly oppress women — or within the campus frat world here at home — would suggest that much of humanity tends, if anything, to intuitively separaterespect from sexual gratification.

This selective idealization of humanity gets at a deeper problem. Crews is so invested in denying Freud primacy for any of the ideas associated with psychoanalysis that have retained a jot of credibility, and offers such a paucity of larger sociohistorical context for a study of this scale, that in reading his account it is easy to imagine humanity’s understanding of sexuality and psychology as such was advancing quite admirably until Freud came along and thrust us all into the lurid dungeon of his own ugly obsessions. Stefan Zweig’s account of sexual life in pre-Freud Vienna provides a different perspective: “The fear of everything physical and natural dominated the whole people, from the highest to the lowest with the violence of an actual neurosis,” Zweig wrote in his autobiography. Young women “were hermetically locked up under the control of the family, hindered in their free bodily as well as intellectual development. The young men were forced to secrecy and reticence by a morality which fundamentally no one believed or obeyed.” The cruelty of this social paradigm was equally pernicious across the Atlantic, contemporary observers noted, where New England’s code of civilized mores was often crippling for women and morbidly confusing for men.

By identifying sexual desire as a universal drive with endlessly idiosyncratic objects determined by individual experiences and memories, Freud, more than anyone, not only made it possible to see female desire as a force no less powerful or valid than male desire; he made all the variants of sexual proclivity dance along a shared erotic continuum. In doing so, Freud articulated basic conceptual premises that reduced the sway of experts who attributed diverse sexual urges to hereditary degeneration or criminal pathology. His work has allowed many people to feel less isolated and freakish in their deepest cravings and fears.

Crews is correct that many of Freud’s ideas were prefigured in the findings of others. But has this ever not been the case with a paradigm-transforming figure? Freud created a language in which key insights could be broadly transmitted to the culture: “a whole climate of opinion/under whom we conduct our different lives,” in Auden’s formulation. Even at the time Freud’s writings were appearing and psychoanalysis was in the ascendancy, most people understood that one did not have to embrace the whole gospel to reap worthwhile insights. Indeed, as Crews repeatedly demonstrates, Freud contradicts himself enough that no monolithic psychoanalytic theory ever existed.

How much less today are we bound to the kind of binary choice this book implies we must make, between counting ourselves among the believers in the “illusion” of Freud or as enlightened adversaries to every manifestation of Freudian thought? Where to even begin enumerating the wealth of fruitful work — some of it highly critical — that continues to emerge from real engagement with Freud’s ideas? Consider Marina Warner’s musings on Freud’s mediation of Eastern and Western cultural tropes told through the story of his Oriental carpet-draped couch; Rubén Gallo’s panoramic exploration of the reception of Freud’s work in Mexico and the reciprocal influence of Mexican culture on Freud; and the rich medley of sociopolitical critiques grounded in Lacan’s reinterpretation of Freud’s thought.

The idea that large parts of our mental life remain obscure or even entirely mysterious to us; that we benefit from attending to the influence of these depths upon our surface selves, our behaviors, language, dreams and fantasies; that we can sometimes be consumed by our childhood familial roles and even find ourselves re-enacting them as adults; that our sexuality might be as ambiguous and multifaceted as our compendious emotional beings and individual histories — these core conceits, in the forms they circulate among us, are indebted to Freud’s writings. Now that we’ve effectively expelled Freud from the therapeutic clinic, have we become less neurotic? With that baneful “illusion” gone, and with all our psychopharmaceuticals and empirically grounded cognitive therapy techniques firmly in place, can we assert that we’ve advanced toward some more rational state of mental health than that enjoyed by our forebears in the heyday of analysis? Indeed, with a commander in chief who often seems to act entirely out of the depths of a dark unconscious, we might all do better to read more, not less, of Freud.

Crews has been debunking Freud’s scientific pretensions for decades now; and it seems fair to ask what keeps driving him back to stab the corpse again. He may give a hint at the opening of this book, when he confesses that he too participated in the “episode of mass infatuation” with psychoanalysis that swept the country 50 years ago. The wholesale denigration of its founder is what we might expect in response to a personal betrayal of the highest order, such as only an idol can deliver. Paraphrasing Voltaire, if Freud didn’t exist, Frederick Crews would have had to invent him. In showing us a relentlessly self-interested and interminably mistaken Freud, it might be said he’s done just that.

No comments:

Post a Comment