By Jerry Harkavy, The Associated Press

September 18, 2017

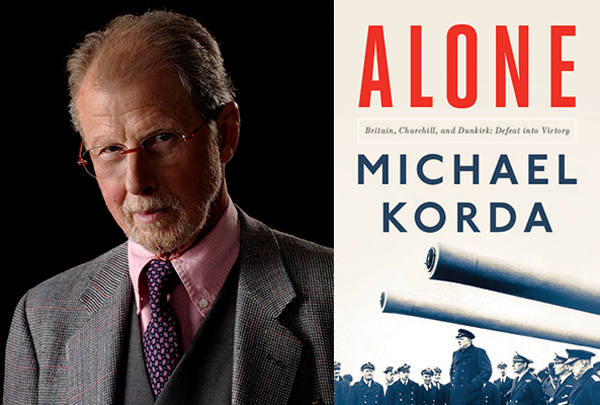

Interest in the 1940 cross-channel evacuation of British soldiers amid the French collapse in World War II has sprung to life this summer, thanks to Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster movie “Dunkirk.” On its heels comes “Alone,” Michael Korda’s masterful account of that epic drama and its impact on his family.

Few of the soldiers, airmen and mariners whose heroism allowed Britain to carry on a singlehanded battle against Nazi Germany are alive today. Korda was only 6 years old at the time, living in London with his filmmaking family whose roots were in central Europe. But he was remarkably aware of events that propelled Europe into war.

Korda recounts how he and his family had to cut short their August vacation in France as war clouds thickened in the weeks prior to Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland. They were glued to the radio for Neville Chamberlain’s grim announcement that Britain was at war. The author recalls air raid sirens, the family’s temporary move to the countryside and his evacuation to a farm in Yorkshire followed by his stay at a boarding school on the Isle of Wight before his return to London.

Korda’s family was moviemaking royalty. His uncle, Alexander, was a renowned producer and director, married to actress Merle Oberon, and his father, Vincent, was a film art director. When war broke out, the family production company, London Films, was in the midst of one of its most ambitious projects, the Arabian fantasy movie “The Thief of Bagdad.”

“Alone” describes in detail the tense political drama that surrounded the emergence of Winston Churchill as prime minister just hours before Germany invaded France and the Low Countries. Alex was a longtime friend and supporter of Churchill, who gave his blessing to the producer’s decision to move his operation to Hollywood after wartime manpower demands made it impossible to finish his films in England.

The trans-Atlantic move had the British government’s clandestine blessing and financial support in hopes that Alex’s subsequent film “That Hamilton Woman,” about Admiral Horatio Nelson and his mistress, would build pro-British sentiment in the United States.

Family issues highlight some of the more fascinating dynamics in “Alone,” but the book is first and foremost a riveting account of the fate of the 300,000-man British Expeditionary Force during its retreat toward the English Channel as German tanks overran Belgium and set their sights on Paris in a blitzkrieg that left France demoralized and prey to a wave of defeatism and recriminations.

Illuminating profiles of key players include those of Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, architect of the evacuation plan dubbed Operation Dynamo; German tank warfare strategist Heinz Guderian; and a string of hapless French generals. On the political side, we meet the British appeasers whose lapses in judgment paved the way for Churchill — described by Korda as “that rarest of men, a well-functioning, even hyper-functioning alcoholic” — to rally his people to ultimate victory.

Perhaps the biggest question that Korda and other historians have struggled to address is why the Germans temporarily halted their race to the channel, a decision that allowed Britain to assemble a fleet that ranged from Royal Navy destroyers and commercial ferries to fishing boats and yachts, enabling its troops to survive and fight another day.

Some suggest that Hitler chose to spare the British army as a sign of his good intentions and encourage a peace settlement. For his part, Korda believes the three-day rest break was designed to prepare the panzer divisions for the decisive encounter with the French army while delaying an advance in the marshy terrain of Flanders.

“Alone” reaches its climax in the days depicted in Nolan’s film. The author’s descriptions of fire and smoke along with smells of burning rubber and unburied bodies evoke images as vivid as any to hit the screen. One writer quoted by Korda likens it to “a scene from Dante’s Inferno.”

Korda likens the evacuation to a big lottery. “Some people went to the beach, fell into the right line, were taken aboard a ship with a minimum of drama, and disembarked a few hours later at Dover.” Others were shelled while on the beach, machine-gunned by German aircraft or drowned when their ship was mined, bombed or torpedoed.

A total of 338,226 troops, including 139,921 French, made it to England, but it was only months later — after the Battle of Britain — that fears of invasion dissipated and the “spirit of Dunkirk” became cause for celebration. It was, according to Korda, “that rarest of historical events, a military defeat with a happy ending.”

It is rare and fortuitous that this spellbinding account came out within weeks of the release of Nolan’s film that struck box-office gold. One can only hope that many of those drawn to the movie will go on to read “Alone” to delve further into the details and context of that historic episode.

You saw the movie; now get the whole story of Dunkirk in Michael Korda;s 'Alone'

By David Walton

September 18, 2017

Alone, Michael Korda's page-turning history of the British army's evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940, has the good fortune — or possibly misfortune — of appearing soon after Christopher Nolan's blockbuster film on the same subject.

Film may be a better medium for visual reproduction, for instance, in depicting the layout of Dunkirk harbor — a crucial feature that prevented a large-scale evacuation and created the imperative of a civilian rescue, thus rallying the resources and fighting spirit of the British people, and redirecting the course of the war.

That's the story both film and history tell. But as readers of history know, every great event has its short version and its long, its concise legend and its more untidy set of truths. Why didn't the Germans take Dunkirk when they could have — surround the British, and massacre or imprison them as they did 2 million of the French?

Nolan's two hours of screen time are a powerful re-enactment, but they cover only the final 100 of Korda's 400 pages. Alone begins in September 1939, with the author's first memory, from the age of 7, of Britons fleeing the continent after war has been declared.

"It is curious with what clarity one remembers great events of the past," Korda recalls, as he pieces through the unfolding events of the next nine months. Uncle Alexander Korda, the family head, is Britain's leading filmmaker, commissioned by Churchill to advance Britain's cause by making high-quality pictures. His wife, "Auntie Merle," actress Merle Oberon, is fresh from her success in Wuthering Heights, and eager to return to Hollywood. Father Vincent is working on Thief of Baghdad, the film that will earn him an Academy Award for set design in 1940.

From this privileged vantage point, the Kordas know more than most about the worsening situation on the Continent — news kept from the British public until the very last.

This is a book you won't want to put down. Korda is a graceful and personable writer, well-informed, perceptive, always to the point. Step by step, he traces the long chain of blunders, misunderstandings, and entrenched prejudices that led to defeat on the battlefield. France and Britain had prepared for a defensive war, expecting to fight on fixed lines as in World War I. The Germans prepared for an aggressive mobile war, spearheaded by high-speed tanks that would cut defensive lines and keep advancing.

Neither France nor Britain fully liked or trusted each other. It was rare, Korda remarks, for a British officer to speak French, and many British disdained the French soldiers' slovenliness and lack of discipline.

France, in turn, felt dragged into the war by Britain, first into the Czech crisis, then in Poland. Repeatedly, Britain and especially Churchill overestimated France's ability and willingness to fight, while the French bitterly resented Britain's unwillingness to supply more troops and, in particular, to provide air cover — "a sensible decision," says Korda, that "would prove decisive during the Battle of Britain, which began two months later."

Why did the Germans hold back? Again, the reasons are complicated. They feared their line was overextended, and they were in danger of being cut off, as happened at the Marne in World War I. And, following an old tradition of cavalry advances, they felt they needed to "rest" their mounts.

Germany's early victories and rapid advance led, paradoxically, to doubt and caution. For Hitler and the German high command, France was the primary target, and neither Germany nor Britain fully gauged how disorganized and beaten the French were.

At the same time, the German army "was not prepared for the stout resistance of a foe they thought had already been defeated." Hard-pressed British units mounted a fierce counterattack against Hitler's best troops at Arres, sending alarm up the German chain of command. For five crucial days, British fighters held a thin line of defense around Dunkirk that the Germans somehow never penetrated — "a remarkable feat of arms," Korda writes.

The "Miracle of Dunkirk" he credits to "a natural element of naval professionalism" embodied in Vice Adm. Bertram Ramsay, commander of Dover operations. As a matter of routine, Ramsay began registering available craft and planning evacuation routes, even as British troops were setting out for the Continent.

When the moment came, Ramsay assembled within three days a fleet of more than 800 vessels, and of the 400,000 stranded at Dunkirk, evacuated 338,226, of whom 139,921 were French.

Alone is the compelling story, told in illuminating detail and without the Imax din, of how they got there, and how they got away.

David Walton writes and teaches in Pittsburgh.

No comments:

Post a Comment