By Nathaniel Blake

https://thefederalist.com/2019/07/12/justice-trial-definitive-account-brett-kavanaughs-confirmation/

July 12, 2019

Brett Kavanaugh, Christine Blasey Ford

Brett Kavanaugh, Christine Blasey Ford

“Justice on Trial” is a political thriller about sex, power, and lawyers. In this excellent book, Mollie Hemingway of The Federalist and Carrie Severino of the Judicial Crisis Network have provided the definitive account of Brett Kavanaugh’s ascent to the Supreme Court.

Both authors were part of the confirmation battle. In addition to her work at The Federalist, Hemingway is a regular on Fox News. Severino’s group supported Kavanaugh with millions of dollars in advertising. Following his confirmation, the authors interviewed more than 100 crucial actors in this political drama, including the president, Supreme Court justices, high-ranking officials, and dozens of senators.

Thus, although the basics of the Kavanaugh confirmation fight will be familiar to readers, this skillful retelling provides many more details about everything from the selection process to Kavanaugh formally taking his place on the Supreme Court. Hemingway and Severino tell their story in crisp prose while deftly deploying detail and humor to punctuate and enliven the narrative.

The Drama and the History

The madness of the confirmation process is illustrated by a multitude of anecdotes, from the Kavanaugh family having to stash luggage in a neighbor’s treehouse as they avoided the press, to the spectacle of a protestor wandering Capitol Hill “dressed as a giant condom.”

But this book is not just about the drama of one judge’s nomination and accusations against him of youthful sexual misconduct. The authors adroitly place the story in context, situating it amidst both recent events such as the Trump campaign and the Neil Gorsuch nomination, and broader political and legal history, including the excesses of the Warren court and the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings.

Like the Thomas hearings, this attempt to scuttle a Supreme Court nominee was a defense of a judicial coup that redistributed power in defiance of the Constitution’s design of a government of limited and enumerated powers. For much of the last century, the federal courts were complicit in the unconstitutional expansion of centralized government power in the administrative state.

The courts also seized enormous power for themselves, deciding policy on a host of contentious political issues such as abortion. The Supreme Court became “the forum where philosopher kings impose the final decision in our most divisive political and social disputes.”

Crux: The Invented Right to Abortion

“Justice on Trial” lays out the history of conservative disappointment with Republican judicial appointments, including Anthony Kennedy. Despite past failures, conservatives hoped Kavanaugh would solidify an originalist majority on the Supreme Court that would work to restore the legitimate constitutional order.

But Democrats were terrified at this prospect, especially as regards Roe v. Wade, which invented a constitutional right to abortion. Sen. Diane Feinstein opened the Democrats’ remarks at the initial hearings by “declaring that the confirmation battle was about abortion.”

Thus, the Kavanaugh fight was never just about his purported sexual misdeeds, but about the entire sexual culture that depends on abortion on demand. Ironically, the crude, abusive sexual culture that Kavanaugh was accused of participating in as a young man in the 1980s was enabled by the very decision his opponents most feared he would overturn.

This fear induced some Democrats to declare their opposition to Kavanaugh before he was even nominated, with many more joining in immediately after the announcement. Hemingway and Severino remind readers how Democrats turned the initial hearings into a circus with endless interruptions, costumed protestors, and Sen. Cory Booker trying and failing to have a “Spartacus moment.” Nonetheless, Kavanaugh seemed assured of confirmation.

Then the Democrats and their media allies released their secret weapon: an accusation of high school sexual assault that they had held in reserve for weeks.

If We Can’t Get Him One Way, We’ll Get Him Another

All hell broke loose, and “Justice on Trial” provides readers the inside scoop on how Republicans responded and triumphed. Most importantly, the confirmation team believed the judge’s denial of any wrongdoing. Trump did not waver in his support for the judge, and the president’s team encouraged Kavanaugh to fight back.

They refrained from attacking accuser Christine Blasey Ford personally—they did not publicize her own alcohol-fueled escapades “in high school and college,” which were “dramatically at odds with her presentation in the media”—but they aggressively disputed her claims, and Kavanaugh “wanted a public hearing to clear his name.”

While Ford’s lawyers and the Democrats stalled, Kavanaugh was attacked with additional accusations. The media, drunk on the prospect of the Me Too movement toppling a Trump Supreme Court pick, hyped every new allegation. But unlike other Me Too cases, each new charge was less believable. The Democrats and their allies sought to establish a pattern of sexual misconduct by Kavanaugh, but the pattern they actually demonstrated was their willingness to promote any story, no matter how outlandish, to stop his nomination.

After Ford and Kavanaugh finally testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Democrats leaned on Republican Sen. Jeff Flake and dramatically secured a delay for a new round of FBI interviews. This “frustrated Kavanaugh’s supporters, but the investigation turned out to be a godsend.” By the end of that weeklong effort, “each of the three main allegations against him was crumbling.” Reviewing the claims against him emphasizes that they ranged from implausible to insane.

A Herd of Unproven Allegations

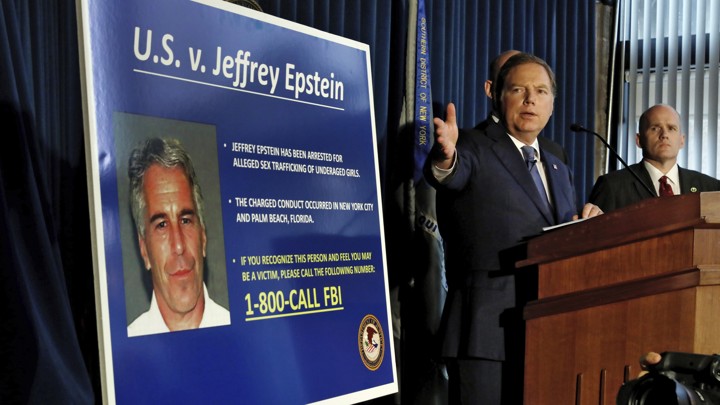

Julie Swetnick’s lurid tales of high-school gang rape were “obviously ridiculous,” and her lawyer, Michael Avenatti, is a sleaze who is now facing a multitude of unrelated federal felony charges. Deborah Ramirez’s allegations were also self-discrediting. She refused to testify, no one at Yale University remembered seeing Kavanaugh expose himself to her, and she claimed to have clarified her recollections by spending six days wracking her alcohol-soaked memories “with an attorney provided by Democrats.”

Blasey Ford’s story was the most credible of the accusations, and her emotional testimony impressed many. But former prosecutor Rachel Mitchell’s gentle questioning revealed how insubstantial Ford’s claims were: no location, no date, no recollection of how she got to the party or got home. Furthermore, the witnesses Ford named as having attended the party, including her longtime friend Leland Keyser, recalled nothing of the sort.

Initially, Keyser had declared that although she could not corroborate her friend’s story, she still believed her. But “Justice on Trial” reveals that after her first interview with the FBI, Keyser had time to reflect and review details of the summer of 1982, and

she lost confidence in Ford’s account of the incident and came to the conclusion that she had to supplement her statement to the FBI…During the second interview, Keyser described the summer with much more detail, adding that she didn’t believe there was any way she was at this gathering. She expressed concern at the pressure she had felt to go along with the story…She detailed certain parts of the story that didn’t make sense to her.

Keyser no longer trusted her old friend’s account, and though she did not want Kavanaugh on the Supreme Court, she would not lie to try to keep him off of it. Without corroboration, and with her inconsistencies exposed, Ford’s tale withered, leaving Democrats with nothing but bizarre theories about the juvenile jokes in Kavanaugh’s high school yearbook (had he perjured himself by wrongly defining “boof”?) and petulant complaints that he had become too upset when they falsely accused him of gang rape.

This was not enough for Sen. Susan Collins, who had not been intimidated by the media frenzy or the harassment campaign directed at her. After a careful examination of the record, she concluded that Kavanaugh was likely innocent and cast the deciding vote to confirm him.

It’s Not Over, By a Long Shot

For the new justice, the worst of his trials were over, but the next nominee may face an even greater ordeal. As Kavanaugh joined the court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg was absent with significant health problems.

There will be more nominations that make the left fear for its ill-gotten judicial gains. “Justice on Trial” reminds us of their ruthlessness in such battles. It also vaccinates against the sort of revisionist history that has occurred since the Thomas confirmation. At the time, public opinion overwhelmingly favored Thomas, but the media never stopped presuming him guilty, and that view has become Democratic dogma.

Democrats will undoubtedly complain that “Justice on Trial” is a biased history, and it does not provide the same insight into the Democratic side as it does for Republicans. But absent new evidence supporting the allegations against Kavanaugh, it does not matter beyond an academic interest in the Democrats’ strategy.

Furthermore, the questions it leaves unanswered are uncomfortable for the Democrats. For instance, who leaked Ford’s letter, and why did Ford prepare for a public fight—high-powered lawyers, social media scrubs, a polygraph, and much more—even though she insisted she had not wanted to go public? Why, after all this preparation, did she and her lawyers repeatedly try to delay her testimony, including the easily disproven claim that she was terrified of flying?

There could have been a confidential, professional investigation early in the confirmation process, but instead Ford’s story was held and then leaked at the last minute. The Democrats chose to make the confirmation process into a public parade of grotesques, and the media gleefully went along, amplifying every ludicrous smear. “Justice on Trial” provides a thorough record of media malfeasance that shows why Trump’s “enemy of the people” insults resonate with so many voters.

Voters Figured Out What Happened

Trump’s selection of outstanding judges, and the depths to which the Democrats stooped to try to stop them, also rallied Republican voters (myself included) for the midterms and beyond, likely boosting GOP gains in the Senate and stemming losses in the House. An outraged Sen. Lindsey Graham spoke for us all when he told his Democratic colleagues off: “Boy, y’all want power. God, I hope you never get it.”

We should share this righteous anger. Democrats are so desperate to preserve their illegitimate judicial victories that they are trying to destroy the lives and reputations of good men and women. We must resist such political wickedness.

In addition to opposing the bad, we must cultivate and love the good. We should love our country and our Constitution, a love that will be made manifest, in part, by defending the rule of law, including the rights of the accused, both legally and in our culture.

These virtues are not only for conservatives. In a saga where few on the left come out looking good, Keyser appears as an American hero, unwilling to lie for political gain. Collins, a moderate disliked by many conservatives, reached a decision for Kavanaugh based on the evidence and fundamental American principles of justice.

There is room for genuine and principled disagreement over the meanings of laws and of the Constitution. What is antithetical to our Constitution, and deeply harmful to our nation, is the belief that judicial power is a political weapon to be exploited for maximum advantage. Using the Supreme Court as the “nuclear bomb of political warfare” exchanges the rule of law for despotism in the hope that the latter will be enlightened. It rarely is.

Nathanael Blake is a Senior Contributor at The Federalist. He has a PhD in political theory. He lives in Missouri.