By Mike Vaccaro

https://nypost.com/2019/07/11/jim-bouton-never-let-ball-four-repercussions-ruin-him/

July 11, 2019

This was during the last and most brutal baseball strike, on an August afternoon in the terrible hot summer of 1994. Baseball was on most people’s hit list, which is the reason I’d gotten in my car and driven to a ballpark in Newburgh, N.Y. Jim Bouton was appearing there that night. It seemed the perfect time to talk to him.

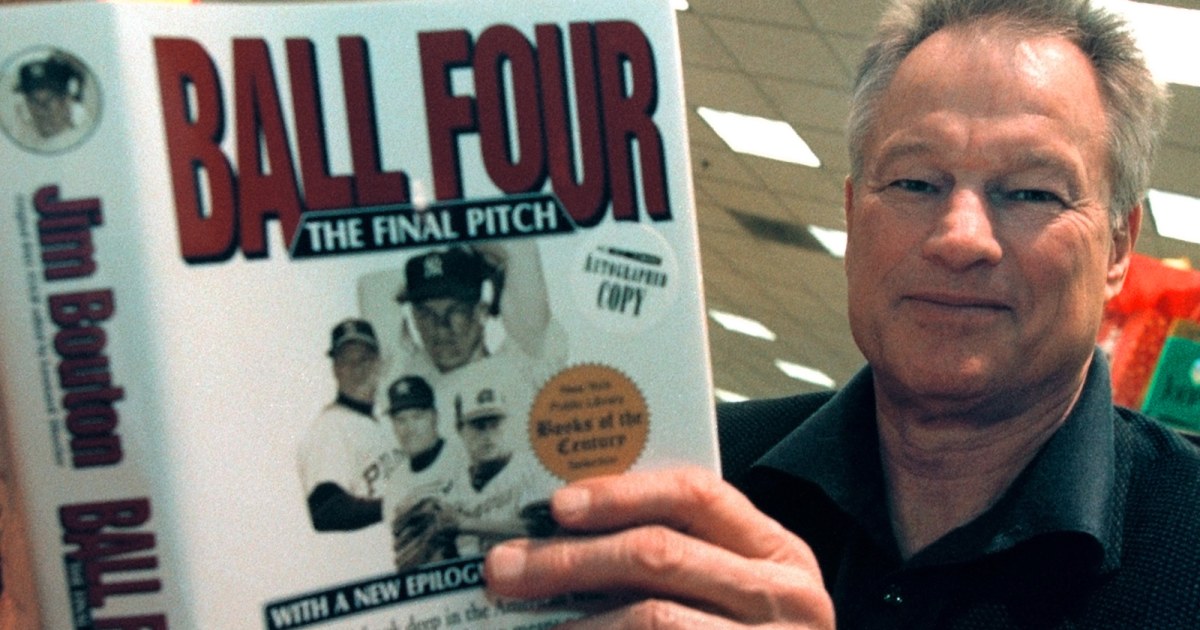

He greeted people before the game, and he was more than happy to sign autographs, mostly of dog-eared copies of “Ball Four.” Time and again, he would draw a laugh by giving a variation of the same line: “I know a lot of people want baseball players to say they’d play for free. But baseball players who play for free all have something in common: They’re not good enough anymore than anyone wants to pay them.”

I got my audience with him late. I told him a story he’d surely heard 100,000 times by then, how reading “Ball Four” had changed the way I’d looked at baseball, how it humanized ballplayers, even God-like ballplayers. How it made me appreciate the game in a whole other way. And how it made me laugh like hell.

He signed my book, “To Mike: If I’m responsible for bringing one more sportswriter into this world, then it’s pretty clear I’m never getting into Heaven. Jim Bouton.”

Bouton died Wednesday at 80 at his home in the Berkshires after a long and difficult decline. The cause of death was vascular dementia, but he’d also suffered a stroke in 2012, and in 2017, he revealed he had a brain disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

He was a mostly middling pitcher, known mainly for a pair of quirks: As a young player, he threw with such a vicious motion that his hat would often fly off when he delivered his fastball. Later, as he struggled to keep a place in the game — the central storyline of “Ball Four;” the hijinks and the laughs were just a bonus — he developed a knuckleball.

As a 24-year-old kid with the Yankees, he’d been good enough to go 21-7 with a 2.53 ERA in 1963, when he made his only All-Star team and finished 16th in the American League MVP voting. He won 18 more in 1964, then added two of the Yankees’ three victories in the World Series against the Cardinals.

Jim Bouton loses his cap while pitching for the New York Yankees in the 1964 World Series. (AP)

By 1965, though, he was 4-15, and his ERA ballooned to nearly 5. He’d already earned a reputation for dancing to his own drummer, whether it was in his yearly salary squabbles with Ralph Houk that he detailed gleefully in “Ball Four,” or for his left-leaning opinions, something that stands out in baseball clubhouses that have always tilted the other way.

Of course, it wasn’t until “Ball Four” that he became a household name. Bouton had always found a kindred spirit in a former Post baseball writer named Leonard Schecter, himself something of an oddity in the press box because he tended to write baseball stories that weren’t always limited to a baseball diamond.

Bouton spent the 1969 baseball season talking into a tape recorder as he tried, and succeeded, to make the expansion Seattle Pilots, as he earned a demotion to Vancouver and then a trade to Houston, introducing the world to a colorful Pilots manager named Joe Schultz and an unknown Seattle rookie named Lou Piniella, traded to Kansas City before the season started. He’d send the tapes back East to Schecter. The writer knew right away they had something; it turned out to be literary gold.

Bouton’s tales of ballplayer byplay and bacchanalia were irresistible to readers. “Ball Four” sold millions of copies and remains in print 49 years later, and was the only sports book included in the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of “Books of the Century.” It also sent the baseball establishment into a tizzy; Commissioner Bowie Kuhn called it “detrimental to baseball” and press box vanguard Dick Young called both Bouton and Schecter (who died in 1974) “social lepers.”

“Bleep you, Shakespeare!” Pete Rose howled at him once, from a dugout.

Bouton shrugged it all off, found fame and fortune as a sportscaster, as an actor, as the first investor in “Big League Chew” baseball gum, as a ballplayer again (he made it back to the bigs in 1978, starting five games for the Braves), as an author of four other books. If there was one consequence that hurt him, it was the Yankees never invited him to Old-Timers’ Day, fearful of how some of the stars of “Ball Four” — notably Mickey Mantle — might react.

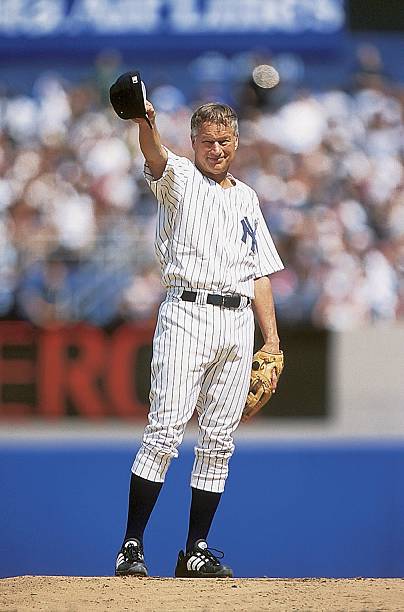

But after Bouton’s daughter, Laurie, was killed at age 31 in a 1997 car accident, his son, Michael, wrote a letter to the New York Times the following Father’s Day, appealing to the Yankees to forgive and forget. The cheers he heard July 25, 1998, were louder than any he’d ever heard as a ballplayer. There were 55,638 people at the Stadium that day; you can bet most were cheering the author every bit as much as the pitcher.

Old-Timer's Day, 1998 (Chuck Solomon/Getty Images)

And you can bet as Bouton let those cheers wash over him, he remembered the last sentence of his book, as good a closing line as you could ever summon.

“You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball,” he wrote, “and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

No comments:

Post a Comment