Editor's note: Larry Alex Taunton is the founder and executive director of the Fixed Point Foundation. This article is adapted from his book “The Grace Effect: How the Power of One Life Can Reverse the Corruption of Unbelief.”

By Larry Alex Taunton, Special to CNN

12/16/2011

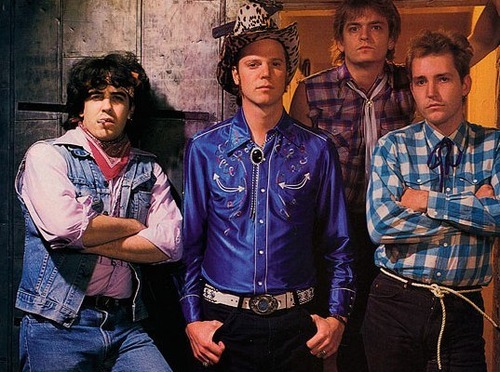

Christopher Hitchens, standing, debates his friend Larry Taunton.

(CNN)– I first met Christopher Hitchens at the Edinburgh International Festival. We were both there for the same event, and foremost in my mind was the sort of man I would meet.

A journalist and polemicist, his reputation as a critic of religion, politics, Britain's royal family, and, well, just about everything else was unparalleled. As an evangelical, I was certain that he would hate me.

When the expected knock came at my hotel room door, I braced for the fire-breather who surely stood on the other side of it. With trepidation, I opened it and he burst forth into my room. Wheeling on me, he began the conversation as if it was the continuance of some earlier encounter:

“The Archbishop of Canterbury has effectively endorsed the adoption of Sharia law. Can you believe that? Whatever happened to a Church of England that believed in something?” He alternated between sips of his Johnnie Walker and steady tugs on a cigarette.

My eyebrows shot up. “‘Believed in something?’ Why, Christopher, you sound nostalgic for a church that actually took the Bible seriously.”

He considered me for a moment and smiled. “Indeed. Perhaps I do.”

There was never a formal introduction. There was no need for one. From that moment, I knew that I liked him. We immediately discovered that we had much in common. We were descendants of martial traditions; we loved literature and history; we enjoyed lively discussion with people who didn’t take opposition to a given opinion personally; and we both found small talk boring.

Over the next few years, we would meet irregularly. The location was invariably expensive, a Ritz Carlton or a Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse. He disliked cheap restaurants and cheap liquor. In his view, plastic menus were indicative of bad food. I never ate so well as when I was with Hitch.

More than bad food, however, he disliked unintelligent conversation. “What do you think about gay marriage?” He didn’t wait for a response. “I don’t get it. I really don’t. It’s like wanting the worst of both worlds.” He drank deeply of his whiskey. “I mean, if I was gay, I would console myself by saying, ‘Well, I’m gay, but at least I don’t have to get married.’” That was classic Hitch. Witty. Provocative. Unpredictable.

Calling him on his cell one day, he sounded like he was flat on his back. Breathing heavily, there was desperation in his voice.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, anticipating some tragedy.

“Only minutes ago, I was diagnosed with esophageal cancer.” He was almost gasping.

I didn’t know what to say. No one ever does in such moments, so we resort to meaningless stock phrases like, “I’m sorry.” Instead, I just groaned. I will never forget his response:

“I had plans for the next decade of my life. I think I should cancel them.”

He asked me to keep the matter private until he could tell his family and make the news public. Hesitatingly, I told him that while I knew that he did not believe in such things, I would pray for him. He seemed genuinely moved by the thought.

“We are still on for our event in Birmingham, right?” He asked. I was stunned. Sensing my surprise, he continued. “I have made a commitment,” he insisted. “Besides, what else am I going to do? I can’t just sit around waiting to die.”

As time approached, he suggested a road trip from his D.C. apartment to my home in Birmingham, Alabama.

“Flying has become a humiliating experience, don’t you think?” He said. “Besides, I haven’t taken a road trip in 20 years and it will give us a chance to talk and for me to finally take you up on your challenge.”

Arriving in Washington some five months after his diagnosis, I was shocked by his appearance. Heavy doses of chemotherapy had left him emaciated, and hairless but for his eyelashes. His clothes hung off of him as though he were a boy wearing a man’s garments. He was, nonetheless, looking forward to our journey, having packed a picnic lunch and, predictably, enough Johnnie Walker for a battalion. After breakfast with his lovely wife, Carol, and his sweet daughter, Antonia, Hitch and I headed south on an eleven-hour road trip.

“Have you a copy of Saint John with you?” He asked with a smile. “If not, you know I do actually have one.” This was a reference to my challenge of two years before: a joint study of the Gospel of John. It was my assertion that he had never really read the Bible, but only cherry-picked it.

“Not necessary.” I was smiling, too. “I brought mine.”

A few hours later we were wending our way through the Shenandoah Valley on a beautiful fall morning. As I drove, Hitch read aloud from the first chapter of John’s Gospel. We then discussed its meaning. No cameras, no microphones, no audience. And that always made for better conversation with Hitch. When he referenced our journey in a televised debate with David Berlinski the next day, various media representatives descended on me to ask about our “argument.” When I said that we didn’t really argue, they lost interest.

But that was the truth. It was a civilized, rational discussion. I did my best to move through the prologue verse by verse, and Christopher asked thoughtful questions. That was it.

A bit put off by how the Berlinski event had played out, Hitch suggested we debate one another. Friend though he was, I knew that Hitch could be a savage debater. More than once I had chaired such engagements where Hitch went after his opponents remorselessly.

Hence, I was more than a bit anxious. Here he was, a celebrated public intellectual, an Oxonian, and bestselling author, and that is to say nothing of that Richard Burton-like, aristocratic, English-accented baritone. That always added a few I.Q. points in the minds of people. With hesitation, I agreed.

We met in Billings, Montana. Hitch had once told me that Montana was the only state he had never been in. I decided to complete his tour of the contiguous United States and arranged for the two of us to meet there. Before the debate, a local television station sent a camera crew over to interview us.

When he was asked what he thought of me, a Christian, and an evangelical at that, Hitch replied: “If everyone in the United States had the same qualities of loyalty and care and concern for others that Larry Taunton had, we'd be living in a much better society than we do.”

I was moved. Stunned, really. As we left, I told him that I really appreciated the gracious remark.

“I meant it and have been waiting for an opportunity to say it.”

Later that night we met one another in rhetorical combat. The hall was full. Christopher, not I, was of course the real attraction. He was at the peak of his fame. His fans had traveled near and far to see him demolish another Christian. Overall, it was a hard-fought but friendly affair. Unknown to the audience were the inside jokes. When I told a little story from our road trip, he loved it.

The debate over, I crossed the stage to shake Christopher’s hand. “You were quite good tonight,” he said with a charming smile as he accepted my proffered hand. “I think they enjoyed us.”

“You were gentle with me,” I said as we turned to walk off the stage.

He shook his head. “Oh, I held nothing back.” He then surveyed the auditorium that still pulsed with energy. “We are still having dinner?” he asked.

“Absolutely.”

After a quick cigarette on the sidewalk near the backstage door, he went back inside to meet his fans and sign their books.

There was something macabre about it all. I had the unsettling feeling that these weren’t people who cared about him in the least. Instead, they seemed like a bunch of groupies who wanted to have a photo taken with a famous but dying man, so that one day they could show it to their buddies and say, “I knew him before he died.” It was a sad spectacle.

Turning away, I entered the foyer, where 30 or so Christians greeted me excitedly. Mostly students, they were encouraged by what had happened onstage that night. Someone had spoken for them, and it had put a bounce in their step. One young man told me that he had been close to abandoning his faith, but that the debate had restored his confidence in the truth of the gospel. Another student said that she saw how she could use some of the same arguments. It is a daunting task, really, debating someone of Hitchens' intellect and experience, but if this cheery gathering of believers thought I had done well, then all of the preparation and expense had been worth it.

The next day, the Fixed Point Foundation staff piled into a Suburban and headed for Yellowstone National Park. Christopher and I followed behind in a rented pick-up truck. Accompanied by Simon & Garfunkel (his choice), we drove through the park at a leisurely pace and enjoyed the grandeur of it all.

The second chapter of John’s Gospel was on the agenda: The wedding at Cana where Jesus turned water into wine. “That is my favorite miracle,” Hitch quipped.

Lunching at a roadside grill, he regaled our staff with stories. Afterwards, he was in high spirits.

“That’s quite a - how shall I put it? A clan? - team that you’ve got there,” he said, watching the teenage members of our group clamber into the big Chevrolet.

“Yes, it is,” I said, starting the truck. “They enjoyed your stories.”

“I enjoy them.” He reclined his seat and we were off again. “Shall we do all of the national parks?”

“Yes, and maybe the whole Bible, too,” I suggested playfully. He gave a laugh.

“Oh, and Larry, I’ve looked at your book.” He added.

“And?”

“Well, all that you say about our conversation is true, but you have one detail wrong.”

“And what is that?” I feared a total rewrite was coming.

“You have me drinking Johnnie Walker Red Label. That’s the cheap stuff. I only drink Black Label.”

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Larry Alex Taunton.