How Dinesh D’Souza Became a Victim of Obama’s Lawless Administration

By Andrew C. McCarthy — December 19, 2015

http://www.nationalreview.com/

Precious were the recriminations after the first Democratic presidential debate. Putative nominee Hillary Clinton, amid what is more a coronation than a contest, had proudly boasted of making the Republicans her “enemy.”

“How despicable,” GOP graybeards gasped. After all, this is just politics, not war. At the end of the day, we’re all fellow patriots, all in this together: not “red states and blue states,” as that notorious bipartisan, Barack Obama, framed it in the 2004 convention speech that put him on the map, but “one people . . . all of us defending the United States of America.”

Dinesh D’Souza begs to differ. He would tell you that Hillary hit the nail on the head, and that we’d better get a grip on that or we will lose the country that we love.

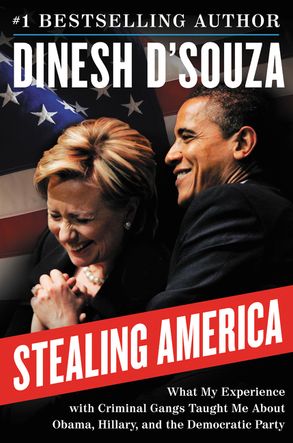

D’Souza has come about this realization the hard way, as he explains in his remarkable new book, Stealing America: What My Experience with Criminal Gangs Taught Me about Obama, Hillary, and the Democratic Party. For his “experience with criminal gangs,” to which he alludes in the book’s subtitle, the prolific conservative author and filmmaker has the president to thank.

The book, part memoir, part polemic, part prescription, and part Kafka, opens with an account — frightening because it is so verifiably true — of one of the grossest abuses of power by this lawless administration: the prosecution of D’Souza for a campaign-finance offense.

The case was not trumped up. D’Souza forthrightly concedes that he violated the law. Wendy Long, his good friend and Dartmouth classmate, was waging a futile campaign against incumbent U.S. senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D., N.Y.). With the press of business leaving him unable to be more of a campaign presence, D’Souza decided to provide financial support. He had, however, already donated the personal maximum of $10,000. So he convinced two friends to be nominal contributors, with D’Souza reimbursing them the combined $20,000.

The offense was foolish. There are simple devices, such as giving to political-action committees, to circumvent the personal-contribution limit. D’Souza’s ignorance of the byzantine campaign laws led him to do illegally what he could easily have done legally. The statute is clear, though: Exceeding the personal limit is a felony carrying a potential of two years’ imprisonment and a hefty fine.

Yet there were patent mitigating circumstances, starting with the fact that few people actually get prosecuted at all for this offense. Even in the case of gargantuan violations, such as the Obama 2008 campaign’s own millions of dollars in illicit contributions, the Justice Department allows cases to be settled with an administrative fine. Furthermore, in the few cases that are pursued criminally, there is unvaryingly a corruption angle — the donor is dodging the limits in the expectation of a quid pro quo.

In D’Souza’s case, there was nothing of the kind: He was trying to be supportive of a friend who had no chance to win (and, in fact, was trounced by 44 percentage points). Add to that the trifling amount involved and the fact that D’Souza had no criminal record (but a record of charitable good works), and it became obvious that this was no federal criminal case.

D’Souza had nevertheless, as Mrs. Clinton might say, made himself an enemy of Obama, a man as vengeful as he is powerful. In the stretch run of the president’s 2012 reelection bid, D’Souza released his documentary film 2016: Obama’s America, which drew heavily on his bestselling 2010 book, The Roots of Obama’s Rage, a chronicle of Obama’s upbringing in the radical Left. The film was extraordinarily successful and drew sharp rebukes from the White House and Obama allies.

It is no coincidence, D’Souza convincingly argues, that the Obama Justice Department scorched the earth to convict and attempt to imprison him. The brazenness of its aggression took the breath away from such hardened criminal-defense attorneys as Harvard’s Alan Dershowitz, an Obama supporter who found the vindictiveness of D’Souza’s prosecution shameful, and Benjamin Brafman, the legendary New York City defense lawyer who represented D’Souza.

Among the highlights of the book is the transformation of Brafman, another political progressive, who started out believing that D’Souza was paranoid to think that the president of the United States even cared about his case, much less had it in for him, but ended up convinced that D’Souza had been railroaded. The conclusion is inescapable: His client was indicted in a matter routinely disposed of with a fine; to get bail, D’Souza had to post a bond of $500,000 (i.e., $125,000 more than the mere fine the Justice Department allowed the Obama 2008 campaign to pay in settlement of violations geometrically larger than D’Souza’s); to pressure D’Souza to plead guilty, prosecutors gratuitously charged a second felony count — a “false statements” offense that should not have been added since a campaign-finance violation necessarily involves a false statement; after D’Souza did plead guilty — rather than risk seven years’ imprisonment — Justice pressed the court to impose a 16-month jail sentence despite the de minimis nature of the crime; and, in so pressing, prosecutors blatantly misrepresented the applicable sentencing law.

The last straw for Brafman was the start of the sentencing hearing, when Judge Richard Berman subjected D’Souza to a bizarre tongue-lashing. Clearly, the jurist appointed by President Bill Clinton was poised to accede to prosecutors’ demand for a prison term. The outraged lawyer responded with a tour de force, placing the case and D’Souza’s basic decency in context. It worked: Berman was dissuaded from imposing a prison term.

But what he did to appease Justice’s baying for blood was arguably worse. Berman sentenced D’Souza to eight months of halfway-house confinement, a form of detention that requires the defendant to spend the nighttime hours in a spartan, dormitory-type facility but to work in the local community during the day.

In D’Souza’s circumstances, the sentence was irrational except as a form of abuse. A halfway house is designed to be transitional confinement: a way for a convict who has usually served years in prison to spend the last few months of his sentence gradually reentering the community while otherwise continuing to be monitored. No such transition is called for when, as in D’Souza’s case, the defendant was never incarcerated in the first place.

Moreover, had D’Souza been given the 10-to-16-month sentence prosecutors urged, he’d have been sent to a minimum-security prison camp with other low-level offenders. A halfway house, by contrast, is a way station for serious criminals: murderers, rapists, gang-bangers, big-time drug traffickers, and the like.

These would be D’Souza’s housemates and confidants for the eight months prior to his release last May. To be sure, it is not the same as encountering such hardened criminals in prison. In a halfway house, the imminence of release and the possibility of being sent back to prison for misconduct are a powerful incentive to good behavior. Still, for a man as foreign to this element as D’Souza was, the prospects were cause for great anxiety — which was not relieved when, upon arriving at the facility in a rundown part of San Diego, he found that the first order of business was a mandatory class on how to avoid being sexually assaulted. In a flash of bureaucratic idiocy, a leitmotif of the book, D’Souza was informed that, if he were to be raped, he would be entitled to a free pregnancy test.

D’Souza, it turns out, was relieved to find that his companions comported themselves with civility. Characteristically, he used the trying experience as an opportunity to learn and grow.

The principal evolution in the author’s thinking involves seeing his political adversaries as, yes, enemies. And as criminals. As a conservative intellectual, D’Souza had assessed progressives as true believers in an utterly flawed ideology. He was a forceful advocate of the conservative counter-case: liberty, limited government, human fallibility, the wisdom undergirding our traditions. Yet implicit in his arguments was the sense of engagement in a real battle of ideas against a bona fide political opponent.

After his harrowing adventure — first, in the crosshairs of a corrupt executive branch that knows that the administration of governmental processes can ruin even the most innocent of men, never mind one who has actually committed an infraction; then, in the company of lifetime criminals whose lives are mainly about taking what is not rightfully theirs — D’Souza has changed.

Progressives, he now perceives, are engaged in a massive scheme to “steal America,” meaning all of its wealth and traditions. Their ideas and the foibles of their interest-group politics are often incoherent because they are not actually meant to cohere. They are, instead, a Machiavellian ploy, a pretense to morality (because the public expects it) that camouflages the remorseless acquisition of power needed to rob the public blind.

The author’s new insight has a significant corollary. D’Souza, like most conservatives, used to be dismissive of progressive narratives about social justice that portray common folk as victims of American history’s “oppressive legacy,” preyed upon by capitalist titans and administrators of the criminal-justice system. Now, he has become convinced that the system is, in fact, unfair — not for the reasons cited by progressives but precisely because of progressive influence on the system.

Their grip on power — crony capitalism, discretion over prosecutorial decisions, the promotion of favored factions — robs Americans of economic opportunity and subjects them to abuses of governmental process.

D’Souza’s time spent with criminals has revealed for him a symmetry between the operations of gangs and those of progressives, particularly in proceeding through the stages of theft from plan, through recruitment and rationalization, and finally on to cover-up. The means by which gang-bangers and social-justice crusaders extort and justify their ill-gotten gains are, of course, different, but D’Souza sees no appreciable difference in their basic schemes.

At times, this analogy is overstated and Stealing America’s effort at thematic connection between criminal heists and political corruption can seem strained. D’Souza’s nightmare has persuaded him that the sociopaths with whom he interacted compare favorably with corrupt government officials when it comes to owning up to their flawed character and fraudulent practices. But while rogue politicians and “activists” deserve no defense, I would simply observe — having spent almost 20 years as a prosecutor — that criminals are frequently more introspective and forthright when they are in captivity. It has more to do with their circumstances than with any wisdom they have acquired.

Still, this does not detract from D’Souza’s overarching thesis. America flourished because it was an anti-theft society: freedom inextricably linked to the protection of private property, unleashing creativity, entrepreneurship, and unprecedented prosperity. The progressive critique of that society is not advanced in good faith; it is, as D’Souza portrays it, a “con.” Its purpose — not its unintended consequence but its aim — is to seize the wealth and power of achievers. The con is systematized by the Democratic party now under Obama’s leadership, with Hillary waiting in the wings.

Dinesh D’Souza implores us to recognize the con for what it is, and work, as he works, to expose it, rather than dignify it as an alternative political philosophy. America, he contends, is well on the way to being stolen. We will lose our country if we fail to reaffirm our anti-theft roots.

— Andrew C. McCarthy is a policy fellow at the National Review Institute. His latest book is Faithless Execution: Building the Political Case for Obama’s Impeachment. This article originally appeared in the December 21, 2015, issue of National Review.

* National Review magazine content is typically available only to paid subscribers. Due to the immediacy of this article, it has been made available to you for free. To enjoy the full complement of exceptional National Review magazine content, sign up for a subscription today. A special discounted rate is available for you here.