September 16, 2017

First-time success: Jane Harper's The Dry has exceeded all expectations. Photo: Pat Scala

When Jane Harper decided to become a novelist, she recognised there was a hitch in the plan. Quite a big one. "I wasn't sure how to write a novel," she says, as afternoon light streams into her bayside Melbourne apartment. "I didn't know how you started it, or how you pulled all the pieces together to get to the end."

Harper is a practical person. If her ambition had been to tile her bathroom floor, she would have enrolled in a floor-tiling course. As it was, she signed up for a novel-writing course, which sure enough, gave her the guidance she needed. Gradually she got the hang of turning out chapters and in 12 weeks she produced a 40,000-word draft of a murder-mystery set in a drought-stricken Victorian town. "I didn't have any real expectation that this book would be published," she says. "I thought, 'I'm just going to try to finish it and I'm going to learn what I can from it. And then maybe I can write a better book next time'."

Harper, who is 37, with pale skin and auburn curls, permits herself a smile. Her murder-mystery did make it into print. The Dry is something of a publishing phenomenon — a bestseller that has won rave reviews and a swag of prizes in this country, including being named book of the year at the 2017 Australian Book Industry Awards. Now it's climbing the international charts. In The New York Times, the respected critic Janet Maslin called it "a breathless page-turner" and expressed amazement that it was the work of a novice. In the UK, the major book retailer Waterstones took the unusual step of selecting it as thriller of the month for both June and July. British GQ magazine has tipped it to be "the biggest crime release of 2017". At last count, it has been translated into 24 languages, most recently Macedonian. A movie deal has been signed.

For Harper, whose second book is due out late this month, all this is a little overwhelming. At the time I visit her, she is just back from speaking at crime-writing festivals in England and Sweden, and is preparing to head to the US for an author's tour. Who knew being a novelist involved so much travel? "My whole life has changed beyond recognition," she says as we drink tea in her living room.

She is chuffed, obviously, but determined to keep a level head. As she sees it, her success is proof that there is nothing magical about creating compelling fiction: all you really need do is make the effort to pick up the tricks of the trade, then roll up your sleeves and get on with the job. "Writing is a skill that can be taught and learnt," she says. "I think it's like any skill, really — like dancing or painting or swimming or anything like that. Some people are naturally good at things but most people can benefit from professional instruction."

In the publishing world, where it's taken for granted that authors have oversized egos and seething neuroses, Harper is regarded as a delightful oddity. Amiable. Matter of fact. Low maintenance. "She's a no-fuss personality," says Cate Paterson, publishing director at Pan Macmillan Australia and editor of The Dry. "Jane is just so fresh. So natural. Dare I say, normal, in a good way."

Paterson pauses, possibly thinking about The Dry's shocking opening scene. "Which is not to say she breezes over the darkness in life."

When I read the book last year, I presumed that Harper herself must be an escapee from some dusty corner of the hinterland, so vividly does she conjure up the shimmering heat, the peeling paint, the crackle of dry eucalyptus leaves, the isolation. In fact she was born on the other side of the world, in the well-watered English city of Manchester. At the age of eight, she migrated with her family to Melbourne, but six years later they returned to Britain. Her parents eventually settled in north Yorkshire, where her mother taught English to Gurkhas based at a nearby military barracks, and her father, who had spent most of his career in the computer industry, opened a guitar shop.

Harper trained as a journalist and by 28 was ensconced at the Hull Daily Mail in east Yorkshire, enjoying the work but ready for a change of scenery. "I think I always expected I would come back at some stage," she says of her decision to move on her own to Australia. "I sent off my CV to a whole lot of newspapers and got offered a job on the Geelong Advertiser." She arrived in the Victorian port city in 2008, at the tail-end of one of south-eastern Australia's worst droughts on record. People talked about its terrible impact but for Harper the message didn't really hit home until she took a picnic to a spot in the bush that her family had often visited during her childhood. Here, fire had followed drought. "The trees looked quite dead and the creek was gone," she says. "I remember being so shocked. It had gone from being this green, lush place to what looked like a barren wasteland."

She moved to Melbourne in 2011, after landing a job as a finance writer on the Herald Sun. Three years later, when she was 34, she decided it was time to realise a long-held aspiration. "I'd always had this underlying feeling that I would love to write a book," she says. So she applied to join an online novel-writing course offered by an offshoot of the London branch of literary agency Curtis Brown. "You had to send off a synopsis of a book you wanted to work on, and a 3000-word opening. I sat down and thought, 'What would I like to write about?'"

As the course progressed, the 15 participants submitted pieces of their work for appraisal by their fellow students. "All that group discussion I found quite useful," says Harper, who at first adopted a more flowery prose style than she used as a journalist. "I thought, 'It's fiction. I must put in all these adjectives'. But people said, 'There's a lot of unnecessary description here'. And as soon as they said that – "You don't need it' – I was like, 'Oh great! I can cut it out then.' Because I didn't really enjoy writing it."

The course ran for the last three months of 2014, and Harper set herself the target of completing her first draft by the end of the year. Right on schedule, on December 31, she composed the last sentence, which gave her a quiet sense of achievement even if she had a hunch that her work had only just begun. "It was quite bare," she says of the story. "The plot was essentially there but not much else. The characters were probably pretty two-dimensional. I basically went straight back to the beginning and started rewriting it."

Since Harper was a full-time finance journalist, spending her days covering the ins and outs of the retail industry, she worked on the novel in the evenings and at weekends. Her instinct was to play down the project. Apart from her partner, journalist Peter Strachan, the only people who knew about it were her parents and two siblings. The family joke was that the manuscript's working title was My Stupid Book. "I obviously didn't write that at the top of the page or anything," Harper says. "It was more like, 'I'm going to do a couple of hours on my stupid book'."

With each successive draft, she gave the characters more depth and strengthened the plot, adding twists and turns, inserting red herrings here and there. There was nothing tortured about the process. Writing requires concentration, of course, but for Harper it is no more angst-ridden than, say, laying tiles. "I don't agonise," she says. "I approach it logically and just take it step by step."

It wasn't as if she was trying to write the great Australian novel: her goal was merely to come up with an example of the kind of fast-paced, well-constructed mystery story that she enjoyed reading herself. Entering the unpublished-manuscript category of the 2015 Victorian Premier's Literary Awards was a way of extending the learning exercise. "I'll send off the best version I have and maybe get some more feedback," she remembers thinking.

When Harper won the $15,000 prize, Victoria MacDonald realised with a start what her friend had been doing with her spare time since she stopped sewing classes. "We were all fairly gobsmacked, everyone who knew her," says MacDonald. But no one was more incredulous than Harper herself. "Of all the things that have happened, that was possibly my favourite moment," she says. "It was the moment when I thought, 'There is actually a possibility that this book will get published.' Suddenly I had emails pinging every 20 minutes. Agents and publishers saying, 'Can we read it?' Which is your dream scenario, really."

She signed with agent Clare Forster, of Curtis Brown Australia, who combed through the manuscript, making notes and offering suggestions. "Jane went away and came back with the most dazzling rewrite," says Forster, who was struck by the acuity of Harper's vision of her adopted homeland. "She has such a distinctive and powerful grasp of the Australian landscape and psyche."

Harper has picked up the lingo, too. Her own accent is English, but on paper she perfectly captures Australian patterns of speech – a knack she attributes at least partly to the fact that newspaper reporting involves so much interviewing. "You're constantly listening to what people say, transcribing it verbatim and then turning it back into legible copy. I think that really helped get my ear in."

Strachan and Harper married in August 2015, on the same day Pan Macmillan won the auction of her Australian publishing rights. "It was the happiest day of my life," says Harper, who had probably known Strachan was the man for her from the moment he agreed to accompany her to Latin dancing classes.

The couple started with the salsa, she tells me, then moved on to the rhumba, the cha-cha, the pasodoble and the jive. "It went from a really casual thing to actually taking private lessons and then taking exams." Harper laughs. "Suddenly you've got special shoes and everything." Neither she nor Strachan was born to set the dance-floor alight, she says. But with much the same sense of resolve she brought to learning novel-writing, "we turned up to classes every week and we listened to what our teacher said and tried to take that on board. You keep on doing that and gradually you do improve, don't you?"

A few weeks after the wedding and the Australian auction, US and UK publishers paid six-figure sums for the right to publish Harper's first three books in those markets. She was just getting over that excitement when she got the news that the movie rights to The Dry had been optioned. "The line was really bad," remembers Harper, who had to ask Forster to tell her again who had bought them. "She said, 'Reese Witherspoon, the actress'. I said, 'Yeah, I know who Reese Witherspoon is.' That was unbelievable. Completely out of the blue."

By the time the book was released in Australia in June last year, a lot of people had a stake in its success. For Harper, promoting The Dry had become an almost a full-time job in itself, and she had decided with some trepidation to resign from the newspaper. "Quitting the day job is quite a big step," she points out. "Plus I really loved the people I was working with." But she knew she soon would have had to take extended leave anyway – she was pregnant with her daughter, Charlotte, now almost a year old. Also, she was itching to get stuck into her second novel.

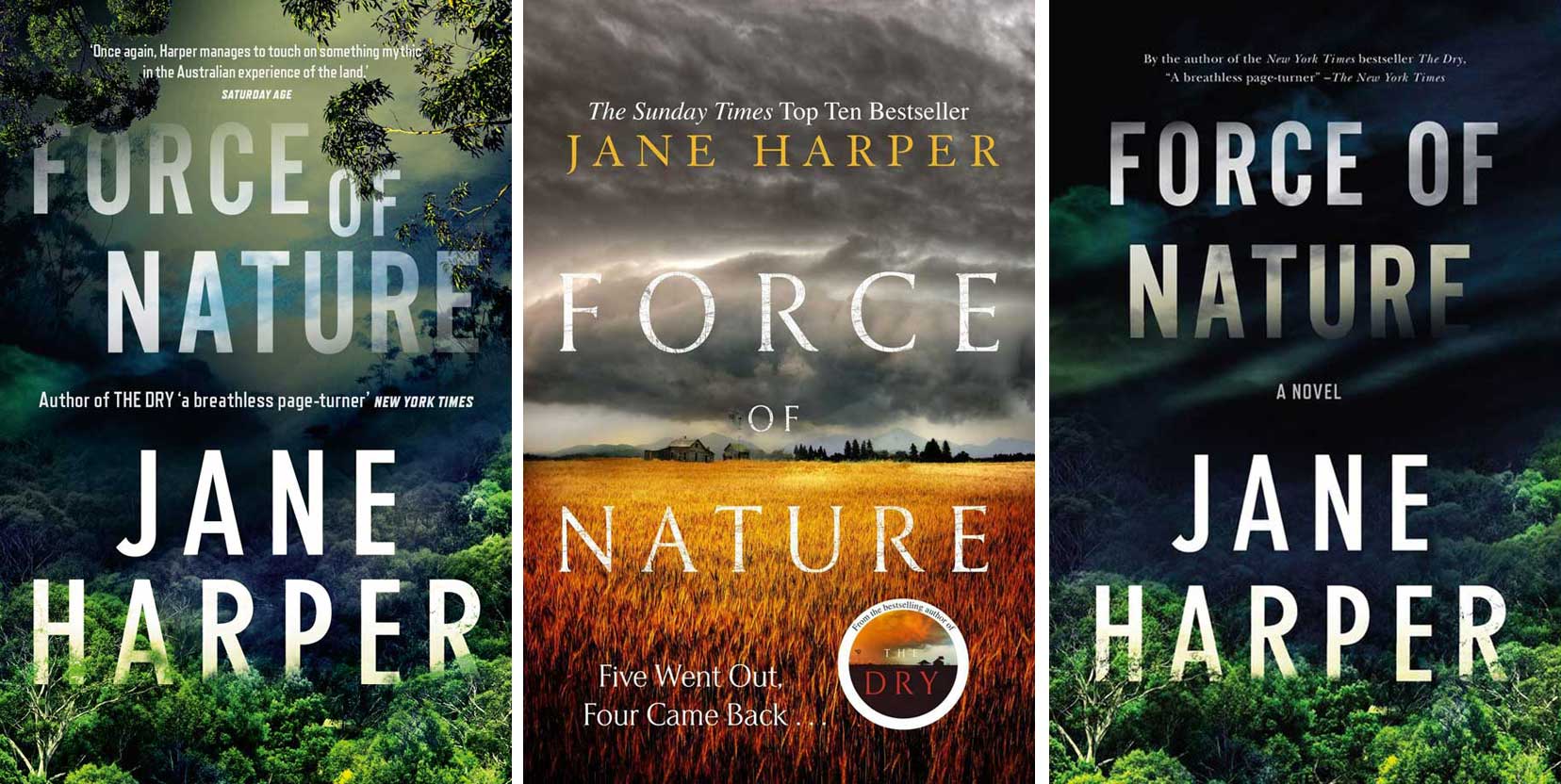

Force of Nature is a sequel to The Dry in as much that the investigator is again laconic Aaron Falk, an officer in the Australian Federal Police financial intelligence unit. As in the first book, the setting is everything, but this time the action takes place in the fictional Giralang Ranges, a rugged, heavily forested region east of Melbourne. Five women, reluctant participants in a corporate team-building exercise, pick up their backpacks and walk into the bush. A few days later, only four of them come out.

In this story, there is a dash of Lord of the Flies – "group dynamics under pressure", as Harper puts it – as well as an echo of Agatha Christie's country-house murder-mysteries. "It's quite good, plot-wise, to have an isolated setting, in the sense of keeping the cast of characters fairly contained," Harper says. Just as Christie's readers knew when the house-guests gathered in the drawing room for the denouement that one of them must have bumped off the Colonel, we have little doubt that one of the four survivors of the Giralang trek is responsible for the death of the fifth woman.

They say the second book is always the hardest. But it seems to Cate Paterson that the challenge for Harper must have been particularly daunting because of the runaway success of her first. Like a person who wins the jackpot the first time she puts a coin in a poker machine, she could easily have been left with the slightly guilty feeling that she should have served a longer apprenticeship. While Harper juggled the demands of her newfound literary celebrity with the even more urgent demands of a new baby, she had to try to write a novel that measured up to The Dry. "I thought, 'How is she going to have the concentration?'" says Paterson.

There were some stressful moments, Harper admits. Becoming a mother was "such a huge upheaval really, emotionally and practically and time-wise". Strachan cared for Charlotte a lot – at least when he wasn't at the office – but to people who ask how she got Force of Nature written, Harper says she honestly doesn't know. "When I look back, it is a bit of a blur."

According to Bruna Papandrea, the Australian producer with whom Reese Witherspoon bought the film rights to The Dry, the script of the movie is close to completion and shooting is expected to begin next year. Papandrea has a sure touch: her production credits with Witherspoon include the Oscar-nominated films Gone Girl and Wild, and the recent hit series Big Little Lies, based on the novel by best-selling Australian author Liane Moriarty. She says she found Harper's book unputdownable: "I read it overnight, as I do when I love something."

An Australian, Robert Connolly, has been engaged to direct the movie, which Papandrea plans to make in Victoria. But she sees this as a story with universal appeal. "My idea is to make it a phenomenal international thriller," she says.

Meanwhile, the book has been short-listed for the coveted Gold Dagger, awarded by the Crime Writers' Association of the UK to the best crime novel of the year. "Wow, Jane, go!" says Harper's course tutor, Lisa O'Donnell, who dismisses her portrayal of herself as the literary equivalent of a paint-by-numbers artist. "I can always tell a good writer," O'Donnell says. "They're full of empathy and they're full of generosity. And Jane is just one of those people. You can feel when someone has it, and Jane was definitely one of those students."

Nonetheless, O'Donnell wouldn't necessarily have picked Harper as the member of the tutor group who would find fame and fortune. "I thought her book was exceptional," O'Donnell says. "But there were other books, one in particular, that I felt the same way about. And nothing happened with that book. The truth is, this business is so very arbitrary. The stars were aligned for Jane."

Michael Harper, two years Jane's junior, is inclined to agree with his sister's self-assessment. "It sounds almost cruel but I wouldn't say she was naturally gifted," says Michael, an international tax consultant, who moved to Australia soon after Harper. He argues that what she has by the bucketload is application. Whether writing a novel, playing the violin or doing the rhumba, she acquits herself well because "she's conscientious, she's hard-working, she pays attention to the fundamentals".

Michael is particularly pleased that Harper's willingness to have a go has brought her financial rewards. "She's taken a chance and it's paid off," he says. "It's wonderful. I did her tax returns for her when she was a journalist and I remember thinking it wasn't a huge wage by any standards. I think she would feel ten times as secure as she was."

Harper assures me she managed perfectly well in the past, partly because she has always been sensible with money. It was because she was tired of paying someone to take up her jeans that she started sewing classes, for instance. Still, she knows what her brother means. "It's been an incredible couple of years," she says. "I've been really lucky."