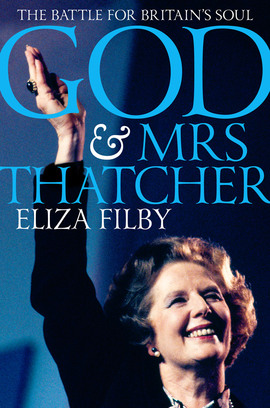

By Eliza Filby — October 31, 2015

"Economics is the method; the object is to change the soul.” So said Margaret Thatcher. The Iron Lady always believed that democratic capitalism involved the transformation of values as much as it did the improvement of Britain’s ailing GDP. Yet few people are aware that Thatcher was a woman of profound faith. She had been a lay Methodist preacher while a student at Oxford University. Later, she would transfer this missionary energy from the pulpit to the political podium.

The solid Christian base for Margaret Thatcher’s politics goes back to her strict Methodist upbringing and, more specifically, to her father — greengrocer, councilor, and Wesleyan lay-preacher, Alf Roberts. As a child, Margaret Roberts would sit in the pews of Finkin Street Methodist Church in Grantham, listening to her father hammer home sermons on the individualized nature of faith, God-given free will, moral and fiscal restraint, and the Protestant work ethic. If one were sourcing the origins of Thatcher’s free-market ideology, one should not look to the pages of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom or Milton Friedman’s monetarist theory, but in the sermons of her father. In short, Thatcherism — a belief in freedom, individual free will, and social responsibility — always owed more to Methodism than to monetarism.

Luckily for historians, Thatcher kept her father’s sermons, which are now housed in her personal archive at Cambridge University. In keeping with the Methodist tradition, the notes reveal an emphasis on the individual call to faith (“The Kingdom of God is within you!”) and the Protestant work ethic (“a lazy man” was one who had “lost his soul already”). Alf Roberts believed that just as “God refuses to put grace on a tariff,” so should there not be any tariffs imposed on the free market. This was a doctrinal legitimation of the “invisible hand,” which his daughter would enunciate with equal passion 40 years later. In Roberts’s view, the real danger in the modern world was not poverty but affluence. “No man’s soul can be satisfied with a materialistic philosophy,” he warned, but only with “the stern discipline and satisfaction of a spiritual life.” The struggle of how to morally square the free market with the materialist culture it created was something Thatcher would wrestle with throughout her premiership.

In the mid 1970s, Thatcher found that the principles of the New Right chimed with the lessons she had heard her father preach from the pulpit. The economic arguments for a smaller state suited her Methodist inclination towards thrift; a stress on individual liberty complemented her Non-conformist grounding in God-given free will; while the idea that employment should be a matter of individual responsibility rather than the state’s mirrored her belief in the Protestant work ethic.

As one of her chief aides Alfred Sherman correctly noted, Margaret Thatcher “was a woman of beliefs, not ideas.” In this, Sherman above all recognized that Christian values and convictions were central to Mrs. Thatcher’s DNA.

Assured of the Christian underpinning of her political philosophy, Thatcher therefore considered it her duty to challenge the perceived association (then being promoted in many Christian churches) between liberal politics and Christian principles. “It was to individuals that the Ten Commandments were addressed,” Margaret Thatcher would retort. She believed that as Christianity called men individually, it followed that political choices should reside with the citizen rather than the state. “The Good Samaritan could only have helped because he had money” was Margaret Thatcher’s response to the idea that redistributive taxation could generate compassion and virtue. For Thatcher, Christian fellowship could only be practiced at an individual level.

Thatcher’s faith also profoundly shaped her outlook on the great cause of the age: the Cold War. Alongside Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II, Thatcher played a crucial role in the propaganda offensive against the Eastern Bloc, asserting the moral superiority of Christian Western values against those of atheistic Communism.

During his days as governor of California, Ronald Reagan had mastered the language of conservative Evangelicals and their message of revival and salvation from the pernicious forces of hedonism — which stood him in good stead as president. Regarding his personal faith, Reagan was known to pray regularly, but was not an active churchgoer. It also appears he did not object to his wife’s insistence that they consult an astrologer over his actions and appointments. It was his mother, though — the other great female figure in his life – who had inspired his Christian faith. Nelle Reagan was a committed member of the Disciples of Christ Church in Illinois and would conduct church readings, run Bible study classes, and (it was said) even perform healings. The Bible-based tutelage that Reagan received at the Disciples of Christ Church in Illinois was not a world away from the teaching Margaret Thatcher received at Finkin Street Methodist Church in Grantham.

Speaking in London in 1975, not long before his first bid for the White House, Reagan set out the choice facing the world: “Either we continue the concept that man is a unique being capable of determining his own destiny with dignity and God-given inalienable rights . . . or we admit we are faceless ciphers in a godless collectivist ant heap.” His critics may have dismissed his understanding as simplistic while admirers praised his assured principles. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that Reagan’s worldview was shaped by and articulated in Christian terms.

Margaret Thatcher too was willing to elevate the Cold War into one of values from the moment she became leader of the Conservative party in 1975. “I’m perfectly prepared to fight that battle,” Thatcher enthused to her foreign-policy adviser George Urban. “We’ve got all the truth on our side and all the right arguments.” In 1983, soon after her triumph in the Falklands, Thatcher asserted in her acceptance speech for the Winston Churchill Foundation Award in Washington, D.C., that the Cold War was one chiefly of ideas not weapons:

“If we do not keep alive the flame of freedom that flame will go out, and every noble ideal will die with it. It is not by force of weapons but by force of ideas that we seek to spread liberty to the world’s oppressed.”

For Thatcher, the fight against socialism at home and Communism abroad was a fight for liberty and individual free will. From her earliest childhood, she had always understood these tenets to be central to the Christian faith. Indeed, Thatcher’s father never doubted that totalitarianism amounted to the suppression of God-given free will, which, he said, “can end in the systematic dehumanization of man.” Thatcher gave a similar homily on liberty when in 1989 she delivered an address just as the Communist experiment was being reduced to rubble: “Remove man’s freedom and you dwarf the individual, you devalue his conscience, and you demoralize him.”

It was that moral fervor, rooted in her Christian faith and her father’s principles, which was the source of iron will in the Iron Lady.

— Eliza Filby is a lecturer in contemporary values at King’s College, London. This piece is adapted from her new book, God and Mrs. Thatcher: The Battle for Britain’s Soul. Follow her on Twitter @ElizaFilby.