The last of the brave thinkers and authors in this tradition are long gone. Can anyone replace them?

By

October 5, 2018

Though the term is rarely employed in our time, “Christian humanism” is one of the noblest movements of the last century. It’s a concept much older than the 20th century, of course, dating back to St. Paul’s visit to Mars Hill in Athens. There, Paul had challenged the Greek Stoics to discover and embrace their “unknown god.” A few decades later, St. John the Beloved sanctified the 600-year-old Heraclitean concept, logos (meaning fire, imagination, word), at the beginning of his Christian gospel.

Russell Kirk

Following this ancient tradition, many of the greatest of Western thinkers—from St.Augustine to Petrarch to Sir Thomas More to Edmund Burke—had inherited and breathed new life into Christian humanism during their own respective ages. In the 20th century, two men—T.E. Hulme in the United Kingdom and Irving Babbitt in the United States—reclaimed the 1,900-year-old concept, believing it the only possible serious challenge to modernity, the exaggeration of the particular, and the rise of ideologies and other inhumane terrors. From the grand efforts of Hulme and Babbitt a whole cast of fascinating characters arose, embracing Christian humanism to one degree or another: T.S. Eliot, Paul Elmer More, Frank Sheed and Maisie Ward, Willa Cather, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, J.R.R. Tolkien, Nicholas Berdyaev, Etienne Gilson, Jacques Maritain, Theodor Haecker, Aurel Kolnai, Bernard Wall, Sigrid Undset, Thomas Merton, Flannery O’Connor, and Russell Kirk.

After the latter’s immense success with the 1953 publication of The Conservative Mind, the young author worried that conservatism could serve only as a critique of the previous age, not as blueprint for a way forward. Conservatism, after all, was the “negation of ideology,” challenging more than answering. If one considered himself a conservative, Kirk believed, he must prudently understand what needs conserving. To this, Kirk argued, only human dignity and a well-ordered society—rooted in eternal virtues and principles—were worth preserving. Such vital things, he determined in 1954, could only happen with a revival of “Christian humanism” and not merely through conservatism. Christian humanism alone was timeless, while conservatism was a momentary response to the immediate past. Though Kirk returned once again to “conservatism” as the central focus of his writings in the late 1950s, his books, essays, lectures, and periodicals (Modern Age and The University Bookman) never strayed far from his own understanding of Christian humanism.

It must also be noted that “Christian humanism” could almost as easily and appropriately—at least by its advocates and allies in the 20th-century—be called “Judeo-Christian humanism.” It’s primary American founder, Irving Babbitt, for example, certainly did not believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ, and he wanted thinkers such as Aristotle, Cicero, and the Buddha to have equal standing with the Nazarene. Other essential Christian humanist allies, such as Eric Voegelin, held heterodox views, believing, for example, that St. Paul was a Gnostic and a Manichean, too quick to dismiss the physical side of life. Still others, such as Leo Strauss, were somewhat Jewish and utterly Zionist. A proper Christian humanism could, most of its advocates believed, not only incorporate any who believed in the dignity of the human person, but also transcend whatever differences existed in the name of dignity.

♦♦♦

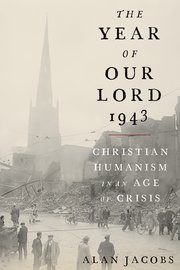

Admittedly, I was absolutely thrilled when I first learned that Baylor University scholar Alan Jacobs would be writing on the subject—and taking it seriously. Indeed, Jacobs is not only serious about Christian humanism, he repeatedly identifies himself personally with the idea. The book becomes so personal at times—with language employed such as “I suspect” and “I think”—that the reader has the feeling he is sitting in an intimate seminar room with Jacobs as the scholar meditatively pontificates on works he has lovingly read and absorbed over years of careful scholarship. As it is, then, The Year of Our Lord 1943 is as much about Jacobs’s own ideas as it is about 1943. Jacobs even writes parts of the book in the present tense, making it even more personal and immediate.

Relying almost entirely on primary source material but filtered through the rather personal thought, intellect, and soul of the present author, Jacobs considers the fears and desires of five major but seemingly disparate figures in 1943 as they envision a post-war world after an Allied victory: W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, Jacques Maritain, and Simone Weil. These are not the only figures who make an appearance, though they are the central five in Jacobs’s study.

Tellingly, perhaps, each of Jacobs’s five was a writer of significance, though their modes differed dramatically, from prose and philosophy to plays and poetry. They were also not uniform in their faith. Maritain is the only Catholic, while Auden, Eliot, and Lewis were faithful members of the Church of England, and Weil, though raised in a secular Jewish family, embraced what might be called a liturgical form of evangelical Christianity. Nor did they all get along. Lewis, famously, despised Maritain and Eliot, though he and Eliot reconciled in the late 1950s while revising the Book of Common Prayer.

Others who appear in the book include Christopher Dawson, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, J.R.R. Tolkien, Mortimer Adler, Reinhold Niebuhr, Hannah Arendt, Karl Barth, Henri De Lubac, Robert Maynard Hutchins, Thomas Merton, J.H. Oldham, and even Roger Waters (of Pink Floyd). The main five, therefore, are all English (Eliot being an American expatriate and Auden being the reverse Eliot) or continental European, though many of Jacobs’s supporting characters are American.

From the beginning of the book, Jacobs admits that one might readily regard his choice of these five—Maritain, Weil, Lewis, Auden, and Eliot—as unusual ones. They often disagreed with each other, as noted above, and sometimes they did not even like each other. Yet they each believed that the Western civilization of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had paved the way for the ideologies of National Socialism and communism to arise. Each, after all, had developed not only under the shelter of Western civilization, but around westerners working to undermine Western civilization itself. Simultaneously, no one in the West was providing a counter to these ideologies, but rather other forces were moving civilization toward despair, nihilism, and meaninglessness; the Western tradition seemed impotent to answer the threats posed by national and international socialism.

♦♦♦

It was certainly healthy to be anti-Nazi and anti-communist for the vast majority of westerners, but what exactly did a good member of Western civilization believe? That is, what positive thing motivated him to defend the work of his ancestors? Would Americans of the 1930s still rally to the cry of Leonidas or even Davy Crockett? Decades of liberal progressivism, pragmatism, and positivism had neutered the citizens of the West, rendering them incapable of clear and objective thought.

As legendary University of Chicago president and Great Books editor Robert Maynard Hutchins so poignantly asked in 1940, as the country was on the brink of war, “What Shall We Defend?” Hutchins never doubted science or scientific progress. What he doubted was the capability of mid-20th century citizens of Western civilization to engage in moral reasoning. Only in the ability to seek and find truth in the moral sphere, Hutchins argued, could true human flourishing occur. Thus Jacobs muses after his summation of Hutchins, “only a clearly articulated and rationally defended account of true justice can resist totalitarianism.”

In one of the best chapters of The Year of Our Lord 1943, “The Humanist Inheritance,” Jacobs writes penetratingly about the concept and lineage of Christian humanism. Though “humanist” was coined, originally, as a term of 16th century student slang, it was a course of liberal academic study that placed its greatest hopes in literature rather than philosophy, and “on the wisdom to be gained from pagan classical writers and thinkers.”

Echoing much of the work done by Christopher Dawson as well as that, more recently, by James Hitchcock, Jacobs clearly analyzes the tension between the more literary and Augustinian humanism and the more rational and Thomistic humanism, noting that each has much to offer and each is equally Christian, whatever its particular adherents might have claimed. Rather than beginning his story of modern humanism with Babbitt’s and Hulme’s works of the 1890s and 1900s, however, Jacobs starts with the profoundly influential 1920 work, Art and Scholasticism, by Jacques Maritain. As Jacobs sees it, Maritain properly called for “not a rejection of humanism but a reclamation of it.” In this sense, it would follow closely in the line of the humanism of St. Paul’s day, not by destroying the pagan inheritance of the liberal arts, but by sanctifying it.

While each of the other four central figures of 1943 might ignore or despise Maritain, Art and Scholasticism began a series of questions that would dominate the efforts and ideas not only of Maritain himself, but also those of Eliot, Weil, Lewis, and Auden. As World War II demonstrated a crisis of humanity, so only a “restoration of the specifically Christian understanding of the human being” could solve it, Jacobs notes. Additionally, “this restoration will not be accomplished only, or even primarily through theology as such, but also and more effectively through philosophy, literature, and the arts.”

Though Jacobs does not make the following claim explicit in his book, one might readily add “politics” to the list of things that will not restore the world to sanity and order.

♦♦♦

The second-best chapter in 1943 is “Demons,” in which—at least somewhat surprisingly to this reviewer—Jacobs makes a convincing case that the five major figures of his book feared demonic influence and intrusion into the world of the 20th century as not just symbolic, but possibly as quite real. With such an assertion, one immediately is reminded of the story of Pope Leo XIII’s 1884 vision of demons wandering and ravaging the face of the earth. Whether tangible or corporeal or not, the concept of the “demonic” certainly offers the perfect descriptive for the end of a humanism not rooted in the good, true, and beautiful—whether Platonic, Stoic, Mosaic, or Christian.

At times, some of Jacobs’s views are simply shocking, if not somewhat scandalous. Without any hesitation or qualification, Jacobs calls T.S. Eliot’s 1939 book, The Idea of a Christian Society, “a masterpiece of vagueness and evasion.” Or again, on Eliot’s famous lecture to the Virgil Society, “What is a Classic?,” in which the Anglo-American poet elaborated on works of Virgil—The Aeneid, The Eclogues, and The Georgics—as the touchstone of all post-Roman literature. Jacobs believes that it is “Eliot’s prose at its worst; and that means that it is very bad prose indeed.” One can only imagine what the generally unrufflable Russell Kirk—or the equally gentle souls of Flannery O’Connor or Thomas Merton—might write in response to such pronouncements.

Jacobs’s very short conclusion—simply the final paragraph of the book—makes it clear that he believes the last moment for Christian humanism in the West existed just prior to and just after 1943. Courageously, Maritain, Eliot, Lewis, Auden, and Weil “put forth every effort to redeem the time,” Jacobs writes in Pauline fashion. “If ever again there arises a body of thinkers eager to renew Christian humanism, they should take great pains to learn from those we have studied here.”

It is unfortunate that Jacobs leaves his fine—if not extraordinary book—on such a dour note. For a counterpoint, one might turn to Pope John Paul II, who called for an open and full revival of Christian humanism in a late 1996 address:

The mystery of the Incarnation has given a tremendous impetus to man’s thought and artistic genius. Precisely by reflecting on the union of the two natures, human and divine, in the person of the Incarnate Word, Christian thinkers have come to explain the concept of person as the unique and unrepeatable center of freedom and responsibility, whose inalienable dignity must be recognized. This concept of the person has proved to be the cornerstone of any genuinely human civilization.

A massive number of websites and works of scholarship have since emerged on Christian humanism, all taking inspiration from John Paul II. Though Jacobs does not state it explicitly, perhaps he is attempting to renew the same call, 22 years later.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.

No comments:

Post a Comment