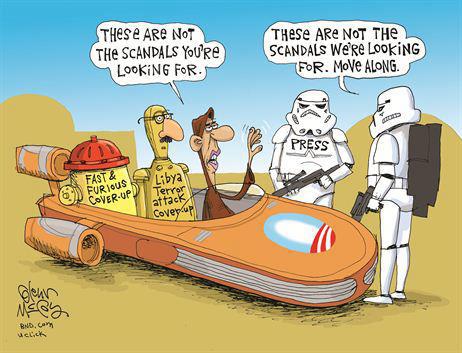

The media just pretended they didn't exist.

From the January 16, 2017 issue

Less than a fortnight after his successor was elected, Barack Obama got to work on shaping his legacy. “I'm extremely proud of the fact that over eight years we have not had the kinds of scandals that have plagued other administrations," he said. On January 1, White House consigliere Valerie Jarrett—does anyone have a firm grasp on what her actual job description has been over two terms?—appeared on CNN and reiterated the sentiment: "The president prides himself on the fact that his administration hasn't had a scandal and that he hasn't done something to embarrass himself."

As achievements go, this would be one in which a modern president could take pride. But in making the claim for himself, Obama proves he cannot even accurately describe the events of his presidency. His tenure saw an astounding number of scandals: Benghazi, Fast and Furious gunrunning, Solyndra and green energy subsidies for campaign donors, cash for Iranian hostages, IRS targeting of conservative groups, spying on journalists, Hillary Clinton's private email server, the Veterans Administration disaster, trading deserter Bowe Bergdahl for five Taliban leaders held in Guantánamo, droning American citizens without due process, and firing inspector general Gerald Walpin for investigating an Obama crony who was abusing federal programs. And that list isn't exhaustive.

The media have certainly tried their best to buttress Obama's claim to have presided over a scandal-free administration—starting long before he even made it. In 2014, New Yorker editor and Obama biographer David Remnick told the (skeptical) host of PBS's Charlie Rose that the president had already racked up "huge" achievements. On his list: "The fact that there's been no scandal, major scandal, in this administration, which is a rare thing in an administration." Remnick was hardly alone. Veteran journalist Jonathan Alter wrote a column for Bloomberg back in 2011 headlined "The Obama Miracle, a White House Free of Scandal." More recently, Glenn Thrush, then a Politico reporter, tweeted, "As Obama talks up legacy on campaign trail important to note he's had best/least scandal-scarred 2nd term since FDR." Even conservative New York Times columnist David Brooks last year declared the Obama administration "remarkably scandal-free."

Remnick's remark is particularly notable for how it presaged White House talking points. Obama's chief campaign strategist David Axelrod was asked at the University of Chicago in 2015 about the administration's broken promise to bar lobbyists from working for it. Axelrod admitted things hadn't been "pristine" but said, "I'm proud of the fact that, basically, you've had an administration that's been in place for six years in which there hasn't been a major scandal."

As Noah Rothman observed in Commentary, "The qualifier 'major' lays the burden on shoulders of the press to define what constitutes a serious scandal, and political media had thus far reliably covered the administration's ethical lapses as merely the peculiar obsessions of addlebrained conservatives."

So what would constitute a "major" scandal? Would it involve, say, dead bodies? The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives gave thousands of guns to Mexican drug cartels; they used some of them to kill dozens of people, including American border patrol agent Brian Terry. When Congress tried to investigate why the ATF gave away so many guns and failed to track them, the Department of Justice engaged in unprecedented stonewalling. The department withheld 92 percent of the documents requested and forbade 48 relevant employees from speaking to congressional investigators. Attorney General Eric Holder was ultimately held in contempt of Congress, with 17 Democrats supporting the measure. An explanation for why the ATF gave thousands of guns to violent criminals has yet to emerge—but we are to understand that this is not a "major" scandal.

Four Americans, including the ambassador to Libya, died in a premeditated terrorist attack in Benghazi two months before Obama's reelection. The White House claimed, though it almost immediately had evidence to the contrary, that the raid was fallout from a spontaneous protest over an American anti-Muslim YouTube video. The maker of the video was promptly arrested on old, unrelated charges. The CBS news program 60 Minutes recorded Obama refusing to rule out the possibility Benghazi was a terrorist attack in an interview the day after it occurred but didn't broadcast it. A transcript of Obama's stunning concession was quietly released a few days before the election, but by then the waters had been sufficiently muddied so that it was difficult for Mitt Romney to press his case that Obama had lied. (The GOP candidate was famously interrupted by moderator Candy Crowley when he tried to make this point in one of the presidential debates.) It probably helped that Obama's deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes, who would later brag about dishonestly selling the Iran nuclear deal, is the brother of CBS News president David Rhodes. There were four dead bodies at the heart of a political cover-up, but the media attacked the subsequent investigation as an overreach of an obsessive Republican Congress.

Unforeseen events such as Benghazi often prompt a cover-up that leads to scandal. The Obama administration, however, took disrepute to the next level. Its two major achievements, Obamacare and the Iran nuclear deal, were premised on a strategy that embraced overt dishonesty.

It's liberating to know that you can tell whatever lies are politically useful without consequence. The Obama administration could almost always count on the media to back it, regardless of the contortions necessary. The most brazen untruth the administration used to sell Obamacare was "if you like your health care plan, you can keep it." Pulitzer Prize-winning "fact checker" PolitiFact rated Obama's oft-repeated claim "true" six different times, right up until the year after Obama was reelected and millions lost their health insurance after the key provisions of Obamacare went into effect.

In the case of the Iran deal, the administration had more direct help: An outside group, the Ploughshares Fund, provided a grant for an email listserv in which liberal journalists honed talking points and directed swarms of supporters to shut down anyone advancing arguments critical of the deal. Ploughshares also gave more than a hundred thousand dollars to left-leaning media outlets such as NPR to ensure arguments in support of the White House's Iran policy were heard.

"We created an echo chamber," Ben Rhodes later told the New York Times in explaining how the administration sealed the Iran deal. Policy experts and members of the media "were saying things that validated what we had given them to say."

The question is: Why was the press such a willing partner? Several Obama scandals, after all, revolved around the administration's mistreatment of the media. Obama's Justice Department, frustrated by leaks to reporters, used the 1917 Espionage Act—a law so expansive it was used to jail people who distributed flyers protesting the draft in World War I—to justify spying on the Associated Press newsroom and Fox News national security correspondent James Rosen. James Goodale, the lawyer who represented the New York Times in the landmark Pentagon Papers press freedom case, declared that "President Obama will surely pass President Richard Nixon as the worst president ever on issues of national security and press freedom." The steadfastly fawning coverage of Obama is even more difficult to fathom when you realize the masochism it must have entailed.

In the end, the real legacy of the Obama presidency might be that after eight years of constant misconduct with media-assisted denial, abuse of power and betrayal of the public trust are no longer scandalous by default. The media certainly seem puzzled that Americans tuned out their shrieks about Trump's tax returns and sexist remarks. But thanks to Obama, determining what constitutes a scandal is no longer straightforward. It is like a zen koan, in which the question is more evocative than answerable: What is the sound of one hand clapping? If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? And is it a scandal if the media refuse to say it is?

Mark Hemingway is a senior writer at The Weekly Standard.

No comments:

Post a Comment