By Mike Bird

October 13, 2016

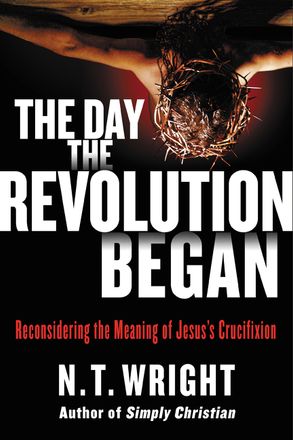

A foundational Christian belief is that Jesus Christ died on the Cross for our sins. For many, the most important result of this is that believers go to heaven when they die. Bestselling author, scholar and bishop, N. T. Wright, thinks we’re missing a critical aspect of what Jesus accomplished on the Cross if we limit our understanding just to this explanation. His latest book, The Day the Revolution Began, explores the Crucifixion and argues that the Protestant Reformation did not go far enough in tranforming our understanding of this event. Mike Bird, author of What Christians Ought To Believe, interviewed Wright about how Christians should view the Crucifixion.

Tom, you describe Jesus' death as the beginning of a "revolution." What was that revolution and why does it still matter today?

Most Western Christians have been taught that Jesus died so that they could escape the results of sin and go to heaven after they die. The New Testament, however, regularly speaks of Jesus’ death as the defeat of the powers of evil that have kept the world in captivity, with the implication that the world is actually going to change as a result—through the life and work and witness of those who believe this good news. Think of Revelation 5:9–10. Humans are rescued from their sin so that they can be “a kingdom and priests serving our God, and they will reign on earth.” That began at Easter and, in the power of the Spirit, has continued ever since. Of course, the “reign” of Jesus’ people, like that of Jesus himself, is the reign of suffering love . . . but that’s a whole other story. Suffice it to say that the vocation of God’s people today is to continue to implement that revolution.

Even as Western cultures grow more secular, we still find the Crucifixion presented in art and echoed in music. Plus the notion of sacrifice for others is still very much a Christian theme that novels like Harry Potter seem to borrow from. Why do you think the cross, its image and message, is so captivating?

It seems as though the world knows in its bones that the cross of Jesus was the ultimate revelation of true power and true love. Most people for some of their lives, and some people for most of their lives, nurse sorrows and wounds whether secret or open; and the thought or sight of Jesus on the cross, perhaps particularly when it’s painted beautifully or set to wonderful and appropriate music, speaks of the true God not as a distant, faceless bureaucrat, nor as a bullying boss, but as the one who has strangely come into the middle of the pains and sorrows of the world and taken their full force on himself. In a sense, all of Christian theology, certainly theology of the cross, is the attempt to explain, to give a wise and scriptural account of, that very immediate, personal, visceral impact.

We tend to think of the cross as a very churchy or religious symbol, like the Apple logo or the McDonald’s sign, but what did the Crucifixion mean for people in the first century?

Crucifixions were common in the first century. It was a fairly standard punishment for slaves or for rebel subjects. It was a way for the Roman Empire to say “We are in power, and this is what we do to people who get in our way.” Crucifixion was unspeakably horrible, with victims often left on crosses for several days, pecked at by birds and gnawed at by vermin. It was deliberately a very public execution, to warn others: When the Spartacus rebellion was put down, roughly 100 years before Jesus’ day, 6,000 of his followers were crucified all along the Appian Way between Rome and Capua, making it more or less one cross every 40 yards for 130 miles. Anybody, and especially any slave, walking anywhere on that road would get the point. But it wasn’t just (what we would call) a “political” point. In Jesus’ day Rome was “deifying” its emperors, at least after their deaths, making the present emperor “son of god.” Rebelling against Caesar’s empire was therefore a kind of blasphemy, and crucifixion a restatement of the theological “fact” that Caesar was “Lord.” That is the context for Mark’s statement that the centurion (a Roman army commander) at the foot of the cross looked at Jesus and said, “Truly, this man was the Son of God.’”

Click on the link below to read the full article:

No comments:

Post a Comment