By ROSS DOUTHAT

http://www.nytimes.com

August 3, 2013

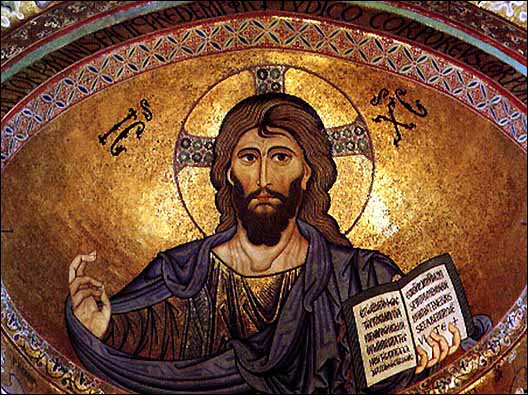

Christ Pantocrator (1148 AD), mosaic, dome of Cathedral of Cefalu, Palermo, Italy.

BEFORE “The Da Vinci Code” and “The Gospel of Judas,” before Mel Gibson’s “Passion” and Martin Scorsese’s “Last Temptation,” before the Dead Sea Scrolls were unearthed and the Gnostic gospels rediscovered, there was a German scholar named Hermann Samuel Reimarus.

It was Reimarus, writing in the 18th century, who basically invented the modern Jesus wars, by postulating a gulf between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith. The real Jesus of Nazareth, he argued, was a political revolutionary who died disappointed, and whose disciples invented a resurrection — and with it, a religion — to make sense of his failure.

In Reimarus’s lifetime these were dangerous ideas, and his argument was published posthumously. But within a few generations, historical-Jesus controversies inspired publicity rather than persecution. By the Victorian era, when the Earl of Shaftesbury attacked David Friedrich Strauss’s “Life of Jesus, Critically Examined” as “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell,” he was just contributing to the book’s success.

Today there are enough competing “real Jesuses” that it’s hard for a would-be Strauss to find his Shaftesbury. Which is why every reinterpreter of Jesus not named Dan Brown is probably envious of Reza Aslan, the Iranian-born academic and author of “Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth,” who achieved Strauss-style liftoff thanks to 10 painful minutes on Fox News.

Those minutes were spent with the interviewer, Lauren Green, asking Aslan to explain why a Muslim would write a book about Jesus — with Aslan coolly emphasizing his credentials and the non-Islamic nature of his argument — and then with Green asking variations on the Muslim question, to increasing offense and diminishing returns.

The video quickly went viral, turning Aslan into a culture-war icon, a martyr to Fox’s biases ... and soon enough (as these things tend to go) a martyr with a No. 1 best seller.

The irony is that Aslan’s succès de scandale would be more deserved if he had actually written in defense of the Islamic view of Jesus. That would have been something provocative and — to Western readers — relatively new.

Instead, Aslan’s book offers a more engaging version of the argument Reimarus made 250 years ago. His Jesus is an essentially political figure, a revolutionary killed because he challenged Roman rule, who was then mysticized by his disciples and divinized by Paul of Tarsus.

The fact that Aslan’s take on Jesus is not original doesn’t mean it’s necessarily wrong. But it has the same problem that bedevils most of his competitors in the “real Jesus” industry. In the quest to make Jesus more comprehensible, it makes Christianity’s origins more mysterious.

Part of the lure of the New Testament is the complexity of its central character — the mix of gentleness and zeal, strident moralism and extraordinary compassion, the down-to-earth and the supernatural.

Most “real Jesus” efforts, though, assume that these complexities are accretions, to be whittled away to reach the historical core. Thus instead of a Jesus who contains multitudes, we get Jesus the nationalist or Jesus the apocalyptic prophet or Jesus the sage or Jesus the philosopher and so on down the list.

There’s enough gospel material to make any of these portraits credible. But they also tend to be rather, well, boring, and to raise the question of how a pedestrian figure — one zealot among many, one mystic in a Mediterranean full of them — inspired a global faith.

That’s not a question such books are usually designed to answer. They’re better seen as laments for paths not taken, Christianities that might have been. The mystical Jesus is for readers who wish we had the parables without the creeds, the philosophical Jesus for readers who wish Christianity had developed like the Ethical Culture movement. And a political Jesus like Aslan’s is for readers who feel, as one of his reviewers put it, that “Jesus’ usefulness as a challenge to power was lost the moment Christians first believed he rose from the dead.”

This means that the best companion reading for “Zealot” probably isn’t an alternative portrayal of Jesus’s life and times. Rather, it’s a recent book like the classicist Sarah Ruden’s “Paul Among the People” or the theologian David Bentley Hart’s “Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies.”

Coming from different vantage points — Ruden is more theologically liberal, Hart more conservative — both authors explore just how radical the actual Christian revolution was, how it upended the ancient world’s violent, patriarchal, hierarchical norms, and how many liberal, modern and egalitarian attitudes are indebted to early Christian zeal.

Theirs aren’t arguments on behalf of a particular vision of who Jesus really was. They’re briefs against the assumption that some other interpretation of his life would have necessarily had more dramatic, congenial or significant results.

And they’re reminders that every modern account of how an alternative Christianitymight have changed the world is itself indebted to the many ways the historical Christianity actually did.

No comments:

Post a Comment