NBA Insider

June 8, 2013

MIAMI -- Julius Erving enjoys the game and what it has become, and he relishes the global success that's on display during the NBA Finals. More than anything, though, he loves to hear the players speak, because sometimes he can hear a little bit of his own voice.

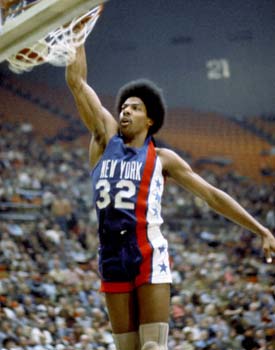

His fingerprints, his giant hand rocking the baby on his way to another gravity-defying dunk in our mind's eye, are all over the game. As we behold LeBron James in his latest championship quest, a straight line can be drawn to the past -- from James to Michael Jordan, and before him, to Dr. J.

None of what the NBA has become would have been possible, would've looked quite like it does, if not for the soaring talents, soothing voice and incomparable style of The Doctor. And so the timing couldn't be better for a remarkable documentary by that name, the story of Erving's life and impact airing Monday night on NBA TV.

"All the basketball stuff, revisiting all that again wasn't burdensome," the great Erving told CBSSports.com. "But it was a challenge to remember and recall a lot of it because it's not something I'm constantly reminded of. You only see so many highlights.

"When you play 1,200 games or more, you're not going to remember all the games -- nor do you want to, nor do you want to be stuck in that place between 1971 and 1987," Erving said. "I don't want to be stuck there. I don't mind going back to visit, but I don't want to run around wearing No. 6 and No. 32."

But this is Erving's time to reflect, and it's our good fortune to reflect with him -- to feel the connection between what the NBA has become and what Erving built. In The Doctor, NBA TV struck all the right notes in dissolving the present into the past in the rich tale of Erving's journey from playground legend to underground star to mainstream sports icon and, finally, flawed human.

And as we absorb all that comes with an epic Finals matchup between the Heat and the Spurs, with the sport reaching what could be its cultural and competitive apex, it's worth remembering the path that was traveled to get here.

"LeBron is such a gifted athlete, and he's way beyond the man-child aspect, the first impression," Erving said. "It's Herschel Walker, Bo Jackson and LeBron, OK? I mean these are guys when they were freshmen in high school, they probably could've been pros. I can only think of those three, and then George McGinnis was probably like that. Some get to the mountaintop and others don't. There's no guarantee.

"Even though you're gifted with that type of body and you're a man-child, you still have to work at it -- work harder than anyone else, still have to develop your skills, still have to increase your IQ in terms of your sport. He's doing all that. ... He's on such a path right now that he could surpass Michael and he could surpass Kareem. Those are the guys I think are the NBA's best of all time. He's in that conversation, and he'll stay in that conversation."

For the modern NBA star, the conversation began with Erving. In The Doctor, Erving's journey from Roosevelt, Long Island, to the University of Massachusetts to Rucker Park -- where the nickname Dr. J was born -- to the ABA and, finally, to the long struggle for an NBA championship with the 76ers, is a timely reminder of what Erving built with his own gifts and wisdom. It has grown and endured beyond his reach -- beyond the shadow of his iconic Afro and his outstretched hand palming the ball.

"I think the game is in a good place," Erving said.

Erving lost his 16-year-old brother, Marvin, to Lupus when he was 19. Tragedy struck again when Erving's 19-year-old son, Cory, disappeared and was later found dead after accidentally driving into a lake near the family's Florida home in 2000.

"Everybody who I've lost still travels with me everywhere I go," Erving said.

Speaking with CBSSports.com recently during the Eastern Conference finals, 13 years to the day after the last time he saw his son alive, Erving said it was important to finally open up about the tragedies of his life.

"That's where my humility comes from, the fact that I've always felt powerless in terms of winning the ultimate test -- the ultimate test, life or death," Erving said. "I feel powerless, and so games didn't have the same meaning for me that they had for so many other people. I could walk away from a game and if I'd done my best; it's acceptable. ... My mission has always been a higher mission."

The documentary only briefly touches on Erving's marital trouble -- he and his wife of 29 years, Turquoise, were divorced in 2003 -- and his two children born out of wedlock. One, pro tennis player Alexandra Stevenson, came to Erving three years ago to make peace with him, Erving told CBSSports.com.

"She came to me in 2010 and I was in Atlanta and she had reached out," Erving said. "She came and she had some things that she wanted to talk about and some issues and some needs. And so we addressed all of the above."

Erving, who has since remarried, described his relationship with Stevenson as "off and on."

"She's 32 years old, she's grown and I have grown children," Erving said. "And I would have to say I don't try to delve into their business. I take what I get from them and I give what I have to give. My doors are always open and I have an open-door policy with my family -- my four sons and three daughters and my four grandchildren. My doors are always open, but I'm not going to chase any of them."

There are no regrets for Erving, 63, only memories and the power of optimism that his best days are still ahead of him. As for what the game has done with the gifts Erving bestowed on it, he has only one serious complaint: statistical achievements in the ABA have not been integrated into the NBA record book, and neither have benefits and other status symbols for so many players who didn't make the cut when the leagues merged in 1976.

"The NBA elected to take the best of the ABA, which was me, George Gervin, David Thompson, Artis Gilmore and the coaches and the 3-point shot and the three referees and certain of the rules," Erving said. "They took the best and just kind of discarded the rest. I know it becomes a statistical nightmare to integrate everything, but fair is fair."

If ABA and NBA statistics were merged, Erving would be among six players who've scored 30,000 career points, joining Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Karl Malone, Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant and Wilt Chamberlain. The NBA record book stops at Chamberlain.

"I think that's a little unfair," Erving said. "There are guys who played professional basketball for five years, seven years, eight years, and it's like they never existed. So I feel more for them."

But Erving also appreciates that so many of the modern stars -- Bryant, James, Kevin Durant -- recognize and speak freely about the path that Erving and others paved for them.

"I don't think LeBron is generous with praise of others," Erving said. "Certainly, those first five or six years he wasn't, and now he is in the later years. That's all part of his growth and development where he could appreciate what transpired before.

"I'm certainly appreciative of anything he has to say that compliments me or other people who have made great contributions to the game of basketball," he said. "And that is a significant part of his evolution."

An evolution that never would have happened quite the way it has without The Doctor.

No comments:

Post a Comment