By Bradley J. Birzer

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/08/jrr-tolkien-beren-and-luthien-bradley-birzer.html

August 2, 2019

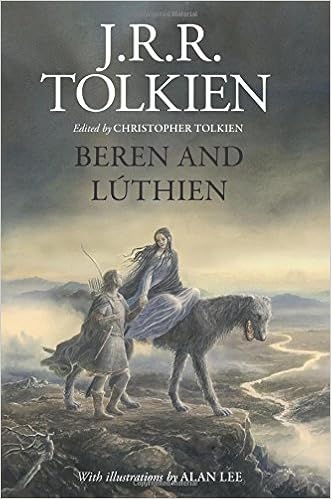

"The chief of the stories of The Silmarillion, and the one most fully treated is the Story of Beren and Lúthien the Elfmaiden,” Tolkien wrote Milton Waldman of Collins Publishers in 1951.[1] Along with The Children of Húrin and The Fall of Gondolin, Beren and Lúthien formed the three greatest tales of the First Age, each, in some way, deeply tied to the saga of the three silmarils. Tolkien wrote them in 1916 and 1917, beginning with The Children of Húrin, following it with the Fall of Gondolin, and completing the main three with Beren and Lúthien.[2] Of the three, Tolkien explained, Beren and Lúthien most foreshadowed The Lord of the Rings. “Here we meet, among other things, the first example of the motive (to become dominant in Hobbits) that the great policies of world history, ‘the wheels of the world,’ are often turned not by the Lords and Governors, even gods, but by the seemingly unknown and weak—owing to the secret life in creation, and the part unknowable to all wisdom but One, that resides in the intrusions of the Children of God into the Drama.”[3] Equally important for Tolkien’s entire mythology, Beren and Lúthien tells the tale of the first marriage of Elf (immortal) and man (mortal), so critical to the entire story.[4]

As with all of Tolkien’s great tales of the First Age, the story of Beren and Lúthien transformed dramatically over sixty years from its first imagining and version in 1916 and 1917 to its relatively finalized version in 1977’s The Silmarillion. During those six decades, it appeared as a long tale of the Lost Tales, as a summary in the 1926 Sketch of the Mythology (written for Tolkien’s beloved professor from King Edward’s, R.W. Reynolds), as a radically ambitious poetic lay, The Lay of Leithian (1925-1931), and as an essential story within the various versions, including the final version, of The Silmarillion.

Yet, the essence of the story has remained the same in all of its many versions. Or, as Christopher so wisely put it, “The fluidity should not be exaggerated: there were nonetheless great, essential, permanences.”[5]

A daughter of an Elf king, Thingol, and a fay (a Maia—the offspring of the angelic powers; roughly of the same power as Gandalf), Lúthien-Tinúviel expressed her joy and love through dance. One day, Beren, a heroic but displaced outlaw, spies her dancing. “Yet now did he see Tinúviel dancing in the twilight, and Tinúviel was in a silver-pearly dress, and her bare white feet were twinkling among the hemlock-stems.”[6] In Tolkien’s Lay of Leithian, he describes in terms comparable only to the Blessed Virgin Mary:

Her starry jewels twinkled bright

In the risen sun like morning dew;

The lilies gold on mantle blue

Gleamed and glistened.[7]

In the risen sun like morning dew;

The lilies gold on mantle blue

Gleamed and glistened.[7]

Enraptured, Beren followed Lúthien to her hidden kingdom, only to be mocked by her father. When Beren expressed his love for Lúthien, her father challenged him to steal one of the three silmarils, lodged and protected in Morgoth’s (the devil; also named Melko and Melkor) iron crown. Accepting the challenge, Beren heads north to Morgoth’s realm and fortress, Angband. Evil dwells throughout the North, Beren quickly finds. “Many poisonous snakes were in those places and wolves roamed about, and more fearsome still were the wandering bands of the goblins and Orcs—foul broodlings of Melko who fared abroad doing his evil work, snaring and capturing beasts, and Men, and Elves, and dragging them to their lord,” Tolkien wrote.[8] Beren becomes a captive in Morgoth’s house, a thrall and house slave. Distraught by her father’s cruel taunts, Lúthien follows Beren north to Morgoth’s realm. En route, she befriends the greatest of dogs, a dog of the angelic powers, Huan. Huan has been given permission to speak to Beren and Lúthien only three times, and, in each, he offers sagacious thought and advice. He also serves as a guardian, even challenging Morgoth’s greatest lieutenant, Sauron, to a fight.

From shape to shape, from wolf to worm,

From monster to his own demon form,

Thû [Sauron] changes, but that desperate grip

He cannot shake, nor form it slip.

No wizardry, nor spell, nor dart,

No fang, nor venom, nor devil’s art

Could harm that hound that hart and boar

Had hunted once in Valinor.[9]

From monster to his own demon form,

Thû [Sauron] changes, but that desperate grip

He cannot shake, nor form it slip.

No wizardry, nor spell, nor dart,

No fang, nor venom, nor devil’s art

Could harm that hound that hart and boar

Had hunted once in Valinor.[9]

Together, though, Huan and Lúthien formulate a plan, and Lúthien comes before Morgoth. In lust, he watches her dance, but her dance entrances him, putting him and his household to sleep. “Even the Orcs laugh in secret when they remember it,” the tale reveals, “telling how Morgoth fell from his chair and his iron crown rolled upon the floor.”[10] Beren and Lúthien remove one of the silmarils from Morgoth’s crown and escape, only to encounter the fell wolf, Carcharoth, who bites off Beren’s hand, consuming it and the silmaril it held. Unable to bear the goodness of the silmaril, Carcharoth goes mad, running wild into the wilderness. Having seen the folly of his words, Thingol joins Beren in the hunt for Carcharoth. They succeed in killing the wolf and removing the silmaril, but only at the cost of Beren’s life. Lúthien pleads with the god of death, Mandos, for Beren’s life.

The song of Lúthien before Mandos was the song most fair that ever in words was woven, and the song most sorrowful that ever the world shall hear. Unchanged, imperishable, it is sung still in Valinor beyond the hearing of the world, and listening the Valar are grieved. For Lúthien wove two themes of words, of the sorrow of the Eldar and the grief of Men, of the Two Kindreds that were made by Ilúvatar to dwell in Arda, the Kingdom of Earth amid the innumerable stars.[11]

Mandos, moved by the beauty of the story, agrees, but he demands, in return, that Lúthien give up her immortality as a fay-Elf. She gladly accepts Mandos’s offer, and she and Beren spend his second life in great joy and adventure.

The story of Beren and Lúthien matters profoundly in The Lord of the Rings. Not only are Aragorn and Arwen (who chooses mortality to be with Aragorn) the intellectual and spiritual descendants of Beren and Lúthien, but Arwen is, actually, a genetic and familial descendent of Beren and Lúthien. And, just as Beren lost his hand in rescuing the silmaril from Morgoth, so Frodo loses a finger in securing the fate of the ring from Sauron. Equally important, though, Aragorn chants the story of Beren and Lúthien, only moments before the Ringwraiths attack at Weathertop. The story serves as a form of prayer, preparing the Hobbits for their first real and tangible battle with evil. It remains one of the most beautiful parts of Tolkien’s entire mythology.

The story also mattered profoundly in Tolkien’s own life. His own wife, Edith, inspired the scene of Lúthien dancing, she having danced for him in “a small wood with a great undergrowth of ‘hemlock’ (no doubt many other related plants were also there) near Roos in Holderness, where I was for a while on the Humber Garrison,” during the First World War.[12] Then, Tolkien told his son, Christopher, Edith’s “hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing—and dance.”[13]

Edith Tolkien’s grave reads “Lúthien,” and J.R.R. Tolkien’s reads “Beren.”

[1] JRRT to Milton Waldman, 1951, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter No. 131.

[2] JRRT to Christopher Bretherton, July 16, 1964, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 257.

[3] JRRT to Milton Waldman, 1951, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 131.

[4] See also, JRRT to Peter Hastings, September 1954, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 153.

[5] Christopher Tolkien, “Preface,” to J.R.R. Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2017), 14.

[6] Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien, 42.

[7] Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien, 148.

[8] Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien, 47.

[9] Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien, 162.

[10] Tolkien, Beren and Lúthien, 137.

[11] JRRT, The Silmarillion, 186.

[12] JRRT to Christopher Bretherton, July 16, 1964, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 257; and JRRT to Christopher Tolkien, July 11, 1972, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 340.

[13] JRRT to Christopher Tolkien, July 11, 1972, in JRRT Letters, Letter No. 340.

No comments:

Post a Comment