By Colin Duriez

https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2019/3-may/features/features/j-r-r-tolkien-rapturous-words-that-inspired-a-whole-world?fbclid=IwAR0uIcuFsXUCgabPuVGIjRi31Vvl_VnVrRbYLe-hcdqDMoW9uYNc_rL5f7I

3 May 2019

The Light of Earendil

IN A letter, J. R. R. Tolkien once described himself: “I was born in 1892 and lived for my early life in ‘the Shire’ in a pre-mechanical age. Or more important, I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories), and in fact a Roman Catholic. The latter fact cannot be deduced. . . I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size).”

Tolkien is known throughout the world, mostly for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the books and the films. He is not so well known, however, for the many books published after his death, which mainly concern the earlier ages of Middle-earth, right back to its creation. The more familiar stories are located very late in the Third Age of that world.

It is also less known that all the stories, familiar or unfamiliar, are set not only in the changing landscapes of Middle-earth, but also in a mythology that Tolkien spent most of his life developing. He believed that his created legends were inspired by a medieval Christian world-view, and the northern paganism that it had absorbed.

Tolkien did not assume a knowledge of Christianity on the part of his readers when writing his tales of Middle-earth. In fact, many readers are probably unaware that his Christian faith was central to his writings. Indeed, he would have continued his mythology even if most of the world was non-Christian.

His created world and its symbolism was not allegory — designed to be interpreted by Christian teaching — but a fresh way of seeing reality which prepared the ground for the Christian gospel, if his readers encountered it. Tolkien also believed that the character of God’s image in all of us responds, unless stifled, naturally to authentic fantasy and fairy tale, because it has not been totally destroyed by evil.

THE shaping seed of Tolkien’s mythology, and the world of Middle-earth which his imagination built, lies in a single medieval poem that he read as an undergraduate in an Oxford university library, not long before the outbreak of the First World War.

He had become an orphan nearly a decade before, when his mother died. A caring priest from the Birmingham oratory, Fr Francis Morgan, had become his guardian, and the oratory was the spiritual home for him and his brother, as it had been before for his widowed mother.

For Tolkien, hope was important. While reading the eighth-century poem by Cynewulf named Christ— part of his required reading — he became rather excited by some lines:

Éala Éarendel engla beorhtast

ofer middangeard monnum sended.

ofer middangeard monnum sended.

These can be translated as, “Hail, Éarendel, of angels the brightest, sent over middle-earth to mankind!”

Tolkien was fascinated by the name “Éarendel”, which took him back in time, he felt, “far beyond ancient English”. From these words he came to detect a hint of a buried mythology in Old English language. In later years, he described them as “rapturous words from which ultimately sprang the whole of my mythology”.

TOLKIEN grew to believe that it was inconceivable to have a mythology without language, or language without a mythology.

Writing in Le Monde, days after the author’s death in 1973, George Steiner discerned that Tolkien had made his “great discovery” as an undergraduate: “The basic design of a grammar is a lifeless thing without a mythological content, without the image of a partly real and partly imaginary world which gives human speech its vital mixture of communications and secrets.”

This early conviction became “one of the main features of his thinking — that all creation contains the vestiges of a mythology. . . To study the grammar of a language, particularly an ancient or partly lost language, is to engage in mental archaeology. . . The philologist and the grammarian bring out to the light of day the conventions of dreams, the fundamental concepts of art, the historic memories of a buried world.”

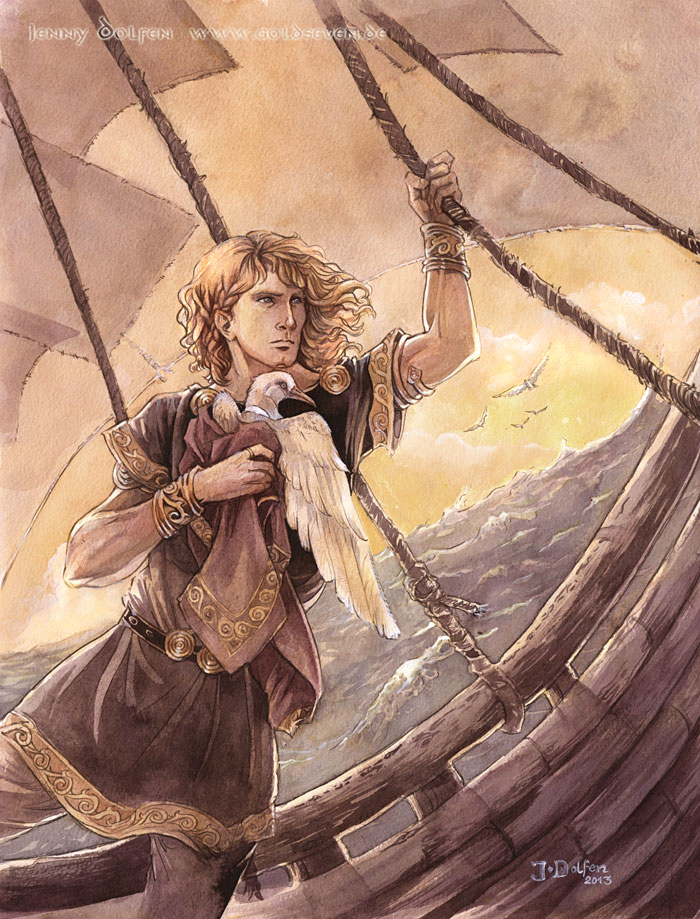

Earendel the Mariner by Jenny Dolfen

A LOOK at Tolkien’s treatment of Éarendel can help us to see how this discovery, married with his Christian imagination, shaped the writing that so many love today.

In Cynewulf’s Christ, Éarendel is a John the Baptist figure, the herald of Christ’s coming. In Tolkien’s mythology, as he later explained, he became “a prime figure as a mariner, eventually as a herald star, and sign of hope to men”. Eärendil the Mariner, who represents both elves and humans, and “sprang up from the Ocean’s cup In the gloom of the mid-world’s rim”, is an ambassador, interceding for the rescue of the exiles in Middle-earth.

A consistent motif in the story of Eärendil, and his descendants in later tales, is light. Eärendil is hailed as “bearer of light before the sun and moon! Splendour of the Children of Earth, star in the darkness, jewel in the sunset, radiant in the morning!” He is also hailed as “brightest of stars”.

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger is among those who have deduced that this use of light in The Silmarillion derives from the author’s Christian belief.

Another central theme is providence. For Tolkien, myth pointed forward to fact. The ages after the period of The Lord of the Rings would be marked by the coming of Christ, heralded in the return of Aragorn the king.

Fundamental to Tolkien’s mythology is the fact that the demiurges or powers, the gods involved in the creation of the world — the Valar — are themselves creatures of Ilúvatar, the one God. The divine providence thus overrules all principles and powers found in created reality, including the forces of evil.

This complex pattern of free will and providence is captured when Sam, Frodo, and others look in the mirror of Galadriel. It shows not only what will happen, but also what might happen. Events in Middle-earth are not “closed” but “open”; free will has a bearing on the outcome of events. Sam and Frodo choose to go to Mordor. The audacious strategy of seeking to destroy the Ring under Sauron’s nose depends on freely chosen sacrifice and a deliberate act of apparent foolishness. In the Third Age, wizards arrive in Middle-earth — one of whom, Gandalf, makes an act of providential sacrifice.

Prophecy is also important. In The Lord of the Rings, we learn that the king returning to Gondor will be recognised by his healing hands. Aragorn’s broken sword fulfilled another prophecy.

By the time Tolkien went to war, he had already begun to create his world — his imagination sparked by Cynewulf’s poem. He was soon thrown into one of the bloodiest battles of the war, at the Somme, in which one of his closest friends was killed on the first day. Another friend was wounded as the battle was ending, in November that year, and died a few days later. Tolkien was devastated. He later wrote: “A real taste for fairy-stories was wakened by philology on the threshold of manhood, and quickened to full life by war.”

Succumbing to serious trench-fever, Tolkien was returned to England to convalesce. By 1917, he had drafted the first story for his mythology of Middle-earth, “The Fall of Gondolin”, featuring the heroic father of Eärendil, Tuor. More than 50 years later, Tolkien was still trying to complete his mythology when he died.

WITH a renewed interest in his life and work, let us remember Tolkien’s lifelong Christian faith, and resulting commitment to the imaginative world that he devised: a sub-creation in the image of God’s creation. Let us also remember its inspiration from that poem written more than 1200 years before, which heralded a future that knows the healing and renewing love and self-sacrifice of Christ. Without that future kingdom, there is only the inevitable domination of darkness, which Tolkien had glimpsed in the horror of war.

Perhaps Tolkien’s life’s work as a Christian and a mythologist is like a bright star — another herald, sent over the world to humankind. Tolkien’s hope was that those readers who did not know his faith, and what his mythology heralded, would be prepared for recognising the gospel, if it came in grace to them.

Colin Duriez is the author of a number of books on the Inklings, including J. R. R. Tolkien: The making of a legend (Lion, £8.99).

No comments:

Post a Comment