By Nathanael Blake

https://thefederalist.com/2019/04/26/exploring-irish-ancestry-taught-michael-dougherty-nationality-matters/

April 26, 2019

Nations matter because we mortals matter. Because we are finite, we must reside within particular communities and find fulfillment in them. Thus, if we matter, so do our communities, including our political communities.

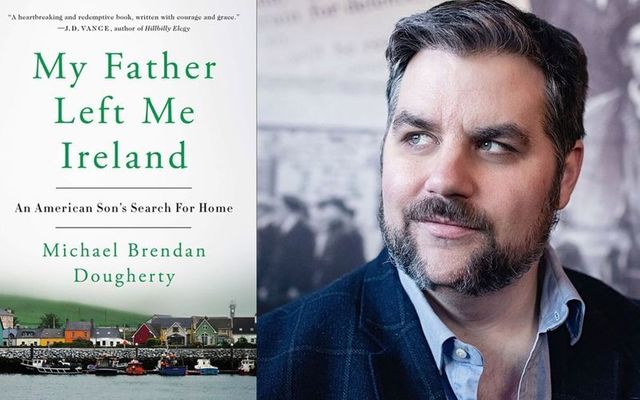

This is among the lessons of the excellent new book, My Father Left Me Ireland: An American Son’s Search for Home, by Michael Brendan Dougherty of National Review. This slight volume is part memoir, part political and cultural reflection, intermingled and woven together. Styled as a series of letters to the Irish father who was absent during his childhood, it offers a compelling case for the importance of nations and nationality.

His reflections begin with the too common experience of an absent father, each of whose visits he recalls as “A brief, suggestive interruption of a life I lived without you.” During his teens, he eliminated even this sporadic contact, cutting his father out of his life and refusing to respond to his letters.

But his father’s absence did not sever all ties to his father’s homeland. Dougherty writes that “My mother wanted me to know myself as Irish.” So as a child he learned a little Irish language and more Irish history. As he grew up, the political landscape changed in Ireland, but there was still plenty of Irish schlock to consume. For the diaspora, Irish identity was something to put on or take off.

A Plastic Paddy

These were shallow identities, so as an adult, he felt himself to be Irish only in “the most technical and bureaucratic sense.” He could claim an Irish passport if he wished, but he would still be a “plastic Paddy. A Yank. A tourist who stumbles on a ruined castle and thinks it’s the old family homestead.”

The impending birth of his first child pushed him to his roots, for “It occurred to me that in a few months I would have this life wriggling across my lap. I would have to tell her who she is…I am suddenly alive to the idea that I could pass on this immense inheritance of imagination and passion if I could only work up the courage to claim it for myself.” His daughter (and subsequent children) could know themselves as Irish-Americans in a real sense, rather than the attenuated, Guinness and “Kiss me I’m Irish” T-shirt for St. Patrick’s Day fashion.

But why? Why sing rebel songs as lullabies and teach his children the Irish language, especially in America? Why struggle to impart an Irish identity that is being abandoned even in Ireland?

Dougherty’s embrace of his Irish heritage arose in part from the hollowness of the American culture he grew up in near New York City. Identity was something he was to create for himself, not a patrimony he was to preserve.

Growing up in the ’90s, he saw that adults were “terrified of having authority over children and tried to exercise as little of it as practicable … The constant message of authority figures was that I should be true to myself. I should do what I loved, and I could love whatever I liked. I was the authority.” The past had no imperatives for the present; its shackles had to be broken and either discarded or used as raw material for the future.

Raised on this “myth of liberation,” Dougherty was told to create himself, enjoy himself, and to protect himself. He was encouraged to keep an ironic distance and to take nothing in earnest except enough sensible self-protection to avoid ruining a future career. Stay aloof, keep options open, and remember that sincerity is vulnerability.

The Myth of Liberation

s a young man he found this “curator’s approach to life” congenial. He applied it to Irish culture, which he saw not an inheritance “to be treasured and passed on, but … ornaments of a life defined by enjoyment, consumption.” Know some history, read some Joyce, make a bit of Ireland part of a personal brand. Even his return to the Catholic Church (brought about, ironically, by a Baptist girlfriend) partook of this spirit of detached irony and self-creation.

In a curated existence, authenticity becomes currency, so the detached culture Dougherty describes was the prelude to our identity-mad present, brought about because the solvents of liberalism have erased inherited identities in all their particularity. It left us selecting identities as if we are choosing consumer goods. Heritage has become a form of branding, something to be bought and sold.

Many of the current excesses of identity political and “wokeness” are reactions against this. Cultural appropriation is hated as a manifestation of identity as commodity. Victimhood is cherished because suffering for an identity confirms authenticity.

But this shift from irony to identity has not repaired the damage done to pre-liberal identities. Those who wish to claim an identity are left constructing them from the fragments of a shipwrecked heritage. The communities and relationships that provide support, comfort, and meaning in life are still being eaten away by the acid of absolute individual autonomy. The early decline and death of his mother brought this into focus. Dougherty found that

This myth of liberation was like a solvent that had slowly and inexorably dissolved any sense of obligation in life. It dissolved the bonds that held together past, present, and future. It dissolved the social bonds that held together a community and that make up a home. And, here at the end of the process, I was alone … A healthy culture provides all the proper ceremony for death, it gives rituals that allow people to grieve as individuals, and families. But in an age of self-creation, of a curated life, lived in row houses where people hardly know their neighbors, the bereaved are confronted with an endless series of menus and options.

It is against this expanse of empty consumerism that Dougherty is trying to assert his Irish identity. Yet the Irish are embracing this same hollowness. In the end, the English won over the Irish, as Irish identity is being revised into erasure and the Irish want to be just another European nation.

Nationality as Inheritance

In liberal political theory, the nation is viewed as a useful but problematic administrative unit. The particularity of a nation is troublesome, insofar as particulars are necessarily exclusive. Against this attitude of cosmopolitan liberal technocracy, Dougherty sets the immediate failure and eventual vindication of the Easter Rising.

He asserts that “nations have souls … the life of a nation is never reducible to mere technocracy … nationality is something you do, even with your body, even with your death.” Nationality is an identity that matters. It should not be effaced to make way for ever-larger empires of liberalism.

Thus, he writes that the effort to preserve the Irish language “took on the character of a voluntary and local resistance to globalization and the reordering of all culture by commerce. Its preservation required the courage to embrace an identity that could not be bought and sold.” So he has launched himself into an effort to learn the Irish language, and to pass it down as an identity and inheritance to his children.

A critic might dismiss this as so much romantic nostalgia on Dougherty’s part. It could be attributed to the childhood absence of his father, followed by teenage estrangement and adult reconciliation. It could be an overreaction to his mother’s early death and the birth of his own children. Psychologically, the critic might have a point; this is a personal story insofar as these factors led Dougherty to his conclusions.

But what alternative would the critic offer? The liberal, technocratic project offers autonomy, entertainment and comfort, but these do not content us. “Why Ireland?” may be answered by the particularities of Dougherty’s life.

Why nationalism?—a resurgence of which is tormenting Western liberal elites, is not so easily explained away. The attempt exposes the failures of technocratic liberalism, especially its inability to provide for the deepest human needs and its destruction of the relationships and institutions that can.

Man does not live by bread alone, nor even by pizza and Netflix. Rather, we find meaning and contentment in relationships and community, which are particular and binding, rather than universal and liberated. We realize our true identities, in our finitude and particularity. Commitment rests on particularity and permanence: this instead of that.

Pilgrims on This Earth

Recognizing this reveals the culture of liberal autonomy and indulgence as an attempt to avoid our particularity and therefore our mortality. We are, as Christianity teaches, pilgrims on this earth precisely because we are particular and finite beings who will one day die. The church is called to be universal; we are to be particular parts of it, and we should love the communities we live in, including our political communities. An important part of that love is caring for those who will come after we are gone.

But liberalism encourages us to consume instead of leaving an inheritance for those who will live after us. As Dougherty puts it, “We are great consumers. We are useless as conservators.” From our furniture to our houses to our politics, little is built to endure. We build convention centers, not cathedrals.

Nonetheless, we have plenty—for the present. No wonder we are so anxious. Our culture disdains not only the Permanent Things, but also the permanent things that remind us of our mortality and make us look to posterity. The longing for the old country (where the Guinness is better) and the old family homestead can be silly, but it illuminates the real need for solidarity between generations.

Dougherty writes that the “ghosts of a nation reproach the living on behalf of posterity.” But we are increasingly cut off from both past and future. It is no coincidence that those who disdain their progenitors tend to disdain their progeny, and he adds that “When we do have children we so often have them as consumable objects, as part of our lifestyle choices. We do not receive them as gifts, as living things, inviolate and inviolable. We calculate about them, not worried over what we might give them, but what they take from us.”

Liberal individualism sees children as potential burdens, high-maintenance consumer goods. Communities, from families to churches to nations, see them as fulfillment.

People are the point of it all, and people exist in particular times and places. To reduce the nation to an instrument of technocratic administration is to reduce persons to livestock. It is as demeaning and dehumanizing as the error of entirely subsuming the individual to the interests of the state. Care for people requires care for the particularities of the communities they live in, including political communities, with all their heritage, joys, sorrows, and troubles.

Nathanael Blake is a Senior Contributor at The Federalist. He has a PhD in political theory. He lives in Missouri.

Related:

No comments:

Post a Comment