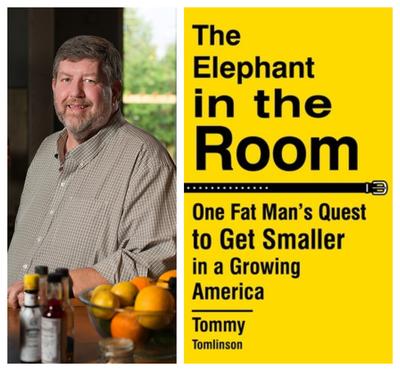

Longtime ‘Charlotte Observer’ columnist writes about his struggle with weight — but this isn’t your typical sunny-side-up read

STEPHEN RODRICK

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/elephant-room-tommy-tomlinson-memoir-779176/

January 16, 2019

A few years ago, I was in Charlotte, North Carolina and a mutual friend suggested I look up Tommy Tomlinson, a longtime Charlotte Observer columnist who was transitioning from the paper to becoming one of America’s best longform sportswriters. Tomlinson proposed lunch at a Greek restaurant not far from my hotel.

Not knowing the city, I arrived about 15 minutes early. The fiftyish Tomlinson was already there, sitting squarely in the middle of a booth. We had a nice lunch, but I felt that Tomlinson, a Falstaffian-sized man with twinkling eyes was going to leave many great stories untold. Even getting out of the booth was an effort, with Tommy breathing heavily after a difficult extraction. It was the middle of the day, but he already looked exhausted.

I left wondering why he had arrived so early. I learned the answer just a few pages into The Elephant In The Room, Tomlinson’s heartbreaking and self-lacerating look at his life as a man who hates himself for tipping the scales at 460 pounds. Turns out that one of the trials of being a man of his size is he has to scout restaurants for seats that will support him. The Elephant In The Room begins with Tomlinson on a rare trip to Manhattan. Between fearing he will crush an old woman on the subway to his dread of a chair collapsing when he meets someone at a diner, he is in a near panic. He must advance the restaurant like a campaign aide working a political campaign.

“I scan the space like a gangster, looking for danger spots,” he writes. “The booths are too small — I can’t squeeze in. The bar stools are bolted to the floor — they’re too close to the bar and my ass would hang off the back. I check the tables, gauging the chairs. Flimsy chairs creak and quake beneath me. These look solid. I spot a table in the corner with just enough room. I sit down slowly — the chair seems OK, yep, it’ll hold me up. For the first time in an hour, I take an untroubled breath.”

This is just another day in the life of an obese man in America, a country where instead of lampooning ex-New Jersey Governor Chris Christie for his microscopic approval ratings we go straight to the fat jokes — even though, as Tomlinson cites, 79 million Americans can now be considered clinically obese.

Tomlinson came to his weight through a combination of genetics and circumstance. His parents came from sharecropping roots where food was consumed greedily when possible, as if storing away for another depression. As times improved, plentiful food became the tangible sign of progress and, as Tomlinson writes, “Everybody in my family was an artist when it came to Southern food.” His family medicated and celebrated in good times and bad with fried chicken and his sister’s patented Christmas peanut-butter log. The only vegetables on the menu were swaddled in butter or cream.

On his own, Tomlinson confesses to spectacularly bad eating with decades of Wendy’s double cheeseburgers replacing Proust’s madelines as memory signposts. As a frequent guilt-ridden partaker in Taco Bell, I was overjoyed when Tomlinson tartly pointed out the reason people eat fast food is not only for cheapness, but because it’s a diabolical combination of processed sugar, salt and fat that launches pleasure chemicals in our brain. Once you’re hooked, it’s as hard to kick as Ray Liotta’s pre-Chantix cigarette addiction

Tomlinson began to reassess his life in 2014 after the death of his 63-year-old sister Brenda, who died because of MSRA infection after years of declining health tied to her body weight. He hates himself for all the things he has not done, from swimming to hiking to skateboarding. (Well, he didn’t miss much with skateboarding). He knows he’s let his wife down in the bedroom by simply not having agility or energy. He writes of never having great dreams, reasoning if he can’t manage this one bit of self-care there is no way he is going to accomplish anything on the big stage.

Still, he tries to understand why a man who wrote columns on deadline for a living and built a stellar career in a dying industry can’t say no to bad food. (One of the ways you know this isn’t your sunny-side-up inspirational memoir is each chapter includes Tomlinson’s weight through 2015 and, for most of the time, he loses next to nothing). He would do ok for a few days, but then he’d be back at the drive-through where the cashier could finish his order just from recognizing his voice.

What could have been a wallow in memoir self-pity is raised to art by Tomlinson’s wit and prose. Yes, he examines the external causes for his weight — family, America’s tyranny of choices and temptations, not to mention the solace it gives him when fat-induced loneliness strikes. But he is hardest on himself, admitting he never met a couch he didn’t like and an exercise he couldn’t despise.

“Every body perseveres in its state of rest . . . unless it is compelled to change,” he writes. “Newton’s first law is also known as the law of inertia. It is the one law I have followed with devotion….The law is meant to describe the physical world. But inertia works just as hard on my mind. My willpower has been an object at rest longer than anything else. It is my weakest muscle.”

After yet another backslide, Tomlinson has a sleepless night and a dialogue with himself. Does he have a death wish? Does he want to check out before his beloved wife so he doesn’t have to relive the agonized grieving he felt after losing his sister? Maybe. But in the end, he settles on a less sympathetic take that plagues men of a certain age whether it is eating, dating women half their age, or being the oldest dude at the kegger: He doesn’t want to become an adult writing “Grown-ups watch what they eat. Grown-ups exercise… Grown-ups are honest with other people and with themselves. The boy inside me says: Fuck that.

Armed with that simple but oft-ignored revelation, Tomlinson moves forward, but it is trench warfare measured in inches, a highlight is being able to fit into a 4XL shirt at Walmart. There’s none of the rhetoric of ridiculous diet ads where a famous man holds out his empty pants implying if you drink this powdered drink you will lose a foot off your waistline.

The greatest asset of The Elephant In The Room is that Tomlinson frames his struggle in a way that makes it universal, whether your downfall is food, an exciting but disastrous life partner, or some other unconquerable temptation. By the end, Tomlinson doesn’t so much defeat his obesity, as battle it to a well-understood draw. Days are won days are lost. For most of us, that’s the best-case scenario.

No comments:

Post a Comment