By Glenn Kenny

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/03/movies/icarus-netflix-russia-olympic-doping.html?action=click&module=RelatedCoverage&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer

August 3, 2017

In November, the disgraced former cycling champion Lance Armstrong will go to trial in a civil fraud suit related to his use of banned performance-enhancing drugs. A recent report in USA Today suggests that Mr. Armstrong may pursue an “everybody does it” defense, and goes on to describe the Justice Department’s strategy to block that plan. Whatever the fate of Mr. Armstrong, it seems that the sad fact of the matter is that an “everybody does it” argument has legs, so to speak.

The filmmaker Bryan Fogel recently reminded me that the practice of doping goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, who in their own Olympic Games would drink drug and herb concoctions to kill pain. A few years ago, Mr. Fogel, a filmmaker and a dedicated amateur cyclist who had, like so many, idolized Lance Armstrong in the years when he vehemently denied doping, had an idea for a movie on the theme: He would create a doping regimen for himself that could go undetected and record the results of the experiment.

“I had initially conceived this as a movie like ‘Super Size Me,’ in which I’m the subject of this experiment to expose the failure of antidoping systems,” Mr. Fogel said in a phone interview. “Ultimately the question would be, what is the good of this system that’s supposed to police doping if it can be defeated like this?”

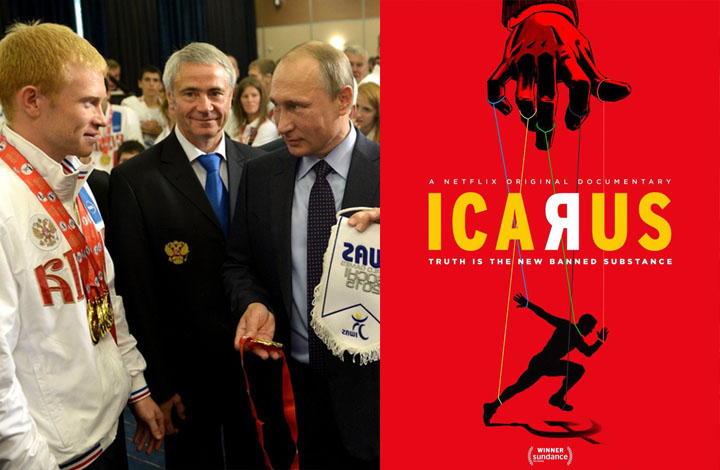

Had things gone according to plan, his film, “Icarus,” available for streaming on Netflix on Friday, Aug. 4, might well have ended up a persuasive albeit dispiriting account of how easy it is to mask the use of performance-enhancing drugs. But a world sporting scandal intervened, making Mr. Fogel’s story more suspenseful and more disturbing.

“Icarus” begins with Mr. Fogel describing his lifelong cycling obsession as a largely masochistic one. Having cycled without using such drugs his whole life, in the wake of the Lance Armstrong scandal he decides to cheat and consults a man who has devoted his life to finding cheaters — Don Catlin, a scientist who invented many of the protocols for contemporary drug testing in sports. Dr. Catlin assists Mr. Fogel for a while and then refers him to his Russian counterpart, Grigory Rodchenkov.

Initially, Dr. Rodchenkov comes off as an eccentric. Bluff and voluble, he conducts Skype calls with Mr. Fogel while shirtless. He dryly refers to his homeland as “the most relaxing place in the world” during Mr. Fogel’s visit to Moscow, after Mr. Fogel has had enough experience to know it’s more likely the opposite.

Strangely enough, Mr. Fogel’s doping doesn’t help him in the next amateur event he competes in. But then the story takes a harrowing turn. Mr. Rodchenkov participated in what the film calls “a systematic, statewide system to cheat the Olympics” — specifically the 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia. The story explodes in the late fall of 2015, and Dr. Rodchenkov, fearing for his life, is compelled to leave Russia. A late-night call to Mr. Fogel seeking the filmmaker’s help in getting him out of the country is in the movie.

“That wasn’t part of the scheme,” Mr. Fogel said. “When you see me helping Grigory get out of the country, I’m doing it, I’m putting it on my credit card, everything.” At that point, Mr. Fogel said, he had to go back to the movie’s investors and tell them that what started as a meta-exposé with himself as a guinea pig was going in a very different direction.

Suddenly, Mr. Fogel was in constant consultation with lawyers and journalists — including ones from The New York Times, which ran an interview with Dr. Rodchenkov in May 2016, one of many articles on the subject. “Icarus” eventually goes into jaw-dropping detail about the elaborate urine-swapping scheme that enabled large-scale cheating at the Sochi Olympics, where Russian teams won 13 gold medals (the country received 33 medals over all), much to the delight of Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin.

“It’s very important to Russia, its national identity, and this is particularly true of its national identity under Putin, that it be a dominating force in sports,” Mr. Fogel said.

“Icarus” has archival footage from the 1970s in which Dr. Catlin shares ideas with a contingent of Russian doctors visiting his labs in California — one of whom is Mr. Rodchenkov.

“In a sense, Grigory was there as a spy!” Mr. Fogel said. “Assume that Russia has been doing this for 40 years and that Sochi was just the icing on the cake. Think about it: They were robbing the bank, and they owned the bank. They spent $50 billion to create Sochi. What they had at stake was showing Russia as a world power in sports.”

All of which brings up a timely question: How far will Russia go to achieve other goals? As for Mr. Rodchenkov, in “Icarus” he evolves from an eccentric character into a courageous man who is forced to make some difficult decisions. For about a year now, he has been in protective custody in the United States. His wife and children remain in Russia, unable to travel because their passports have been confiscated. Mr. Fogel has been able to screen the film for Mr. Rodchenkov and is still concerned about the state of his friend’s case. “I really don’t know what the government has planned for him or how this is going to resolve,” he said.

The global implications of Mr. Fogel’s topic makes Netflix’s reach appealing. “No other company can press a button and get your movie out to 190 countries,” he said. Mr. Fogel does not intend to go back and make his own “Super Size Me,” despite some of the questions about doping in both amateur and professional sports that the movie leaves open. Does everybody really do it? If so, what does the term “fair play” even mean anymore? Would play be more fair if it were allowed? And given the conditions, would permitting a practice we consider corrupt be not just more expedient but somehow morally justifiable?

No comments:

Post a Comment