Reagan in the Wilderness

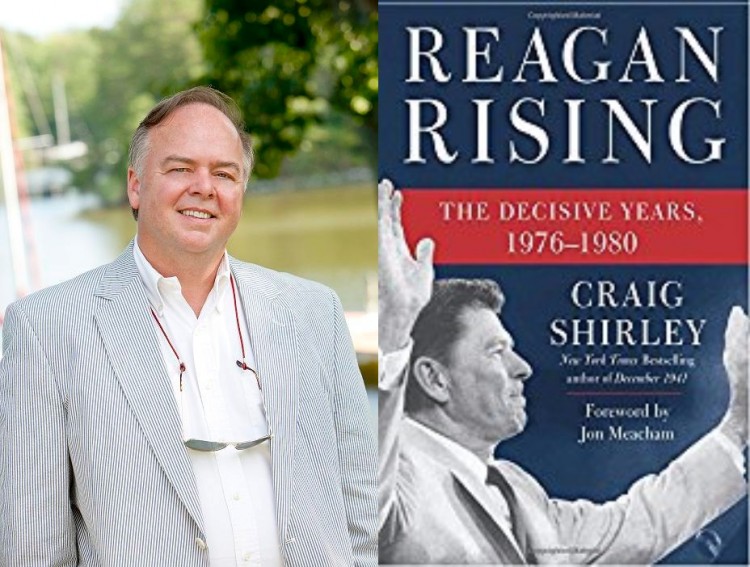

Reagan Rising: The Decisive Years, 1976–1980, by Craig Shirley (Broadside, 432 pp., $29.99)

Thucydides had a great advantage over later historians in telling his tale of the Peloponnesian War: As a general in the Greek army, he had been there. Craig Shirley, who is emerging as the most prolific and, in some respects, most insightful chronicler of Ronald Reagan’s political rise, shares that advantage. He was there.

As a young political operative, in roles ranging from press secretary for the surprise winner of a long-shot U.S. Senate bid to a similar position with a prominent governor to heading up a pivotal independent-expenditure committee backing Reagan in 1980, again and again Shirley was perfectly placed to see and understand all that went into one of the most remarkable — and, once in office, successful — political careers in American history.

In earlier volumes, Shirley detailed Reagan’s failed 1976 run for the presidency, his successful bid four years later, and his twilight years after leaving the nation’s highest office following two terms comparable in achievement only to those of Washington, Lincoln, and FDR. Now Shirley has taken on the 40th president’s equivalent of Winston Churchill’s “wilderness years” — the time out of office, when many doubted his ability to return in any serious way to the stage, much less take center stage. This was the period when Reagan’s culminating run for the presidency was born.

While it revolves around Reagan, Shirley’s story also focuses on three other men — Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and George H. W. Bush.

It is widely forgotten now how bitter the division between the Ford and Reagan forces was in the mid 1970s. Shirley takes readers through a compressed account of the 1976 campaign for the GOP nomination — “the tightest two-way race for a major-party nomination in modern political history,” Newsweek (quoted by Shirley) called it — and the fall campaign that followed. Some thought that after Reagan’s strong challenge, Ford should offer him second spot on the ticket. Such was the personal animosity that Ford refused.

With his brilliant, semi-extemporaneous speech on the convention’s last night and impressive appearances before state delegations over the previous week, Reagan emerged as, in the words of prominent columnist Jack Germond, the GOP’s “heir apparent.”

Yet Ford was far from out of the game. He disliked Reagan, who represented a rising but, in the view of moderates, dysfunctional part of the party, and he felt that Reagan had not given his full energies to the general-election campaign, facilitating Carter’s victory. Reagan in turn was disgusted at Ford’s hardball tactics during the nomination fight and opposed Ford’s moderate-Republican approach to the Soviets, the economy, and much else. The rivalry hung over the Republican party even into the 1980 GOP national convention in Detroit. As Shirley tells it, on Carter’s inauguration day, as Ford “jetted off to California” after the ceremonies, he “told a reporter, after dining on shrimp and steak and a couple of dry martinis on the 707 that had been designated Air Force One when he was president, that he was game for another try at the White House in 1980 and that ‘I don’t want anyone to preempt the Republican presidential nomination.’” “Anyone” meant Reagan.

Shirley is surprisingly sympathetic to Carter, who, like Reagan, was cut from populist cloth. As he explains:

Rural populism had sprung up in Carter’s South and Reagan’s Midwest in the 1890s, and was mostly focused on the power of moneyed eastern interests, especially large banks, railroads, and manufacturers. . . . Big government was also a focus of populists’ ire, which Carter acknowledged. . . . Though some racists were involved in the populist movement in its earlier years, both Carter and Reagan abhorred racism.

Shirley highlights another similarity between Carter and his successor. Washington, he says,

did not understand how close Carter was to his wife, Rosalynn. They underestimated this steel magnolia, and for the oft-divorced sophisticates who made up the Washington intelligentsia, such personal closeness between married couples was deemed peculiar. . . . A cultural rift was developing between the uncomplicated Georgians and the unctuous Georgetowners, who would bedevil Carter all through [his presidency].

But though, in cultural respects, they were more like each other than like the establishment of the federal city, Reagan and Carter could not have been more unlike in politics or political ability. Reagan celebrated the American spirit and the American character and looked to restore vibrancy to an economy that was increasingly enmeshed in stagnation and inflation. Carter was soon looking to impose a heavy tax on gasoline, halt dozens of western water projects, and embrace an era of limits. Within months of Carter’s inauguration, columnist George Will would write that he had “opened a multi-front war on numerous American practices, habits, and mores.”

At about the same time, Carter, who had suggested during his campaign that Nixon’s détente policy was too weak-kneed, lectured Notre Dame’s commencement audience to beware of what he called an “inordinate fear of Communism.” Soon he was calling for normalization of relations with China, Cuba, and Vietnam, even as he was cracking down on authoritarian regimes that were, nevertheless, American allies.

Reagan bristled at all of this, but it was Carter’s signing of the treaty (largely negotiated under the Ford administration) turning control of the Panama Canal over to the Panamanian government that gave him an opportunity to act. Almost alone among major American political figures, he opposed the pact and campaigned against it — and though the pro-treaty forces prevailed in the Senate, Reagan won in the country. The nation had seen a man unafraid to take on all comers in defense of what he saw as right.

Despite numerous hints and feints over the next two years, Ford never entered the 1980 race. Instead former congressman, ambassador, Republican National Committee chairman, and CIA chief George H. W. Bush emerged from a crowded field to become Reagan’s chief rival. In 1979, Bush campaigned vigorously and effectively while Reagan stayed off the campaign trail, skipping major events and sticking to his radio commentary, columns, and paid appearances. The reason for this reticence was John Sears, Reagan’s 1976 campaign manager and the man initially in charge of the 1980 run. Shirley is highly critical of Sears’s strategy of aloofness, which came within a breath of killing Reagan’s candidacy.

Across the nation and particularly in Iowa, Bush and his impressive and equally energetic family were everywhere, with the result that Bush won the Iowa caucuses. The next big prize was New Hampshire, five weeks after Iowa. Losing patience with Sears, Reagan took control of his organization and campaigned even more intensively in the Granite State than Bush. Then, the Saturday before the primary, in a showdown debate with Bush, Reagan displayed the same steel and fire that had marked his Panama Canal advocacy. As a local newspaper editor, who was the debate’s moderator, tried to turn off his microphone over a dispute about the role in the debate of other candidates, Reagan, who was sponsoring the forum himself, sternly stopped him with the now famous remark, “I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green.” By Tuesday night, the nomination was all but in Reagan’s hands.

As he concludes, Shirley offers this assessment of his subject:

Reagan remains one of the most fascinating figures of history and the American presidency, in part because he was a constantly evolving individual. His worldview in 1964 was not his worldview in 1980. His conservatism had changed, from being simply against the intrusion of big government to the more positive advance of individual freedom.

Reading Craig Shirley has become essential for any Ronald Reagan student. Reagan Rising strengthens his already high standing among Reagan biographers.

– Mr. Judge is the managing director of the White House Writers Group and the chairman of the Pacific Research Institute.

No comments:

Post a Comment