The guitarist loved AC/DC, the singer loved country. Live, their combustible union was a total blast, but this Nashville band couldn’t sustain the momentum

Michael Hann

http://www.theguardian.com/

April 12, 2016

There are only ever a handful of names that get mentioned when the idea of “the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world” is raised. Actually, there have been dozens of greatest rock’n’roll bands in the world, but most of them never get recognised – because they were only ever the greatest band for a week, or a month, a summer. They were the greatest band at some point where everything aligned for them – they had a great record out, their shows were on fire, the crowds were going wild. Everything they touched, they torched. A very few – through their own cunning, the machinations of their label and management, the support of radio – are able to seize that moment, to capture that momentum, and move on to greater things, to platinum records and stadium shows. Most, though, for whatever reason, will have only the brief moment of transcendence, before they slip back into the ranks. The shows will get smaller again, the records less inspired, the fire will burn less fiercely.

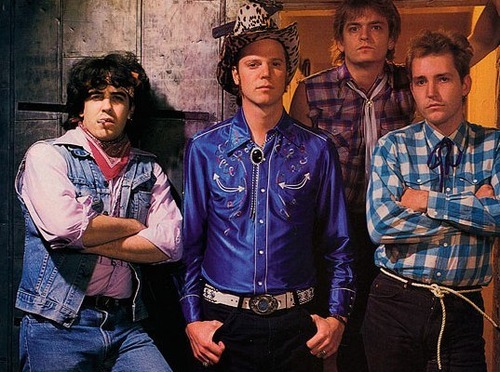

In summer 1985, Jason and the Scorchers were the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world. On 4 July that year, I saw them headlining an Independence Day bill at the Electric Ballroom in London, above the Blasters and the Textones. I was in the front row, and even the distance of 31 years has done nothing to dull the memory of how combustible they were. Singer Jason Ringenberg whirled around the stage in a frock coat and cowboy hat, his legs jerking behind him as if he were getting electric shocks from the mic stand; guitarist Warner Hodges wheeled in circles, without ever missing a power chord; bassist Jeff Johnson, in pressed shirt and bolo tie, looked like a Victorian riverboat gambler by way of the New York Dolls. The mini Confederate flag flying from drummer Perry Baggs’s spare rack top slot didn’t raise the #problematic signals it might now.

Ringenberg was a pig-farmer’s son from Illinois who moved to Nashville in 1981, with the dream of forming a high-energy roots band. He didn’t realise rock’n’roll didn’t exist in Music City, but somehow stumbled across the other three, who brought the punk counterbalance to his desire to make country music. Hodges, whose parents were country musicians, had already had his fill of the twang – “He always said that country music was shoved down his throat, and he hated it,” Ringenberg told writer Clinton Heylin – but the tension between the guitarist’s desire to sound like AC/DC and the singer’s love of Hank Williams meant that, for the first few years of their career at least, Jason and the Scorchers made music that sounded like no one else, a berserk, overdriven racket, in which country covers and Ringenberg’s originals were played with Never Mind the Bollocks power by the other three.

The Scorchers’ vinyl debut came in early 1982, just a few weeks after their first show, with the Reckless Country Soul EP, featuring three Ringenberg originals and covers of Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers. They earned a fearsome reputation opening shows for whichever punk bands visited Nashville (“Because we were so explosive, it had such an energy and we attacked the stage so fiercely, they allowed the twang,” Ringenberg said of the punks’ attitude to the Scorchers), and became associates of the similarly upwardly mobile REM. In 1984, a new EP, Fervor (a cleaner and better recording, restating the premise of the band), featured vocal appearances from and a co-write with Michael Stipe. After they signed to EMI, a staggeringly exciting version of Bob Dylan’s Absolutely Sweet Marie was added, though it was only recorded because Ringenberg told Hodges it was an original; the guitarist wouldn’t have recorded it otherwise.

That summer of 85 high-water mark came off the back of the band’s full-length debut, Lost and Found, where Hodges’ guitars – given a modern studio and bigger production values – were finally allowed right off the leash, without suffocating Ringenberg in the process. Unlike most of their “cowpunk” peers, the Scorchers didn’t wrap their take on country in irony; Ringenberg’s love of his forefathers was palpable, and the rest of the band were so steeped in the music that they made Lost and Found sound as if it was always intended as an 180mph rush of speed.

As you’ll already have guessed, the moment of greatness was brief. The Scorchers became less Ringenberg’s band than Hodges’, as EMI ushered them towards big hair and big makeup, to go with the big guitars. If the Pistols at the Opry worked, Poison at the Opry most certainly didn’t. Their next album, 1986’s Still Standing, might have been better retitled Going Backwards. One more record, Thunder and Fire, and the Scorchers were no more. They reformed in the 90s, and still play live periodically, but the moment was gone – as fun as they might be, they would never again be the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world.

That 4 July, aged 15, I missed my last train home. I had to wait for the post train, then walk home from Slough station. I finally got back at around 5.30am – on a school night. My mother was still up, demanding to know why I hadn’t called. I said I hadn’t wanted to wake her, because it was midnight before I knew I’d missed the last train. No excuses, she said. She’d sent my dad up to Paddington to look for me; he got home just before he had to get up for work. It was the best part of four months before I was allowed to go to another show. Up at the Hammersmith Palais that night was another American band who were being called the “best in the world”; it was another desperate, thrilling show, albeit in a very different way to the Scorchers. But unlike Ringenberg et al, REM were able to turn their greatness into something that lasted. Maybe the Scorchers just weren’t built to last; I’m so glad I saw them when they were burning.

No comments:

Post a Comment