Randy Lewis

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/

September 24, 2016

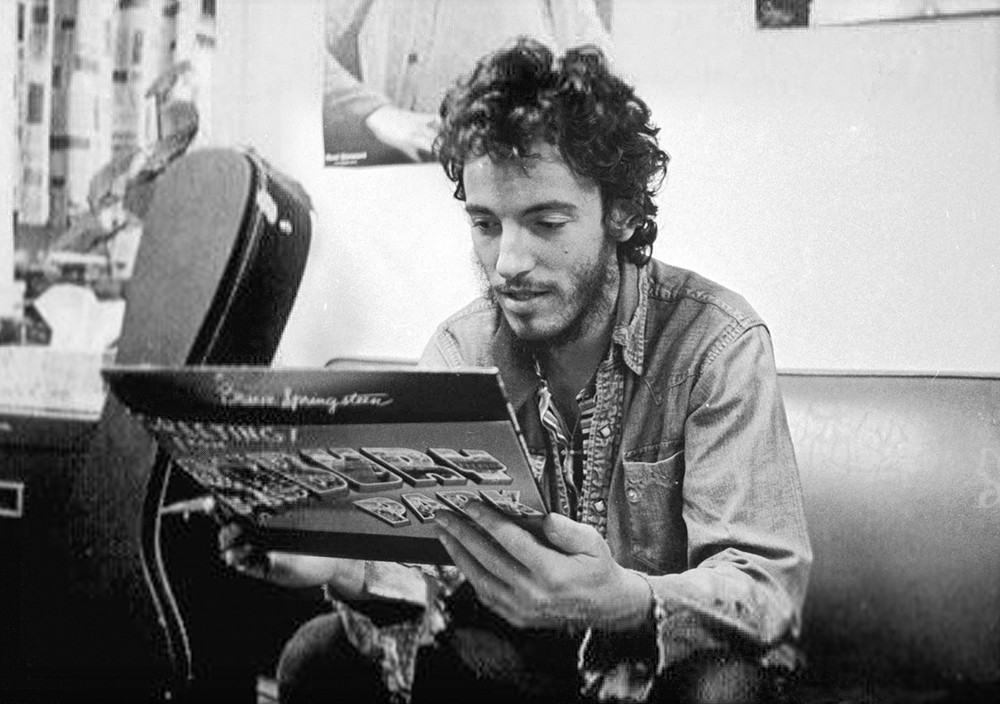

Anyone who has ever experienced the uniquely soul-stirring amalgam of musical celebration, spiritual rejuvenation, intellectual provocation and physical release-to-the-point-of-exhaustion that is a concert by Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band will feel right at home in the 508 pages of “Born to Run” (Simon & Schuster, $32.50), his 67-years (as of Friday)-in-the-making autobiography.

On the most superficial level, this richly rewarding rock tome could be subtitled “The Collected and Expanded Between-Song Sermons.” That’s how integral to his fabled marathon performances over the last 40-plus years are his ripped-from-New-Jersey-life fables of spirit-shaping battles with his father, his comradeship with his bandmates, his fitful attempts to unravel the mysteries of love and, binding them all together, his DNA-deep passion for music, specially that strain called rock ’n’ roll.

Throughout his career, the once scrawny kid who was born in Long Branch, N.J., and grew up in nearby Freehold, has relied on music as a source of inspiration, a platform for understanding the world around him and a forum for self-examination and expression.

All of those qualities serve this Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee beautifully in a book that illuminates not just the career, but the full-bodied life of one of pop music’s most valuable artists.

It’s alternately brutally honest, philosophically deep, stabbingly funny and, perhaps most important, refreshingly humble.

We’re told on the book jacket that his 2009 performance at the Super Bowl was what started him writing, specifically about that show and what it meant to him at the time.

“Since the inception of our band,” he writes late in the book about his group’s performance at the event that typically draws the largest global audience of any other, “it’s been our ambition to play for everyone. We’ve achieved a lot, but we haven’t achieved that.

“Our audience remains tribal...that is, predominantly white. On occasion,” he notes, “I looked out and sang ‘Promised Land’ to the audience I intended it for: young people, old people, black, white, brown, cutting across religious and class lines. That’s who I’m singing to today.”

It’s been his hubris from the outset that Springsteen believed to his soul that he had something to offer to the world; and his supreme gift that he fought and scraped his way onto stages across the globe to realize that dream.

Given his Catholic upbringing, it’s fitting that the book is divided into three parts, his own literary Holy Trinity, as he lays out his life story essentially in chronological order.

“In Catholicism, there existed the poetry, danger and darkness that reflected my imagination and my inner self. I found a land of great and harsh beauty, of fantastic stories, of unimaginable punishment and infinite reward. It was a glorious and pathetic place I was either shaped for or fit right into,” he writes early on. “This was the world where I found the beginnings of my song.”

Book One is titled “Growin’ Up,” recounting his early family life and apprenticeship as a budding musician; Book Two, “Born to Run,” continues with his rise to a level of fame and fortune he probably did conceive, but only in his wildest dreams, and Book Three, “Living Proof,” looks into adult life as one of pop music’s biggest stars, and the often diametrically opposed realities of his on- and offstage lives.

Unapologetic rock ’n’ roller that he is at heart, Springsteen often crafts chapters like good pop songs — most take just three or four minutes to finish, there are catchy hooks and typically snappy endings, usually with a grain of life’s truth dropped in along the way.

His book offers none of the surreal flights of imagination found in Bob Dylan’s unconventional 2004 memoir “Chronicles, Vol. 1” or Neil Young’s 2012 self-narrative, “Waging Heavy Peace.” And where Elvis Costello took readers on a trip through the formative events of his life processed through the filter of his formidable intellect in last year’s highly engaging “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink,” Springsteen speaks predominantly and most powerfully from the heart, and his gut.

roll for their own sake, but to illustrate

What emerges unequivocally is his almost singled-minded devotion not to scoring hits, or finding fame and fortune, but to creating a body of music that matters.

“Born to Run” also goes well beyond frequently illuminating analysis of his career ambitions, and the successful and unsuccessful execution of those aims to paint a picture of a full-rounded life, with all its rough edges, bruised and battered relationships and another theme that’s been ongoing in his music: the redemption that’s possible to those who seek and are willing to sacrifice for it.

At the core of this story is his combative relationship with his father, Doug Springsteen, whom he describes sitting night after night in the kitchen of their working-class household puffing on a cigarette and sucking down beers until he would unpredictably, but frequently, explode at the nearest target of his outrage, which often was his only son.

“My dad’s desire to engage with me almost always came after the nightly religious ritual of the ‘sacred six-pack,’” Springsteen writes. “One beer after another in the pitch dark of our kitchen. It was always then that he wanted to see me and it was always the same. A few moments of feigned parental concern for my well-being followed by the real deal: the hostility and raw anger toward his son, the only other man in the house. It was a shame,” Springsteen writes evenhandedly. “He loved me but he couldn’t stand me.”

The power in Springsteen’s book emerges from his steadfast refusal simply to create villains who embody the antagonistic forces he railed against as a youth — something every adolescent feels at one time or another. He transcends the bitterness that could have consumed him through an honest curiosity about the life forces that shaped his father, and a real wish not to let the sins of the father become those of the son.

Springsteen is chasing truth and understanding — not scapegoats.

With active, objective exploration as his guiding principle, Springsteen comes to the conclusion that “I haven’t been completely fair to my father in my songs, treating him as an archetype of the neglecting, domineering parent. It was an ‘East of Eden’ recasting of our relationship, a way of ‘universalizing’ my childhood experience. Our story is much more complicated. Not in the details of what happened, but in the ‘why’ of it all.”

Perhaps the most poignant moment, among many he shares, is their reconciliation, years after his father and mother, Adele, had quit New Jersey and started a new life across the country, with his younger sister, Pam, in San Mateo, Calif.

He recounts a visit from his father, who was increasingly battling various illnesses, yet still made the drive from the Bay Area to see his now-famous son in Los Angeles.

“Bruce, you’ve been very good to us,” the elder Springsteen tells his son, “and I wasn’t very good to you,” to which Bruce responds: “You did the best you could.”

“That was it,” Springsteen writes. “It was all I needed, all that was necessary.”

Although he reveals that much of this inner and outer-world analysis grew out of psychological counseling he underwent as an adult, the book also gives us a vivid picture of just how crucial music was as a life-renewing force for him.

“I began to feel the empowerment the instrument and my work were bringing me,” he says about wood-shedding his guitar chops. “I had a secret … there was something I could do, something I might be good at. I fell asleep at night with dreams of rock ’n’ roll glory in my head.”

Perhaps it’s the classic Catholic guilt at work, but Springsteen comes off admirably generous in recounting disagreements and outright betrayals that he’s been involved with along the way with family members, friends, bandmates, girlfriends (who remain largely unnamed), business associates, his first wife — actress Julianne Phillips — and his second — singer and songwriter Patti Scialfa, the mother of their three children.

He wisely avoides the descent into vitriol that sank Creedence Clearwater Revival front man John Fogerty’s autobiography “Fortune Son: My Life, My Music.”

Instead, he takes his rightful lumps for numerous transgressions, such as disbanding the venerated E Street Band in the late 1980s, after the peak of his massive popularity with the “Born in the U.S.A.” album. An inevitable process of an autobiography, of course, is that we get only his side of those disagreements, as equitable as he is in relating them.

He barely touches on the hurt he caused “The Big Man,” saxophonist Clarence Clemons, who freely expressed in his own interviews his pain at being told by “The Boss” that the E Street Band was being mothballed so he could explore other musical situations. His subsequent meditation on Clemons’ death in 2011 is a masterpiece of love and empathy.

Springsteen has an honest out for his frequent invocation of the better part of valor, noting toward the book’s end, “I haven’t told you ‘all’ about myself. Discretion and the feelings of others don’t allow it. But in a project like this, the writer has made one promise: to show the reader his mind. In these pages I’ve tried to do that.”

For the super faithful, he has supplied a wealth of insight into the creation of many of his greatest songs and albums. The relative lack of commentary on middling mid-career works such as “Lucky Town” and “Human Touch” likely tells us what we need to know about his thoughts on those.

He incorporates thoughts about his two sons, Evan and James, and daughter, Jessica, while wife Patti fulfills the role of near-saintly best friend, lover, muse and life partner, although it’s not hard to want to hear more about how those roles have fed, or derailed, her own musical ambitions, which are left for someone else’s book.

Structurally, “Born to Run” flows elegantly and effectively for the most part. One exception is his chapter about the family’s entrance into the world of high-end equestrian life because of daughter Jessica’s passion for horses. It feels awkward, almost trivial, coming immediately after his eloquently moving chapter about the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and his musical response to that world-jolting event.

A sage no less than Socrates famously observed, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” A more modern corollary also suggests that “The unlived life is not worth examining.”

Bruce Springsteen proves that he has taken on life fully engaged both in living and examining it, and in doing so, he’s delivered a story as profoundly inspiring as his best music.

No comments:

Post a Comment