The Champ and Mr. X

By James Rosen — February 20, 2016

http://www.nationalreview.com/

"Not many people,” Malcolm X told the writer George Plimpton in 1964, “know the quality of the mind he’s got in there.” The fiery minister for the Nation of Islam (NOI), head of its Harlem mosque and the sect’s most prominent spokesman, was talking about Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., the strikingly pretty and unrelentingly loquacious 22-year-old boxer from Louisville who was soon to dethrone Sonny Liston, thuggish and frightful, an 8-to-1 betting favorite, as heavyweight champion of the world.

For nearly four years, the period that witnessed Clay’s rise from light-heavyweight Olympic gold to heavyweight title, the public had known him as a benign clown, the Little Richard of sports. He fought in an unorthodox and rococo style, hands held low as he pranced around opponents; Clay’s chief preoccupation seemed to be to avoid blemish to my pretty face. Eschewing the Joe Louis model for black athletes, of quiet humility before white audiences, Clay proclaimed himself The Greatest, spouted amateurish poetry, tagged his opponents with derisive nicknames, and predicted, often accurately, the round in which he would dispense with them.

The sporting press had never seen anything like it. Yet even they overlooked the practical advantage the clown act derived from misdirection. Broadening the action beyond the ring lulled Clay’s opponents into complacency about his lethality inside it; focus on the Louisville Lip’s clowning obscured his speed of hand and foot, his gifts for spatial relations and evasion, his ability to take a punch. Only under such circumstances could members of the boxing press express surprise, when Liston and Clay finally met at ring center, that the challenger stood two inches taller than the champion.

In political terms, however, the act was harmless. Whenever sportswriters pitched him questions about the civil-rights movement, Clay cannily recoiled from controversy, steering the conversation back to his greatness, his prettiness, the big red Cadillac he would drive when he became champion; in this he showed the same agility, the same circular backpedaling, he had displayed on the streets of Louisville and when sparring for real.

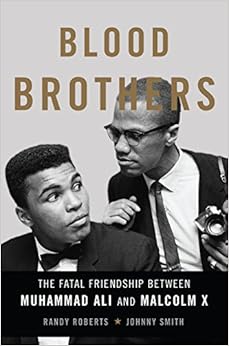

As Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith demonstrate in Blood Brothers, Clay’s use of misdirection advanced still another objective. Not until the last weeks before the Liston fight in February 1964, when Malcolm X — freshly excommunicated from the Nation of Islam by its vengeful leader, Elijah Muhammad — started showing up at Clay’s training camp, did the public, prodded by a newly aroused press, awaken to the boxer’s membership for the past two years in the NOI, the era’s most controversial religious sect.

Clay was dyslexic and a slow reader, but his mind was fiercely instinctual and finely calibrated: He knew rhyming boasts would boost ticket sales but talk of the Black Muslims would flatten them. So Clay effectively hid his association with the Nation until he had secured the goal he had harbored since the age of twelve: the heavyweight championship. Only then did he put his loquacity to work on behalf of his religious fervor — starting, as history records, with his change of name to Muhammad Ali. “Central to his life, relationships, and career,” the authors write, “was deception.”

Exhaustively researched and tautly written, Blood Brothers marks a milestone in the biographical literature of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, an invaluable addition to our understanding of America in the 1960s. In all it touches — the far-flung but interconnected worlds of race, religion, politics, sports, cities, organized crime, and the news media — this sober and detailed book, a dual biography that alternates between protagonists like a suspense novel, renders profound service. The authors unearth reams of new evidence, shine light on long-overlooked episodes, and hack away at the barnacles of mythology, thereby giving us the finest portrait yet of the doomed relationship that transformed Cassius Clay into Muhammad Ali.

History professors at Purdue and Georgia Tech, respectively, Roberts and Smith draw on an impressive array of sources: NOI telegrams contained in Malcolm X’s papers; FBI documents chronicling the Bureau’s surveillance of Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm; Louisville police records and declassified State Department files; the private papers of Ali’s previous biographers, stored in locations as distant as the University of Oregon; the business correspondence of the Louisville Sponsoring Group, Clay’s original management firm; the archives of the NAACP, deposited at the Library of Congress; the contemporaneous reporting of mainstream newspapers and magazines, as well as black outlets, including the Amsterdam News and Muhammad Speaks; obscure TV and radio broadcasts; congressional-hearing transcripts and court affidavits; and a handful of original interviews.

Flashing their power early on, the authors show in the introduction how the late Alex Haley, ghostwriter of the bestselling The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) and celebrated author of the 1976 novel Roots, a touchstone of American culture, misled Malcolm X — and subsequently the readers of the Autobiography — about an important matter. Tucked away in Haley’s papers at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture was evidence, in Haley’s own hand, that he withheld from Malcolm the fact that, while the new heavyweight champion intended to abide by Elijah Muhammad’s edict barring all NOI members from contact with the excommunicated Malcolm, Ali also told Haley that Malcolm was “still my brother, my friend.” Instead, Haley conveyed the opposite message, both to Malcolm and to subsequent readers, using a sterner quote from Ali that Haley represented as having come from his own interview with the champ, but that Haley had in fact lifted from a recent issue of Ebony. This misapprehension Malcolm took to his grave.

Haley manipulated Malcolm’s broken relationship with Ali in order to present a more sensational historical account. He selected and excluded events according to whether they fit into his agenda. In some cases, he tampered with the facts. But the truth was more complex than Haley let on.

This alone — the takedown of a major writer such as Haley — should guarantee Blood Brothers a wide audience, but there is much more that commends this transfixing book.

Armed with near-total comprehension of the daily whereabouts and activities of their two protagonists for a period of years, the authors chronicle in greater detail than ever before how Cassius Clay, elder son of a placid Baptist mother and a volatile Methodist father, gravitated to the self-help separatism of the Black Muslims; and how Malcolm Little, the career criminal who vaulted from a state penitentiary to the lieutenancy of Elijah Muhammad’s empire, slowly came to realize the unlimited potential that Clay, as both a boxer and a leader of black youth, held as an international ambassador for the NOI.

For Clay, the attraction germinated long before he met Malcolm: As early as October 1958, the FBI observed the 16-year-old Golden Gloves contender, on one of his earliest trips out of Louisville, conversing with NOI members outside their Atlanta mosque. The following year, a high-school teacher rebuked Clay for submitting an essay on the NOI, an early lesson in the need for him to conceal his affinity for the Black Muslims.

Witnesses to the Malcolm–Clay bond recognized it as unmistakably fraternal. Malcolm played the sage older brother, solemnly instructing Clay in NOI doctrines that only validated the rants that the Clay brothers, Cassius and Rudy, had grown up hearing about the evils of the white man from their father, Cassius Clay Sr. And Clay was the exuberant junior partner, bringing smiles to the face of the tightly wound minister as his daughters bounced on the boxer’s lap. “In general,” Malcolm told Haley, “I taught [Clay] that 90 percent of success would depend upon how alert and knowledgeable he became to the true natures and motives of all the people who flocked around him.”

By that measure, both men failed, for the arc of Ali’s whole career — his mismanaged finances, his susceptibility to those who encouraged him to fight long past when he should have stopped — testified to the champ’s woeful incapacity for discerning well-intentioned voices. As Ali’s longtime friend and photographer, Howard Bingham, told authorized biographer Thomas Hauser in Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (1991): “Ali still lets people take advantage of him and doesn’t always listen to the right people.”

Paramount among those who advised Ali with jaundiced motives — indeed, controlled him — was Elijah Muhammad himself. Born to a sharecropper–turned–Baptist preacher in 1897, the seventh of 13 children, Elijah Poole left school in rural Georgia by the fourth grade. He migrated to Detroit in the 1920s and there came under the tutelage of NOI founder Wallace D. Fard, an ex-convict and door-to-door salesman whose home-brewed Islamic theology blended sensible prescriptions for clean living and black pride with sci-fi beliefs about spaceships and evil scientists raising armies of white devils on remote islands. When Fard disappeared — amid charges he had ordered a human sacrifice — Elijah Muhammad, as Fard had renamed Poole, assumed leadership of the NOI and proclaimed himself the one true Messenger of Allah.

NOI membership nearly evaporated during the four years Muhammad spent in prison in the World War II era, following his conviction on charges of sedition and draft evasion, but by the mid 1950s some 50 NOI temples were operating in 22 states. Each contributed soldiers to the Fruit of Islam (FOI), the vanguard of security officers and enforcers who kept congregants in line by administering brutal beatings to renegade members. While the mainstream press portrayed the NOI as a hate group, citing its separatist rhetoric and vague talk of armed resistance, the reality was that it functioned more like a criminal syndicate, with revenues from temple dues, sales of Muhammad Speaks, and other compulsory enterprises keeping Elijah Muhammad in style while covering up his infidelities and punishing defectors.

Sports were of little interest to the Messenger, simply another manifestation of whites’ exploitation of blacks. When he learned that Jeremiah X, minister for the Atlanta mosque and chief recruiter in the Deep South, was cultivating a relationship with Cassius and Rudy Clay, both boxers, Elijah Muhammad reprimanded Jeremiah, reminding him to make converts, “not fool around with fighters.”

It so happened that the blossoming of the Malcolm X–Cassius Clay friendship, starting in early 1962, coincided with Clay’s swiftest period of ascent through the heavyweight ranks and with Elijah Muhammad’s rising displeasure with Malcolm’s penchant for publicity — which grew most acute after Malcolm, then the leader of Temple No. 7 in Harlem, greeted the assassination of President Kennedy with a statement describing it as “the chickens coming home to roost.”

Elijah also learned that Malcolm had become aware of the Messenger’s extramarital affairs and the children that those liaisons had produced; Elijah suspended Malcolm from the NOI before he could further probe those scandals. The sum total of these triangulated dynamics was that Elijah Muhammad discovered the value in having Cassius Clay around at more or less the same time he recognized the need to banish Malcolm X.

For a time, Malcolm and Clay ignored Muhammad’s edict forbidding their association and continued their daily rap sessions with reporters as Clay readied for Liston in Miami Beach. For Malcolm, it was a calculated gambit, an attempt at leveraging Clay’s celebrity to bolster his own standing within the NOI and perhaps to use the fighter as a human shield against FOI assassins. Here, as the Sixties came sharply into focus, Malcolm X — the shrewd tactician behind NOI’s expansion in the previous decade — miscalculated. In the authors’ words: “In a moment of weakness, he exploited his friendship with Clay, manipulating him and withholding the truth about his [own] future in the Nation. In a desperate attempt to prove his value to Elijah, he offered to deliver Clay to Chicago after the [Liston] fight, treating Cassius like some prize that could be bartered or traded. But Elijah did not have to buy Clay’s loyalty. He already owned it.”

Indeed, after capturing the title — at a time when he knew Malcolm X had been marked for death — Ali coldly turned his back. “Muhammad taught Malcolm X everything he knows,” the champ said in March 1964. “So I couldn’t go with the child, I go with the daddy.” Ali “understood the choice he had to make,” write Roberts and Smith: “And as he had so often before, he chose the less dangerous path. . . . Ali was not innocent. He had joined the chorus of violent ringleaders who raged about punishing Malcolm. . . . Without throwing a punch or raising his hand, Ali managed to hound the man he had once called his brother.”

“He’s just a boy,” Malcolm said of his ex-friend. “He doesn’t know what he’s doing. He’s being used.” Any chance at reconciliation ended, of course, with the assassination of Malcolm X — almost certainly on the orders, or in line with the wishes, of Elijah Muhammad — by a squad of FOI enforcers inside Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom in February 1965.

In time — specifically, in April 1969, when Ali’s conscientious objection to the Vietnam War had resulted in his being stripped of his title belt and license to box, and when, as the authors note, he “could not raise money or generate good publicity for the Nation” — he, too, fell prey to Elijah’s sanction and was suspended from the NOI. The nominal transgression was Ali’s statement to Howard Cosell, on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, that he would return to boxing if the money was right — a seeming contradiction of Ali’s original stand on religious principle. Unlike Malcolm X, however, Ali received an unspoken pardon and was permitted to rejoin NOI around the time his boxing career resumed.

Journalists who covered Ali for extended periods, as well as others who knew him well — or as well as a figure of so many faces and guises could be known — have attested to the manifest fear of the Black Muslims that guided the fighter’s actions for years to come. One example: In Sound and Fury: Two Powerful Lives, One Fateful Friendship (2006), the brilliant and nuanced portrait of the Ali–Cosell relationship by Dave Kindred, the Louisville Courier-Journal sportswriter whose residency aboard the Ali bandwagon dated back to 1966, the fighter was quoted as whispering to the reporter in November 1974, shortly after recapturing the heavyweight crown from George Foreman: “I would have gotten out of [the NOI] a long time ago. But you saw what they did to Malcolm X. I ain’t gonna end up like Malcolm X.”

This raises the chief problem with Blood Brothers, self-inflicted and wholly unnecessary in a book of such strength and value: namely, the pejorative claims its authors make vis-à-vis their predecessors on the subject of Malcolm and Ali, even as Roberts and Smith time and again acknowledge, in their main text and footnotes, their reliance on earlier writers and works. “Historians and biographers have misread the complicated relationship between them,” write Roberts and Smith. “Their respective biographers have neglected to show that Ali and Malcolm were much more important to each other than previously acknowledged.”

Not really. Did Manning Marable, whose 608-page Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (2011) was hailed as the definitive biography, fail to grasp the centrality of Ali in Malcolm’s life, or the elusiveness of the boxer’s psyche, when he wrote, “Few men would play such an outsized role in Malcolm’s life as this enigmatic, irrepressible figure”? Nor does Blood Brothers’ depiction of Ali’s being “exploited” by the NOI, of Elijah Muhammad’s privately disparaging his boxing ability, of Ali’s fearing the brutality of the NOI after Malcolm’s murder, differ so markedly from the accounts of Dave Kindred, quoted in Blood Brothers on the point, or of Mark Kram, the late Sports Illustrated writer and author of Ghosts of Manila: The Fateful Blood Feud between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier (2001):

Clay rushed toward the Muslims like an orphan, while the sect saw no utility in him, no gain, despite Malcolm X’s interest. . . . The Muslim hierarchy barely knew who Clay was, while the troops in Miami filled his head with dogma and privately laughed at the idea of Clay beating Liston. . . . [Malcolm X’s] murder would jolt Ali, drive home a point that he had given no thought; the Muslims played for keeps.

Roberts and Smith are hardly the first authors to overstate their analytic innovation; but Blood Brothers otherwise stands so tall as a testament to the value of real facts, of research and documentation, that the authors’ deviation from their own code, presumably for marketing purposes, appears all the more glaring.

Also, their ending feels rushed. While Ali’s regrets about his treatment of Malcolm X, articulated in a book of “reflections” he co-authored with his daughter in 2003, are duly recorded here, the disposition of the paternity lawsuits filed against Elijah Muhammad before his death, in February 1975, so central to Elijah’s split with Malcolm X, goes unreported. Similarly, very little space is devoted to Ali’s conversion, following Elijah’s death, to Sunni Islam, and none at all to his conversion, three decades later, to Sufi Islam.

And the authors make no attempt to connect Ali’s immersion in the NOI — which persisted to the end of his boxing career, with Elijah’s son Herbert Muhammad as Ali’s omnipotent manager — to the boxer’s ultimate fate: fighting too long, taking too many blows to the head, and having his mouth and movement, once his hallmarks, cruelly stilled by Parkinson’s syndrome. Are we to assume that Ali was receiving sound advice from Herbert Muhammad when the ex-champ, bloated at 38 and coming off a two-year layoff, signed to fight Larry Holmes? Was Ali at that point being driven solely by his own boredom and ego, or by financial straits worsened by the untold sums he had been compelled to fork over to the NOI? Here is the ultimate evidence that Malcolm X failed to instill in Ali a capacity for judging the motivations of those around him.

Ali’s doctors stress that his condition is one of motor function, not cognition. His brain functions as it always has; the Louisville Lip simply has no ability to verbalize his thoughts. Thus it is, sadly, as true today as in February 1964, when Malcolm X marveled at the singularity of his friend, that no one knows the quality of the mind Muhammad Ali has got in there.

– Mr. Rosen is the chief Washington correspondent of Fox News and the author of Cheney One on One: A Candid Conversation with America’s Most Controversial Statesman.

* National Review magazine content is typically available only to paid subscribers. Due to the immediacy of this article, it has been made available to you for free. To enjoy the full complement of exceptional National Review magazine content, sign up for a subscription today. A special discounted rate is available for you here.

No comments:

Post a Comment