Satan's Spokeman

By:

June 6, 2015

There’s a strange perfection to anti-Semitism. It fulfills the dream of complete explanation. Opens the way to absolute action. Unlocks the gates that bar ordinary people from the final madness of themselves. What more could you want from an intellectual drug? To the question of why history remains imperfect, it gives an answer: the Jews. To the question of why society is unsettled, it gives an answer: the Jews. To the question of why we personally have been kept from the power and acclaim we deserve, the Jews. The Jews. Always the damned Jews—the mystical cause of our unhappiness and unfulfillment. Anti-Semitism is an amphetamine, a barbiturate, and a hallucinogen, all in one.

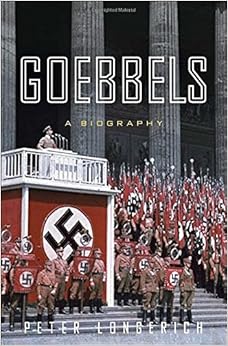

Which is why we should be terrified by the people toying again these days with the old tropes of Jew hatred and Jew suspicion: the pro-Palestinian protestors, the divest-from-Israel movement, the students at UCLA, Stanford, Temple. Whatever their initial motives, however innocent they claim to be, they are the pushers offering free tastes of an amazing, all-consuming drug to the weak, the frustrated, and the ambitious. And where the addiction leads—well, that’s the lesson in Peter Longerich’s recent book, Goebbels: A Biography.

Make no mistake: Longerich’s Goebbels is not a great book. The prose shuffles like an old man in carpet slippers. Except perhaps for the extent of Goebbels’s womanizing, the new revelations about Hitler’s minister of propaganda are too minor to interest the general readers who already know the man’s basic story, even while Longerich renders the Nazi’s days in eye-aching detail. The author is drawn to dated psychoanalytic accounts that seek in childhood the origins of his subject’s narcissism. Still, if I could, I’d attach a copy of the fat, ponderous volume to each of the new discoverers of anti-Semitism—chain it to their wrists so it banged and bruised them with every step—for the extraordinary lesson that Peter Longerich teaches about Joseph Goebbels is just how ordinary he was.

Ordinary in personality type, that is to say. You’ve met this kind of man. A failed intellectual, good enough to get his doctorate (which, at the German universities of the 1920s, was not nothing) but not good enough to find an academic post. An unsuccessful writer, good enough to complete a pair of plays but not good enough to have his work interest a producer. A lecher who excused and explained his lechery, to himself and others, with gauzy romanticism, even while every curve of a breast or flash of leg triggered his lubricious fantasies. A man with the minor deformity of a club-foot, convinced that he had been unfairly treated.

Goebbels was, in other words, a figure of some talent, in resentful need of an explanation for why (other than his own insufficiency) he had not been discovered as the greater talent he imagined himself to be. He was a man in need of Jew hatred, and from the time Adolf Hitler first seriously wooed him in 1926, until his suicide in Hitler’s bunker in 1945, Goebbels worshiped the leader who showed him the completeness of explanation that anti-Semitism provides.

The lesson could be learned from almost any of the central Nazis, those men in rings around Hitler. Behind Hannah Arendt’s often-attacked thesis of the “banality of evil” in Eichmann in Jerusalemstands at least this truth: The Nazis were not supermen. The evil they did was anything but banal, and they did their murderous work in anything but a banal way. But they started as rather ordinary types—people like the ones you could meet now, people like the students at UCLA, Stanford, and Temple today—who eventually felt licensed to become the monsters that one impulse of their personalities always urged them to be. Anti-Semitism was so addictive precisely because it seemed to set them free from the constrictions of normal human life.

In Goebbels’s case, as Longerich documents, we see a man, with a doctorate in literature, leading an official burning of un-German books as one of his ministry’s first actions in 1933. A government-led boycott of Jewish businesses quickly followed, and in the lack of meaningful opposition, Goebbels found himself free to be as monstrous as he liked.

And like it, he did. “Fight, fight is the cry of the creature. Nowhere is there peace, just murder, just killing, all for the sake of survival,” Goebbels wrote in the 30,000 pages of diary that Longerich has plowed through. “As it is with lions, so it is with human beings. We alone lack the courage to openly admit the way things are. In this respect wild animals are the better human beings.” The freedom was exhilarating: “A judgment is being carried out on the Jews that is barbaric but thoroughly deserved. … There must be no sentimentality in these matters,” he would later explain—and only Hitler’s Germany had found the unsentimental determination to do what must be done. “No other government and no other regime could produce the strength to solve this question.”

Joseph Goebbels Credit Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Born to a lower-middle-class Catholic family in the town of Rheydt in 1897, Goebbels was a sickly child, suffering from lung trouble and undergoing ineffective surgeries to correct his club-foot (a deformity that caused the German Army to reject his application during the First World War). A promising boy intellectually, first in his class at his Catholic school, his parents hoped he would enter the priesthood, but even before he began his university training, he was moving toward the views that would make him one of the most outspokenly anti-Christian of the senior Nazis.

After obtaining his doctorate in 1921, he was adrift—a twenty-four year-old living at home with no clear prospects and no clear direction. A little tutoring, some newspaper writing, and a bank-clerkship kept him going until 1924, when his interest in politics was awakened, in part by reading accounts of Hitler’s trial for the attempted coup of the Beer Hall Putsch. He joined the Nazi party and was hired by Gregor Strasser to help with a Nazi newspaper in Berlin.

Strasser’s socialism, shared by Goebbels, would prove a problem, which Hitler solved in 1926 by demanding personal loyalty, rather than adherence to a party platform, and by paying marked attention to Goebbels—who succumbed completely. “I love him,” Goebbels inscribed in his diary. “Such a sparkling mind can be my leader. I bow to the greater one, the political genius.”

A career of speech-making, arranging propaganda events, and successfully reorganizing the party’s chapter in Berlin was soon built, as the young man found at last an outlet for his previously unfocused energy and ambition. The violence of the local Nazis under his command, together with the anti-Semitic libels he printed in his newspaper, threatened him with legal troubles, but his election as a member of the Reichstag in the Nazis’ otherwise mostly unsuccessful 1928 campaign provided some immunity.

Determined to raise the party’s fortunes, he used the global economic crash of 1929 and the murder of a minor Nazi, Horst Wessel, by communists in 1930 as occasions for massive new propaganda campaigns. The elections of 1930 and 1932 showed pronounced support for the party—which Goebbels took as proof of the effectiveness of his work. But when Hitler was appointed Reich chancellor at the beginning of 1933, Goebbels was forced to wait a few months before joining the cabinet as propaganda minister. It was a delay at which he chaffed but one that only increased his personal dependence on Hitler’s approval.

From there on, Goebbels’s fingers were in everything: the Nuremberg rally, the Night of Long Knives, the takeover of all civil institutions, the censorship offices, the spreading of loudspeakers and cheap radios, the spectacle of the Olympics, Kristallnacht, the bold graphic designs of Nazi propaganda, the war fervor over the Sudetenland, the total-war strategy, the ministerial power struggles of 1943, and the last-ditch defense of Berlin. For all that, Goebbels was never granted full access to Hitler’s designs, and Longerich’s biography shows him constantly straining to catch up, concocting post-hoc propaganda to justify such events as the invasion of Poland, about which he had never been warned. Hitler may have liked Goebbels—he certainly cared for his six children and his wife, Magda, one of the few people around whom he could relax—but he never trusted Goebbels’s political sense or leadership talent.

What the Führer did trust was his anti-Semitism. As party gauleiter of Berlin, Goebbels prohibited Jews from using city services, and even after the army had become bogged down in its campaign against Russia, he raged against the presence of what he claimed were still 40,000 Jews in Berlin. The 1938 assassination of a German diplomat by a young Jewish man in Paris gave Goebbels the chance to organize supposedly spontaneous violence against the Jews across Germany. “As was to be expected,” he confided, “the entire nation is in uproar. This is one dead man who is costing the Jews dear.”

And on it went. When even Himmler wanted the destruction of the Jews kept quiet, Goebbels published a 1941 editorial announcing that “Jewry is now suffering the gradual process of annihilation which it intended for us.” He met with Hitler to insist that Berlin be the first city to have all its Jews deported to the concentration camps: “It would be best to kill them altogether,” he would explain. Even his anti-Christianity, showcased in the “immorality trials” he organized against the Catholic clergy and his closing of the Christian presses, was subsumed under his anti-Semitism. Christianity, he told his diary, “has crippled all that is noble in humanity”—because it is “a branch of the Jewish race.” Both religions “have no point of contact to the animal element, and thus, in the end they will be destroyed.”

What was destroyed, in the end, was Nazi Germany, and Longerich’s Goebbels describes in endless detail the last days in the Führer’s bunker where, once Hitler had committed suicide, Joseph and Magda Goebbels shot themselves after murdering their children by crushing cyanide capsules in their mouths. Along the way, six million Jews were systematically killed, while countless others lost their lives in the war. And it all begins with ambitious, resentful people playing with the drug of anti-Semitism to explain their religious, historical, social, and personal dissatisfactions.

“No Hitler, no Holocaust,” Milton Himmelfarb once famously insisted. It seems almost jejune to add “No anti-Semitism, no Nazis.” But the elements of the career laid out in Peter Longerich’s Goebbels: A Biography prove it true. This is why we must not allow toying with anti-Jewish tropes and symbols. This is why we must not indulge college protestors when they denounce the Jews. Just study the life of Joseph Goebbels—the spoilt priest, failed academic, and weak artist who found in the strange perfection of anti-Semitism everything he needed to will himself into evil.

No comments:

Post a Comment