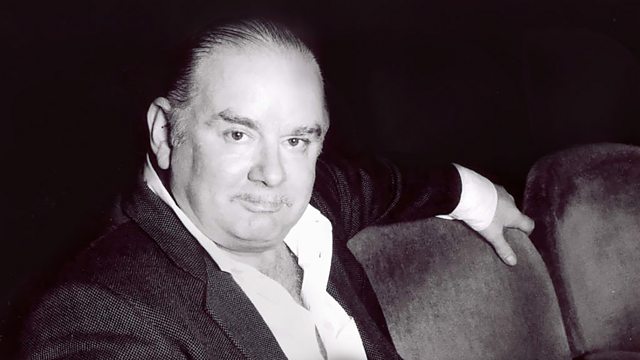

The biographer and novelist Peter Ackroyd once wrote we should tread carefully on the pavements of London for we are treading on skin, so how appropriate that his latest subject should be Charlie Chaplin.

4 April 2014

Ackroyd is made from London and so was Chaplin. The city was the comedian's inspiration, companion and ghost, his friend and enemy. Even when he was the most famous man in the world, he continued to be inspired by the city of his birth, but it also exerted a kind of fearful influence on him too. "I had a feeling of slight uneasiness," he once wrote, "that perhaps those streets of poverty still had the power to trap me in the quicksands of their hopelessness."

This is what Ackroyd loves writing about: what he calls the territorial imperative, the relationship between person and place, the idea that where you are born, where you live, or even the place you are running away from, will always influence you. It is flesh and concrete combined.

Ackroyd is the embodiment of the theory. As a child, he was taken on tours of London by his grandmother and, when he began to write, London was almost always his subject, directly or indirectly. He has written about the city itself in books such as London: A Biography (2000), Thames: Sacred River (2007) and London Under (2011) but he has also written many times about Londoners or what he calls the London visionaries: Blake, Turner, and Dickens. Writing about them is all part of the same process, he believes: every book is a chapter in a long book that will end on his death.

And Charlie Chaplin is the natural next chapter in that book, he says. Indeed, he sees Chaplin as being more or less the spiritual heir of Dickens and, in his new short biography of the comedian, compiles a long list of their similarities. He does it again for me when I call him at his home in London.

"There is a trajectory of the Cockney visionary," he says of Chaplin and Dickens. "Both seemed to share certain attributes - they were both let down by their mothers, they lived in poverty, they both had huge success at an early age, they were entranced by London's sensibility, all these elements came together. They are also linked by a common sensibility. Chaplin's film Modern Times is the cinematic equivalent of Dickens's Hard Times, so Chaplin carries on a strong tradition of social commentary and sensibility. I always think of Chaplin as being the heir of Dickens and continuing the Cockney tradition."

The negative qualities of Dickens and Chaplin are similar too, says Ackroyd. Both men always had to be in control, they could be dictatorial and domineering and could be invaded by sudden terrors and inexplicable fears - they were both extremely wealthy but feared their riches would be stripped away.

"Chaplin could be very imperious to those around him," says Ackroyd. "He treated his wives with scant regard, apart from the last one. He was perpetually angry at the world, and he vented his anger in terrible tantrums. He was dictatorial on the set and may not have been the nicest person unless he was trying to charm you or please you or entertain you." Or have sex with you? "He was very highly sexed and known for it throughout his Hollywood career - and he enjoyed the company of underage girls more than anybody else."

Ackroyd believes all this anger, frustration and bad behaviour derived from Chaplin's unhappy childhood. "He had a very unhappy childhood and he always thought the world was against him. He was put in an orphanage at the age of 10 or so; his mother was mad, or became mad; he did not know who his father was, and he drifted through the streets of South London when he was a kid."

Ackroyd describes those South London streets on the first page of the Chaplin book and he does it with the relish he always brings to descriptions of places. In the last decade of the 19th century, he says, the world of South London was frowsy, shabby, small and dirty; he lists the smells and sounds: vinegar, smoke, beer, leather and, over it all, the stink of poverty; but he also explains how this atmosphere became the source and centre of Chaplin's inspiration, just like it did 100 years before for Dickens and 100 years after for Ackroyd himself.

Ackroyd would much rather talk about Chaplin's connections to London than his own and at times the writer famous for his long, bright sentences becomes monosyllabic and dull when the conversation turns personal (he once said he does not find himself interesting). He does tell me a little about what he is working on and what makes up his day (words, words, words). In the mornings, he says, he is working on a biography of Alfred Hitchcock (the next of his Cockney visionaries); in the afternoons he is working on the third volume of his A History Of England, and in the evenings he is writing a novel (what it is about, he will not tell me, which is fair enough). All that writing from morning until night sounds obsessive, I say. "I'm not obsessed," he snaps. "Writing is my vocation, it is all I do."

Perhaps his obsession is London, then. He was born in 1949 and was brought up in Acton and when he was a child enjoyed touring the city with his family. In his Chaplin book, Ackroyd describes the great comedian's compulsion to return to his childhood homes so I ask Ackroyd if he has ever returned to his family home. He clams up again but answers reluctantly, "Yes, I have - it was strangely unfulfilling. It was smaller than I remember and not as interesting."

He says the sequences in the book describing Chaplin's returns to London were the ones he most enjoyed writing. "Chaplin loved going back. He seems to have found it to be the source and centre of his vision and imagination - he seemed to need to return to it in order to refresh his vision."

Is there something similar going on with Ackroyd? Possibly. He loves going on long walks through the city (and he would be doing it today were it not for the fact he has injured a tendon in his leg). "I still enjoy the act of walking around London - it is important to have that solid pavement beneath my feet and feel the enduring atmosphere as I go along. It has always been part of my appreciation and awareness of London, and the power of place is something that seems to play a large role in my life."

The research for the Chaplin book involved a few of those long walks but also a period of watching and rewatching every one of the surviving films and reading every one of the books on Chaplin (and the bibliography is massive). The obvious question is, why add another one to a subject that has been so thoroughly raked over, but I am glad Ackroyd has because not only does he bring his usual colour to a black and white world, he has a healthy, experienced scepticism for Chaplin's own autobiography - indeed, all autobiography.

"Chaplin's memoirs are not entirely accurate as far as I can see," he says. "He was a great liar and he would make up great chunks of life, but that is par for the course. There is nothing wrong with that. It may have become part of a narrative he believed himself and he was much affected by Dickens and Oliver Twist - he sort of became part fictional as well as part factual."

In the Chaplin book - as in all his books - Ackroyd is also willing to interpret and theorise as well as report, which also makes for some amusing and arresting sections. For instance, he suggests much of Chaplin's slapstick is homoerotic - indeed he goes further and suggests all popular comedy from the commedia dell-arte to contemporary pantomime is homoerotic. "The male bottom," he writes, "receives more attention than any other portion of the human anatomy in a succession of kicks and thrusts."

He does accept, though, that as much as he and many others love Chaplin, some people do not get him. "A lot of people don't find him funny at all. But his most endearing and funny films are the earliest ones - the Keystone ones, and the tiny shorts always showed Chaplin at his funniest and his best."

Ackroyd goes further than that and says Chaplin was not just a clown - he was a serious artist with the real Dickensian quality that was able to combine comedy and pathos, pity and pantomime. He also stands by one of the quotations in his book from another of the great silent stars, Fatty Arbuckle, who once said Chaplin would be the only one who would still be talked about in 100 years. Here we are 100 years later and, with one or two exceptions, he was right.

Charlie Chaplin is published by Chatto and Windus, £14.99

No comments:

Post a Comment