By Stephen H. Webb

May 6, 2014

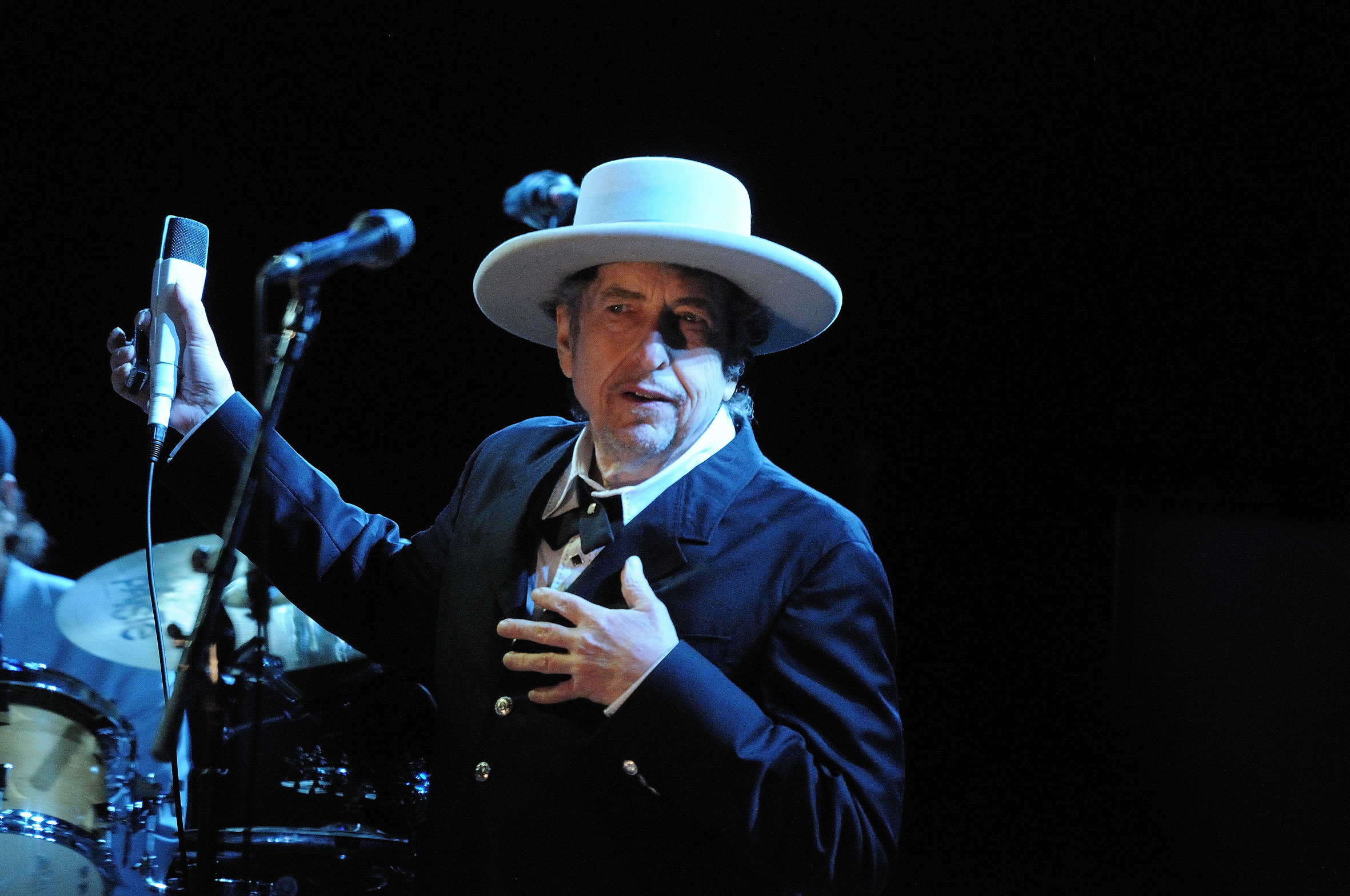

“Bob Dylan, Live: By Paolo Brillo”

Journalists have always been puzzled by Bob Dylan, but the confusion is of their own making. The pattern of treating him as a trickster whose words cannot be taken at face value was established in the sixties, when the rock intelligentsia wanted Dylan to be a political as well as musical revolutionary. He was neither, of course. His radicalness came from a deeply conservative understanding of musical history: He was reading Civil War era newspapers while everyone else was reading Norman O. Brown and listening to Gospel and Blues when music was becoming “pop” in the fifties. But the story of the sixties wasn’t complete without Dylan as its hero. His so-called followers couldn’t take no as an answer: His denials became obfuscations.

Of course, Dylan can be verbally perverse in interviews, but who can blame him when those who should know better seem clueless to what he is saying? Occasionally in these charades of misunderstanding, Dylan gets so frustrated that he spells everything out, revealing probably more than he intended. Such was the case in a Rolling Stone 2012 interview with Mikal Gilmore.

The interview begins to go wrong for Gilmore (and right for the rest of us) when he asks about “Rainy Day Women.” Dylan says that those who view it as a drug song “aren’t familiar with the Book of Acts.” This comment goes so far over Gilmore’s head that he can’t even respond to it.

Which shows he has no business interviewing Dylan, who has always been immersed in the Bible, its language and its theology. “Rainy Day Women” is more about persecution than intoxication. It sounds like a Salvation Army band playing a funeral march, but its words are deadly serious. When Dylan says that “they’ll stone ya when you’re trying to be so good” and that “they’ll stone ya when you’re tryin’ to go home,” he is speaking straight from the Bible. His comment about the Book of Acts makes the reference more explicit: it’s not just any good man being stoned, but Stephen.

Stoning, of course, was an ancient form of execution, and executions often take on a festive atmosphere. The carnival sound is thus quite appropriate to a song that reenacts an act of scapegoating. Hardly any Dylan fan hears the ritualistic and religious aspects of the song, but that says more about his fans than Dylan himself.

Read the rest of the article:

Stephen H. Webb is a columnist for First Things. He is the author most recently of Mormon Christianity. His book on Bob Dylan is Dylan Redeemed.

No comments:

Post a Comment