Every once in a while a great, conflicted country gets an insoluble problem exactly right. Such is the Supreme Court’s ruling this week on affirmative action. It upheld a Michigan referendum prohibiting the state from discriminating either for or against any citizen on the basis of race.

The Schuette ruling is highly significant for two reasons: its lopsided majority of 6 to 2, including a crucial concurrence from liberal Justice Stephen Breyer, and, even more important, Breyer’s rationale. It couldn’t be simpler. “The Constitution foresees the ballot box, not the courts, as the normal instrument for resolving differences and debates about the merits of these programs.”

Finally. After 36 years since the Bakke case, years of endless pettifoggery — parsing exactly how many spoonfuls of racial discrimination are permitted in exactly which circumstance — the court has its epiphany: Let the people decide. Not our business. We will not ban affirmative action. But we will not impose it, as the Schuetteplaintiffs would have us do by ruling that no state is permitted to ban affirmative action.

The path to this happy place has been characteristically crooked. Eleven years ago, the court rejected an attempt to strike down affirmative action at the University of Michigan law school. The 2003 Grutterdecision, as I wrote at the time, was “incoherent, disingenuous, intellectually muddled and morally confused” — and exactly what the country needed.

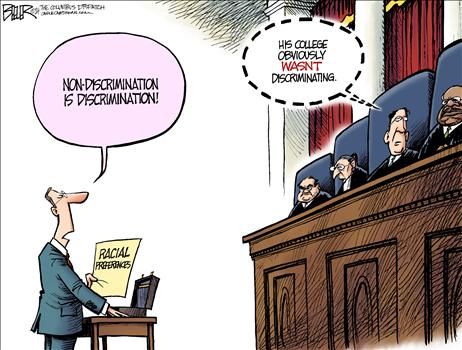

The reasoning was a mess because, given the very wording of the equal-protection clause (and of the Civil Rights Act), justifying any kind of racial preference requires absurd, often comical linguistic contortions. As Justice Antonin Scalia put it in his Schuette concurrence, even the question is absurd: “Does the Equal Protection Clause . . . forbid what its text plainly requires?” (i.e., colorblindness).

Indeed, over these four decades, how was“equal protection” transformed into a mandate for race discrimination? By morphing affirmative action into diversity and declaring diversity a state purpose important enough to justify racial preferences.

This is pretty weak gruel when compared with the social harm inherent in discriminating by race: exacerbating group antagonisms, stigmatizing minority achievement and, as documented by Thomas Sowell, Stuart Taylor and many others, needlessly and tragically damaging promising minority students by turning them disproportionately into failures at institutions for which they are unprepared.

So why did I celebrate the hopelessly muddled Grutter decision, which left affirmative action standing?

Because much as I believe the harm of affirmative action outweighs the good, the courts are not the place to decide the question. At its core, affirmative action is an attempt — noble but terribly flawed, in my view — at racial restitution. The issue is too neuralgic, the history too troubled, the ramifications too deep to be decided on high by nine robes. As with all great national questions, the only path to an enduring, legitimate resolution is by the democratic process.

That was the lesson of Roe v. Wade. It created a great societal rupture because, as Ruth Bader Ginsburg once explained, it “halted a political process that was moving in a reform direction and thereby, I believe, prolonged divisiveness and deferred stable settlement of the [abortion] issue.” It is never a good idea to take these profound political questions out of the political arena. (Regrettably, Ginsberg supported the dissent in Schuette, which would have done exactly that to affirmative action, recapitulating Roe.)

Which is why the 2003 Grutter decision was right. Asked to abolish affirmative action — and thus remove it from the democratic process — the court said no.

The implication? The people should decide.

The people responded accordingly. Three years later, they crafted a referendum to abolish race consciousness in government action. It passed overwhelmingly, 58 percent to 42 percent.

Schuette completes the circle by respecting the constitutionality of that democratic decision. As Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in the controlling opinion: “This case is not about how the debate about racial preferences should be resolved. It is about who may resolve it.”

And as Breyer wrote: “The Constitution permits, though it does not require . . . race-conscious programs.” Liberal as he is, Breyer could not accept the radical proposition of theSchuette plaintiffs that the Constitution demands — and cannot countenance a democratically voted abolition of — racial preferences.

This gives us, finally, the basis for a new national consensus. Two-thirds of the court has just said to the nation: For those of you who wish to continue to judge by race, we’ll keep making jesuitical distinctions to keep the discrimination from getting too obvious or outrageous. If, however, you wish to be rid of this baleful legacy and banish race preferences once and for all, do what Michigan did. You have our blessing.

Read more from Charles Krauthammer’s archive, follow him on Twitter or subscribe to his updates on Facebook.

Read more on this topic:

No comments:

Post a Comment