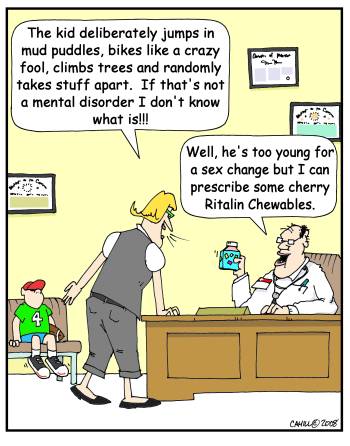

The allure of psychotropic drugs is about more than better grades for kids.

Almost 14 years ago, the inaugural issue of Policy Review under newly appointed editor Tod Lindberg ran an essay of mine called “Why Ritalin Rules.” It observed that American children were taking psychotropic drugs at (then-) record rates; that some doctors and other experts believed methylphenidate (the generic name for Ritalin) was being over-prescribed; that the disorder for which it and related stimulants were given — Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder — included a uniquely protean symptoms checklist; and that the line between science and advocacy was hard to find in the bustling pediatric zone of the psychotropic universe.

Alongside praise, the piece also drew flak — lots of it. Brickbats crossed the political aisle. From left to right, some readers hated it. At the time, that reaction seemed surprising. After all, unlike many pieces penned in those days about children and psychiatric drugs, “Why Ritalin Rules” rounded up some ten years’ worth of medical and other specialized literature. It wasn’t written to inflame, but to try and understand a potent and obvious development. Regardless, the conclusion drawn from all the emotional static was that the moment to have a reasonable conversation hadn’t yet arrived.

That was then. What a difference a decade-plus and millions more prescriptions can make.

Sunday, on the front and center of page one of the New York Times, author Alan Schwarz thoroughly if inadvertently ratifies the argument of “Why Ritalin Rules” in a long and absorbing story called “The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder: The Number of Diagnoses Soared Amid a 20-Year Drug Marketing Campaign.”

A few highlights from his report: Prescriptions for stimulant drugs such as Ritalin and Adderall have more than quadrupled in the past ten years. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control, “ADHD is now the second most frequent long-term diagnosis in children, narrowly trailing asthma.” Citing the same CDC, a psychologist and professor emeritus at Duke University named Dr. Keith Conners — for 50 years a leader in the effort to medicate children exhibiting the symptoms of ADHD — is emblematic of the specialists now having second thoughts. The rising rate of diagnosis, he recently told an assembly of fellow experts, is “a national disaster of dangerous proportions.”

Apparently, these are now legitimate subjects for discussion. In fact much of what Schwarz relays, like Dr. Conner’s quote, is more alarming than anything in my earlier Policy Review piece. The Times story also does something else done first in “Why Ritalin Rules”: It administers a standard “Could you have ADHD?” quiz to a number of subjects. Just as uncanny, it reaches the same results that appeared in my more limited experiment back in 1999. Some half of those canvassed by such a quiz, in 1999 and today, appeared likely to have ADD/ADHD, i.e., they would probably qualify for stimulant drugs.

“The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder” isn’t the only revisionist or probing look at psychotropic drugs since the explosion of the 1990s. In 2001, a cover story in Time magazine by Nancy Gibbs on “The Age of Ritalin” emphasized the social complexity of the medications. Other essays here and there have mapped related human ground. There’s also the fact that “prescription drug abuse continues to be the nation’s fastest growing drug problem,” as a 2013 report from the Drug Enforcement Administration puts it; about 1 million out of 6 million “nonmedical users,” it’s estimated (somehow) in that document, are users of stimulants. And the moral hazard assumed by college kids and others who sell their own pills to people who end up in emergency rooms has barely been touched.

All of which raises a question that might finally get a fair hearing now: Given these and other questions related to the prescription explosion, why do psychotropics still rule?

Some people who study drugs make the commonsensical point that every age has its chemical remedies of choice. And so one answer might be that just as Valium was the it-pill for mothers and doctors in an era when many women were at home with plenty of kids while their husbands were away working, so do today’s pediatric medications seem to help a different group of women: those who aren’t home all day, who are working outside the home, and who often don’t have husbands. A study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, for instance, found that divorce essentially doubles the likelihood that a given child will be prescribed stimulants.

And yet — to sound a note often missing that also demands a listen here — divorced and never-married households aren’t the only ones choking for air. Even moms who aren’t single are making similar frantic rounds: mother and wife and breadwinner, housekeeper and laundress, chef and volunteer, and the rest. They, too, have smaller margins for domestic error than they did before. So many women perceive, and frequently report.

Forget the debate about having it all. The ideological idol of “equality” has trickled down to mean that many women are expected to be doing it all. They’re feeling it. And the drug companies feel their pain. Consider this note from the Times piece: When federal guidelines changed in the late 1990s such that direct marketing became possible, writes Schwarz, “pharmaceutical companies began targeting perhaps the most impressionable consumers of all: parents, especially mothers.”

The widest lens on the pediatric psychotropic explosion may be this: It’s in part another consequence of the rotten deal that many women, single and married, have gotten out of the sexual revolution. Not all of them, obviously enough, but many. In ways that aren’t widely acknowledged yet, and someday will be, the “family changes” of the post-revolutionary world have stretched certain members of humanity to the breaking point — starting with, but not limited to, some children.

Thus, school under the new family regimen becomes longer than ever before (before- and after-care programs have exploded in tandem with stimulant use). Districts overburdened by their role as parent substitutes respond by reining in whatever they can (recess and exercise hours have been cut back in tandem with stimulant use). Legislatures all over consider shortening or abolishing summer vacation — because in an age without family backup, “vacation” is just an annual headache of more child-care bills.

And so goes the continuing and mostly unseen squeeze on childhood. Today’s kids are now institutionalized for more hours than their parents were, with less time to jump and run and move muscles and bones than their parents had. Many are also without fathers, as everyone knows. Is it any wonder that the advertising wizards have come up with the message that at least something will help Mommy out: taking your medicine?

“Better test scores at school, more chores done at home, an independence I try to encourage, a smile I can always count on,” as one ad reported in the Times had one Mommy say. In another ad for another drug, the caption ran, “There’s a great kid in there.” The child pictured was taking off his mask. Wearing a monster suit.

It’s not the whole story. But it’s not okay.

Many people thank God and their doctors for what performance-enhancing drugs have done for their own children and families. No one doubts it. But what’s gone missing from the discussion is this underlying reality: In an age when families from high to low are imploding, the pressure on everyone to toe the line is enormous — especially kids. The family that once protected children in all kinds of ways, including by adopting a more forgiving and less institutional standard for their behavior, is now weakened and defensive as never before. It leaves a vacuum that only institutions can fill — and they do, sometimes aided by drugs to help kids behave according to institutional demands. This aspect of the gravitational pull toward the psychotropic universe deserves to be part of the conversation, too, and mostly hasn’t been.

As Dr. Lawrence Diller — who was already voicing heretical thoughts about the stimulant explosion back when I quoted from his book Running on Ritalin in 1999 — now tells the Times, in a striking metaphor: “Pharma pushed as far as they could, but you can’t just blame the virus. You have to have a susceptible host for the epidemic to take hold. There’s something they know about us that they utilize and exploit.”

Exactly. And what Pharma knows better than most is that the happy talk about how kids today are doing fine, thank you very much, is a story we tell ourselves to avoid the obvious. Some of their moms aren’t all right, either, another fact that doesn’t get nearly the attention it should. And some of those fathers are suffering from the fallout too, whether self-inflicted or not. In the ashes of the sexual revolution, someone has found a gold mine.

— Mary Eberstadt is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and author most recently of Adam and Eve after the Pill and How the West Really Lost God.

No comments:

Post a Comment