By Jeff Jacoby

October 20, 2013

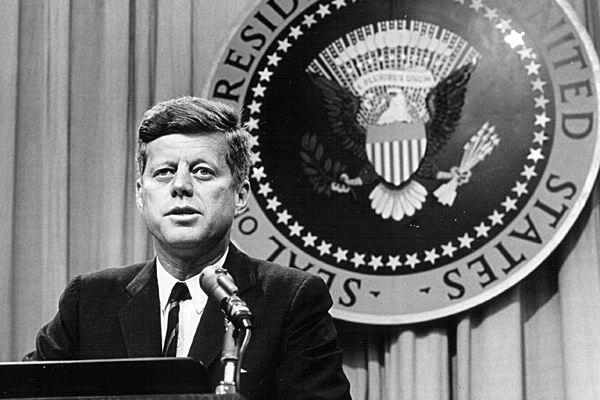

AS DEMOCRATS begin maneuvering for the 2016 presidential race, there isn’t one who would think of disparaging John F. Kennedy’s stature as a Democratic Party hero. Yet it’s a pretty safe bet that none would dream of running on Kennedy’s approach to government or embrace his political beliefs.

Today’s Democratic Party — the home of Barack Obama, John Kerry, and Al Gore — wouldn’t give the time of day to a candidate like JFK.

The 35th president was an ardent tax-cutter who championed across-the-board, top-to-bottom reductions in personal and corporate tax rates, slashed tariffs to promote free trade, and even spoke out against the “confiscatory” property taxes being levied in too many cities.

He was anything but a big-spending, welfare-state liberal. “I do not believe that Washington should do for the people what they can do for themselves through local and private effort,” Kennedy bluntly avowed during the 1960 campaign. One of his first acts as president was to institute a pay cut for top White House staffers, and that was only the start of his budgetary austerity. “To the surprise of many of his appointees,” longtime aide Ted Sorensen would later write, he “personally scrutinized every agency request with a cold eye and encouraged his budget director to say ‘no.’ ”

On the other hand, he was a Cold War anticommunist who aggressively increased military spending. He faulted his Republican predecessor for tailoring the nation’s military strategy to fit the budget, rather than the other way around. “We must refuse to accept a cheap, second-best defense,” JFK said during his run for the White House. He made good on that pledge, pushing defense spending to 50 percent of federal expenditures and 9 percent of GDP, both far higher than today’s levels. Speaking in Texas just hours before his death, he proudly took credit for building the US military into “a defense system second to none.”

Since that terrible day in Dallas 50 years ago, popular mythology has turned Kennedy into a liberal hero. Some of that mythmaking, as journalist and historian Ira Stoll argues in a new book, “JFK, Conservative,” was driven by Kennedy aides, such as Sorensen and Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who had always wanted their boss to be more left-leaning than he was. Some of it was fueled by the Democratic Party’s emotional connection to the memory of a martyred president, and its understandable desire to link their priorities to his legacy.

But Kennedy was no liberal. By any reasonable definition, he was a conservative — and not just by the standards of our era, but by those of his era as well.

Stoll draws on an embarrassment of riches to make his case.

When the young JFK launched his first political campaign for the US House in 1946, a profile in Look magazine homed in on his conservatism:

“When young, wealthy, and conservative John Fitzgerald Kennedy announced for Congress, many people wondered why,” it began. “Hardly a liberal even by his own standards, Kennedy is mainly concerned by what appears to him as the coming struggle between collectivism and capitalism. In speech after speech he charges his audience ‘to battle for the old ideas with the same enthusiasm that people have for new ideas.’ ”

He hadn’t changed his political stripes by the time he ran for the Senate in 1952, challenging incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. Stoll notes that Massachusetts newspapers wanting to back a liberal in that race came out for the Republican — the Berkshire Eagle, for example, endorsed Lodge as “an invaluable voice for liberalism.” When his reelection in 1958 made it clear that Kennedy would be running for the Democratic presidential nomination, Eleanor Roosevelt was asked in a TV interview whom she would support if forced to choose “between a conservative Democrat like Kennedy and a liberal Republican [like] Rockefeller.” FDR’s widow, then as now a progressive icon, answered that she would do all she could to make sure Kennedy wouldn’t be the party’s nominee.

Many on the left felt that way about JFK. When he decided to resume nuclear testing in 1962, Bertrand Russell attacked him as “much more wicked than Hitler,” and Linus Pauling, who would receive that year’s Nobel Peace Prize, predicted that he would “go down in history as . . . one of the greatest enemies of the human race.” Left-wing intellectuals raged against Kennedy’s failed attempt to topple Fidel Castro (the renowned sociologist C. Wright Mills said the administration had “returned us to barbarism”). Liberals within the administration expressed dismay for Kennedy’s unwavering support for tax cuts. Schlesinger called one of Kennedy’s exhortations “the worst speech the president had ever given.”

Nearly 30 years ago, an essay in Mother Jones magazine asked: “Would JFK Be a Hero Now?” If the answer wasn’t obvious then, it certainly is now. In today’s political environment, a candidate like JFK — a conservative champion of economic growth, tax cuts, limited government, peace through strength — plainly would be a hero. Whether he would be a Democrat is a different matter altogether.

No comments:

Post a Comment