The Heart of the Heartland

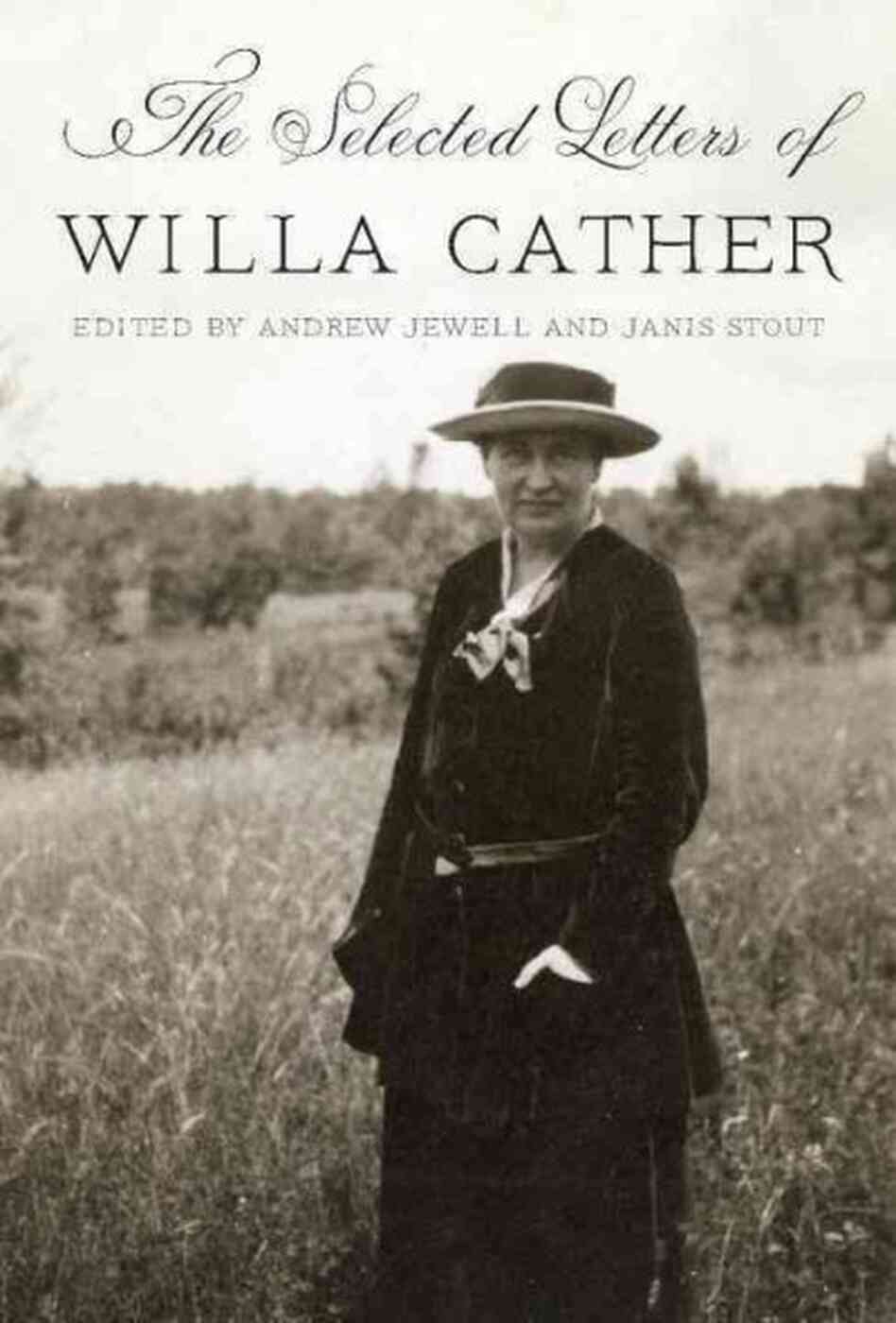

The Selected Letters of Willa CatherEdited by Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout(Knopf, 752 pages, $37.50)

Willa Cather’s literary reputation is even now, nearly 70 years after her death, less than clear. In her day—born in 1873, she published her main novels and books of stories between 1912 and 1940—she was regarded as insufficiently modernist, both in method and in outlook. She was later found to be a poor fit for academic feminism, for she wrote about the great dignity of female strength and resignation in the face of the harshest conditions. Advocates of gay literature who inhabit universities under the banner of Queer Theory have attempted to adopt her, taking her for a lesbian—she never married and had no serious romantic relationships with men—but her lesbianism remains suppositious at best. The powerful critics of her day and of ours have never lined up behind her. All she has had is readers who adore her novels and stories.

I am among them, and if pressed I should say that Willa Cather was the best novelist of the 20th century. Not all of her novels were successful: One of Ours, Lucy Gayheart, Sapphira and the Slave Girl don’t really come off. But those that do—O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), My Antonia (1918), A Lost Lady (1923) The Professor’s House (1925), Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), and Shadows on the Rock (1931)—do so with a grace and grandeur that show a mastery of the highest power.

Willa Cather’s great subject was immigration to America, chiefly among northern Europeans, their endurance in the face of nature’s pitiless hardships, and what she calls “the gorgeous drama with God.” Her prose was confidently cadenced and classically pure, never—like that of Hemingway or Faulkner—calling attention to itself, but instead devoted to illuminating her characters and their landscapes. (No one described landscape more beautifully than she.) Snobbery, egotism, politics never marred her storytelling. She wrote with a fine eye for the particular without ever losing sight of the larger scheme of the game of life.

Cather’s favorite of her own novels, Death Comes for the Archbishop, her account of two missionary French priests settling what will one day be New Mexico, strikes so exquisite a note of reverence that many people took its author for a Catholic. She wasn’t. Born a Baptist, she later became an Episcopalian. In one of the letters in the recently published collection The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, Cather writes to a sociologist at the University of Miami named Read Bain that she was not a Catholic nor had she any intention of becoming one. “On the other hand,” she wrote, “I do not regard the Roman Church merely as ‘artistic material.’ If the external form and ceremonial of that Church happens to be more beautiful than that of other churches, it certainly corresponds to some beautiful vision within. It is sacred, if for no other reason than that it is the faith that has been most loved by human creatures, and loved over the greatest stretch of centuries.”

THAT WE HAVE The Selected Letters of Willa Cather at all is a point of interest in itself. Willa Cather intensely disliked having her private life on display. She carefully promoted her books, frequently chiding publishers for their want of effort at publicizing them and stocking them in bookstores. But she didn’t think that promoting and publicizing extended to promoting and publicizing herself. She eschewed writing blurbs for the excellent reason that “sometimes the best possible friends write the worst possible books.” She gave few interviews, and when she wrote something about another person in a letter, she not uncommonly asked that her recipient keep it in confidence. Like Henry James, she burned many of the letters sent to her.

“We fully realize that in producing this book of selected letters,” write the editors of The Selected Letters, “we are defying Willa Cather’s stated preference that her letters remain hidden from the public eye.” Their justification is that now, 66 years after her death in 1947, with her artistic reputation secure, “these letters heighten our sense of her complex personality, provide insights into her methods and artistic choices as she worked, and reveal Cather herself to be a complicated, funny, brilliant, flinty, sensitive, sometimes confounding human being.” The letters, in their view, flesh out in a useful way the skeletal figure of the pure artist that Cather preferred to project.

Nothing in The Selected Letters touches directly on the vexed question of Willa Cather’s sexuality—on, that is, whether or not she was a lesbian. The reason is the paucity of the letters to the two women with whom Cather was closest during her adult life. The first was Isabelle McClung, in whose family’s house she lived while a journalist and high-school teacher in Pittsburgh. Isabelle later married a violinist named Jan Hambourg from a Jewish family of musicians, which was painful for Cather, who didn’t much care for him. When Isabelle died, in 1938, Cather felt it as a great subtraction. The second, Edith Lewis, with whom Cather shared apartments in New York and vacation homes in Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy and in Maine, worked in publishing and later as a copywriter. She assisted in innumerable ways, from proofreader to nurse during Cather’s many late-life ailments. Lewis survived Cather and wrote a rather anodyne memoir of her after her death.

Read more at:

Read more at:

1 comment:

Sir:

While I am pleased that you enjoyed this essay from the October 2013 issue of The American Spectator enough to reproduce it in full, I must ask that you remove it from your weblog. Reprinting the complete text of our articles hurts both our newsstand sales and our web traffic figures, which, in turns, affects our bottom line, making it harder for us to commission excellent articles such as this one.

Thanks very much for your understanding.

Cordially,

Matthew Walther

The American Spectator

Assistant Editor

w-a-l-t-h-e-r-m-AT-s-p-e-c-t-a-t-o-r-DOT-o-r-g

PS: Do feel free to quote from or respond to our articles in the future.

Post a Comment