By John Banville

http://www.theguardian.com/books

22 July 2011

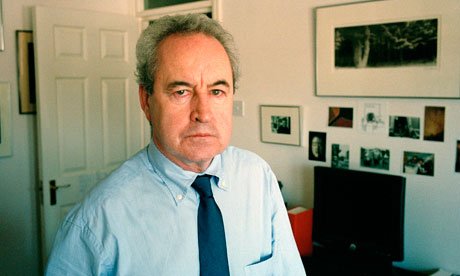

It takes two ... John Banville, aka Benjamin Black, at home in Dublin. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe

Certain moments remain in the mind with such force and clearness that one suspects they must be invented; that they are not held in the memory but generated out of the imagination. So vivid is my recollection of the birth of Benjamin Black that surely, I feel, a cunning artificer has been at work, fashioning a surreally realistic picture of something that happened quite differently from what I seem to remember. Consider that light falling on the sea, how effulgent and steady it is; consider the trees, improbably full-leafed for the time of year – and look at those birds! Has Madam Memory really such a piercing eye for detail, are her powers of recall so comprehensive?

This event took place on a day in early March of 2005. Someone once asked Iris Murdoch why she wrote so many novels and she replied ruefully that she believed each new one would exonerate her for the ones that had gone before. In the same spirit, I have never dared finish a novel without having a fresh one already on the go. I had completed The Sea in September 2004, and had been at work since the previous July on what would become The Infinities, and now, in the juvescence of the year, to quote Eliot's happily neologistic formula, came the tiger of inspiration, and suddenly I found myself veering off in a wholly unanticipated direction.

Well, no, not wholly unanticipated. My agent, Ed Victor, who likes to keep his clients not only happy but busy, had already suggested I might consider writing a crime novel. I did not tell him that in fact, many years ago, I did try my hand at a thriller, with embarrassing results which, I am glad to say, remain unpublished. The difference on this occasion was that I had a plot, characters and even dialogue ready-made. Early in the 2000s I had written, to commission, a television mini-series set in 1950s Ireland and America which, it had become clear, was not going to get made. This rankled, not only because I believed the thing had potential but because I hate wasted work.

March in Ireland can be a very lovely month, if you like your air rain-washed and your light wind-shaken. On the afternoon I am speaking of I was driving into Dublin along the sea road from Howth. There had been rain but it had stopped, and the light from a luminously clouded sky was pewter-bright, and puddles on the road were shivering in the wind, and the rooks above the trees in St Anne's Park were being tossed about the air like scraps of charred paper. I had reached a place along the road called Black Banks when Victor's prompting popped up again in my mind, and on the spot I knew what I would do: I would turn the television project into a novel. Not a John Banville novel, that was clear from the outset, but something altogether new to me: new, and venturesome, and risky.

The force of the idea was such that I drew the car to the side of the road and stopped and, for some reason, laughed. It was a loud laugh, unsteady, and sounded, even to my own ears, slightly maniacal. Thinking back now, I realise it was less a laugh than the birth-cry of my dark and twin brother Benjamin Black.

At once I wrote to my friend Beatrice von Rezzori, who runs a writers' foundation at Santa Maddalena, a wisteria-clad farmhouse in the hill country south-east of Florence where she and her late husband, the writer Gregor von Rezzori, had lived for most of their married life. Might I come and stay with her, to work on a project? Yes, she said, of course, she would give me a room in the tower – for of course the house has a 10th-century tower at the bottom of the garden. Thus it was that I found myself in the pink-tinged light of a cold March morning in Tuscany setting out, or, more prosaically, sitting down, to become someone else.

In another one of those suspiciously clear and definite memories I see myself there that Monday morning, in those medieval surroundings, at that scarred old olive-wood table, opening a blank, black-jacketed manuscript book and writing on the first page the title Christine Falls, while within me my heart quailed before the task I had set myself. The thing seemed asburd, a folly. Yet by noon, to my astonishment and some awe, I had written 1,500 words, more or less in the right order, a total it would have taken the poor drudge Banville a week to achieve, if he was lucky. Doctor Frankenstein himself can hardly have been more startled or more gratified when the lightning struck and his creature twitched into life. Suddenly, I had made myself other. A folly, yes: a folie à deux.

Of course, this sense of having, or being, a double identity was already familiar. Every novelist knows – perhaps everyone knows who has written even a letter, or a page of a diary – that the process of composition involves two separate sensibilities. The person who suffers and the mind that creates – Eliot again – occupy entirely different zones of action. When I stand up from my writing desk, "John Banville", or "Benjamin Black" – that is, the one whose name will appear on the title page – vanishes on the instant, since he only existed while the writing was being done.

The invention of an alter ego set me to thinking anew on this aspect of the writing life. In those March days, among the Tuscan hills, I mused much on the question of what it is to be a writer, and why I became one in the first place. Where, nearly half a century ago, did I imagine I was going, as I set out to forge – le mot juste! – a life in literature? Did I invent what I have become, or is imagination at its work again and do I invent now what I was then? Dizzying question.

Come, Benjamin, put your arm around me and we shall be comfortably one, mon semblable—mon frère!

No comments:

Post a Comment