A new biography gives the former prime minister her due.

July 23, 2013

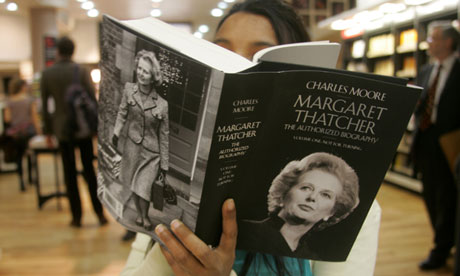

A reader leafs through Charles Moore's Margaret Thatcher – The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not for Turning. Photograph: Bimal Gautam/Barcroft Media

The first volume of Charles Moore’s authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher, covering her life up to Britain’s victory in the Falklands, is out just weeks after her death. It takes its place among the finest political biographies of all time.

Thatcher gave Moore full access to her papers and to all her friends and relatives, on condition that she never see the book. It was a wise precaution. Moore is a conservative, more traditionalist than Mrs. Thatcher (as he always calls her), and broadly sympathetic to her causes. But he was able to get frank responses from relatives, friends, and colleagues that might never have been forthcoming had they thought the book would be published in her lifetime.

Moore catches her in some lies and omissions. She had four boyfriends, a cache of letters to her sister showed, before she married the rich businessman Denis Thatcher. She always wanted to wear fetching clothes and have her hair done. The most important single fact about her, he says, is not that she was a conservative but that she was a woman, ready to use her charms as well as her intellect in dealing with men.

That’s not quite in sync with the common understanding of her in this country, particularly among conservatives, who saw Thatcher as the Iron Lady, fearlessly putting her ideas into effect, eschewing compromise, and never flinching from principle. Such an approach, Moore indicates, would have been doomed to failure and was usually not her way. Her ideas developed slowly and changed over time. She waited to fight for many of her great victories — over the coal miners and in privatizing government entities, subjects for volume two — until she had laid the groundwork and was fully prepared. Hers was a strategy of conviction tempered by prudence, compromise in pursuit of later success.

Consider her early parliamentary career, unfamiliar to American admirers. As education secretary, she acquiesced in the phasing out of the grammar schools, which had provided upward mobility to brainy lower-class children. She didn’t like the policy, but support was too strong. She ended up being cheered by the teachers’ union.

Nor was she an early opponent of the European Union (then called the Common Market). Like most centrist politicians of both major parties, she supported British entry. As a tourist I watched debate on the issue in the House of Commons in October 1971. West Country gentlemen with plummy pronunciation and Scots and North of England Labourites in incomprehensible regional accents spoke out against the Common Market. Thatcher may well have been in the hall, but I have no recollection of her speaking.

Four years later, after Edward Heath led the party to defeat, Thatcher was elected Conservative party leader. Most senior party leaders voted against her. In four years as leader of the opposition, Thatcher was a strong debater but not always a propagator of new ideas. Then Prime Minister James Callaghan made the miscalculation to delay the election until May 1979.

The 1979 Winter of Discontent — strikes by coal miners, public employees, garbage men, even gravediggers — turned voters away from Labour. The Conservatives ran a negative campaign, with the slogan “Labour isn’t working,” and won a solid majority.

As prime minister, Thatcher did not always spur her colleagues to go as far as she would have liked. She acquiesced in tax increases until she got a budget with deeper spending cuts in 1981. She started the process of privatizating public housing and privatized one public company by the time of the June 1982 Falklands victory. She stocked up on coal and gave the miners’ union a lavish settlement; confrontation would come later.

Argentina’s capture of the Falklands in April 1982 came as an unwelcome surprise at a time when the Conservatives were running third in polls, far behind the new Social Democrats, who were led by four former Labour ministers.

Moore shows how she made the decisions that led to victory. And contrary to American conservatives’ assumptions, she was angered at times by Ronald Reagan’s support of U.S. mediation efforts and by the pro-Argentina stance of Jeane Kirkpatrick.

Charles Moore leaves off with Thatcher speaking at a dinner of 120 all-male officials celebrating victory in the Falklands. Spouses were in another room. At the end she rose and said, “Gentlemen, shall we join the ladies?”

“It may well have been,” he writes, “the happiest moment of her life.”

— Michael Barone is senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner. © 2013 The Washington Examiner. Distributed by Creators.com

No comments:

Post a Comment