June 27, 2013

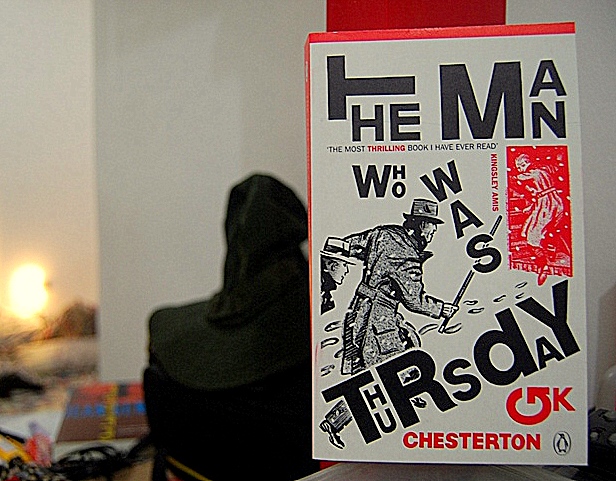

Thirty years ago, a British newspaper took an unscientific survey of current and former intelligence agents, asking them which fictional work best captured the realities of their profession. Would it be John Le Carré, Ian Fleming, Robert Ludlum? To the amazement of most readers, the book that won easily was G.K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, published in 1908.

This was so surprising because of the book's early date, but also its powerful mystical and Christian content: Chesterton subtitled it "a nightmare." But perhaps the choice was not so startling. Looking at the problems Western intelligence agencies confront fighting terrorism today, Chesterton's fantasy looks more relevant than ever, and more like a practical how-to guide.

Inevitably, my description has to give some spoilers, but they do not reveal any of the book's core revelations.

The book describes a Europe under threat from terrorists, from anarchists, dynamiters and assassins. To meet the threat, London's Metropolitan Police have formed an elite anti-anarchist squad, tasked to infiltrate the enemy. Following up a chance conversation, undercover detective Gabriel Syme attends a meeting of the General Council of the Anarchists of Europe, and is even elected to a vacancy in their leadership. This tight group has seven leaders, each of whom takes his codename from a day of the week. The mysterious overall boss is Sunday. Syme himself becomes Thursday.

Syme seems to have pulled off a major coup in the war against terror. But matters become more complicated, when he finds that he is not the only police infiltrator in the anarchist leadership. He discovers first another police spy, then another... could all the anarchist leaders really be detectives, or are all the detectives really anarchists? And who on earth is Sunday? Or is he not of this earth? As the detectives hunt the terrorists, and are themselves hunted, Chesterton creates a masterpiece of paranoia.

Chesterton himself was a bookish man with no real-world experience of police or intelligence. He did however have the dubious blessing of living in the first golden age of European terrorism, when issues of revolutionary subversion and counter-terrorism regularly filled the headlines. Since the 1880s, anarchist and revolutionary movements had carried out many violent acts across Europe and especially Russia, assassinating public figures and bombing trains and public meeting places. Scarcely less dangerous were nationalist and anti-imperial militants. Britain itself faced continuing threats from Irish and Indian activists.

Then as now, governments realized that the only way to defeat revolutionary terror was to penetrate and infiltrate the active groups, to gain intelligence about forthcoming attacks. Some agencies, though, carried this strategy to baroque extremes. The Russian secret police, the Okhrana, was notorious for the violence that it perpetrated itself in order to cast blame on revolutionaries, and also to establish the credentials of its own secret agents. When an agent infiltrated Russia's anarchist or Bolshevik underground, he naturally had to prove his credentials, to prove he was not a detective. And how better to do that than to carry out a vicious attack, by planting a bomb in a public place, even if that really did kill innocent civilians? Or imagine that police succeeded in converting and turning a terrorist to become one of their informants. If he was to remain in place to pass on priceless information, then naturally he had to be permitted to continue at least some violent acts, or his colleagues would immediately become suspicious.

Soon, even police agencies themselves had no idea whether a given attack was the work of real terrorists, or of agents and provocateurs notionally working for the regime. In this wilderness of mirrors, the only certain facts were provocation and deception. "Was anyone wearing a mask? Was anyone anything?" However fantastic The Man Who Was Thursday might appear, it was describing the stark realities of counter-subversion, with all their moral ambiguities. And that was what gave the book its appeal to latter day spooks.

Western intelligence agencies today operate under much stricter guidelines than their Russian Tsarist predecessors, but they still face similar dilemmas. Whether dealing with the IRA or Basque extremists, or today's Islamist militants, precisely the same issues recur. The only way to prevent terrorism is by gaining intelligence of what such groups are planning, before they launch attacks, and that means human intelligence. Despite recent advances in electronic surveillance, there is no substitute for either placing infiltrators in groups, or else winning over defectors. As the weary saying has it, "Everyone is an informant to somebody."

But it is not possible to run agents in those circumstances unless they are allowed to engage in at least some violent or criminal behavior. A host of European scandals in recent years have suggested the problems that result from such official tolerance. Sometimes, it seems as if the detectives really are all anarchists (or Islamists), and vice versa.

Just how far should agencies go to prevent terrorism? Chesterton's book includes another theme that agonizes today's security forces, namely the dilemma of knowing when radical thought and speech will translate into criminal action in the real world. A detective tells Syme of some radical innovations in counter-subversion: "The work of the philosophical policeman," he says, "is at once bolder and more subtle than that of the ordinary detective. ... The ordinary detective discovers from a ledger or a diary that a crime has been committed. We discover from a book of sonnets that a crime will be committed. We have to trace the origin of those dreadful thoughts that drive men on at last to intellectual fanaticism and intellectual crime."

We might rephrase the problem in modern terms. If a bomb has been planted or a soldier murdered in the streets, then police agencies have failed in their duty, and should have intervened earlier. But does that mean that they should arrest or try someone for thoughts and writings that might someday lead to committing such actions? Or at least, should they keep potential subversives under surveillance? We think of the futuristic police units in the film Minority Report, in constant pursuit of "Pre-Crime." It's a nasty, Orwelllian idea. But might it be an ugly necessity?

These are unsettling questions. Reading Chesterton's "nightmare" reminds us that they are anything but new.

No comments:

Post a Comment