Would shutting the detention camp satisfy them?

By Clifford D. May

May 2, 2013

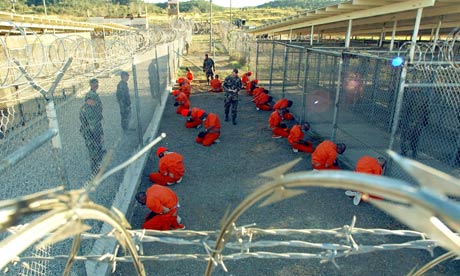

A photograph released on 11 January 2002 shows detainees accused of being Taliban and al-Qaida fighters in Guantánamo Bay prison. Photograph: Getty Images

The detention camp at Guantanamo Bay was established in 2002 to hold the most dangerous of those captured in what the Bush administration called the Global War on Terrorism. Controversy over the facility has simmered ever since. In recent days, it has begun to boil. One hundred detainees, at last count, are staging a hunger strike.

Their lawyers, along with self-proclaimed human-rights activists, are insisting that the U.S. respond by closing Guantanamo, something President Obama has long been eager to do. The questions seldom asked: How would that be accomplished? And what would it solve?

Closing Gitmo would, fairly obviously, require moving out those now detained. But where would they go? We could transfer them to prisons in the U.S., but is there anyone who seriously believes that once on American soil these detainees would become hearty eaters and happy campers?

More likely, having learned that refusing food brings concessions, they would use that strategy again and again. U.S. prison officials would respond as have U.S. military authorities at Gitmo: letting the prisoners protest by not eating (that’s their right), but not letting them die — instead, restraining them, if necessary, and administering the nutrition their bodies require. The not-so-nice term for that: force feeding.

In any case, the option of sending detainees from Gitmo to American prisons is moot for now because Congress, on a bipartisan basis, is adamantly opposed. Four years ago this month, the Senate voted 90 to 6 against spending the money necessary to close the facility in Guantanamo.

A second option: Let the detainees go. A little background may clarify why this, too, is not feasible. The Bush administration brought 779 prisoners to Guantanamo. By the time Obama became president there were 240 left — about two-thirds had been transferred to their home countries or to a third country willing to take responsibility for them. But in some cases, neither of those options was available because it is U.S. policy not to turn detainees over to regimes that might summarily execute or otherwise abuse them. (Remember the Uighur detainees who ended up in Bermuda because U.S. authorities would not send them to China?)

During Obama’s tenure in office, additional detainees have been shipped out. Of the 166 who remain, 46 are considered too dangerous to release or transfer. That leaves 86 detainees who have been “designated for transfer if security conditions can be met.” There has been confusion — and disingenuousness — about what that means. It does not imply that they are innocent. It does not even imply that U.S. authorities are convinced they no longer pose a threat. On the contrary, of those released from Gitmo to date, an estimated 27 percent have returned to terrorist activities.

Of the 86 “designated for transfer” about 50 come from Yemen. As the New York Times has reported, “Mr. Obama himself has indefinitely barred further repatriations [to Yemen] . . . because of Yemen’s active al Qaeda branch.” That branch, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, targets both Americans and the Yemeni government that we’re attempting to support. You’ll recall it was AQAP that gave us the Christmas 2009 “underwear” bomber.

Obama’s decision seems sensible to me but not to the Washington Post’s Max Fisher, who calls the situation “almost Kafkaesque in its cruel absurdity.” He asks if there isn’t something “distasteful and unsettling about imprisoning people not because they’ve done anything wrong but because they might in the future?” He does not appear to understand that he’s talking about members of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and affiliated groups apprehended on foreign fields of battle — not goat herders who were on their merry way to a cousin’s wedding in Afghanistan when they got caught up in the malevolent maw of the U.S. military.

In times of war, presidents have the authority to kill the enemy. In the past, those captured rather than killed were considered lucky. Those doing the capturing rather than the killing were considered humane. It makes no sense — legally, morally, logically — to say that an enemy whom the president can kill with a drone or a SEAL team suddenly undergoes a metamorphosis — speaking of Kafka — transforming into an innocent-until-proven-guilty suspect in a criminal investigation if he is handcuffed rather than buried. Never in the history of armed conflict have prisoners been given such a privilege.

And should our troops come to understand that anyone they capture rather than kill is likely to be pointing a gun at them again before long, they will be incentivized to use lethal force with increased frequency. Would that be preferable from a human-rights perspective? From an intelligence perspective? From any perspective?

Something else you should know: Since taking office, Obama has not sent a single al-Qaeda or Taliban member captured in Afghanistan to Guantanamo. Instead, those captured rather than killed in that country have been detained at a facility that was recently given over to Afghan authority. How do you think the living conditions in Afghan prisons compare to those at Gitmo?

Final point: When Max Fisher referred to Kafka, he was doubtless thinking of The Trial, the story of a man arrested by a shadowy authority that conceals the nature of his crime. But Kafka also wrote “The Hunger Artist,” about a performer who sits in a cage for weeks on end without eating. Eventually, the public loses interest in his “art,” and he dies unnoticed and unmourned. I’m not suggesting that should influence U.S. policy. I am suggesting that Fisher read it.

— Clifford D. May is president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a policy institute focusing on national security.

No comments:

Post a Comment