By TOM O'NEILL and DAN PIEPENBRING

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7145469/Did-Charles-Manson-unleash-murder-spree-Doris-Day-refused-make-rock-star.html

15 June 2019

Charles Manson

It was the crime that brought the Swinging Sixties to a savage halt.

On the night of August 8, 1969, a man and three women – Charles ‘Tex’ Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian – climbed into a beaten-up yellow Ford and headed towards Beverly Hills.

All four were part of a hippie commune about to become notorious the world over: the Manson Family.

Living in isolation outside Los Angeles, the group subscribed to a set of New Age rules – anti-establishment politics, drugs, free love, apocalyptic theology – laid down by their mesmeric leader Charles Manson, the man who had ordered them to make their fateful journey.

The four arrived at 10050 Cielo Drive, home of film director Roman Polanski and his wife, the actress Sharon Tate, about 40 minutes later.

Leaving Kasabian as a lookout, they approached the sprawling estate on foot.

Near the house they found 18-year-old Steven Parent, who had been visiting the caretaker at his home in the grounds. Watson shot Parent with a .22 Buntline revolver and he died instantly.

Inside the main house, the group swiftly hunted down its four occupants: Wojciech Frykowski, a 32-year-old Polish film-maker; his girlfriend, coffee heiress Abigail Folger, 25; Hollywood hairstylist Jay Sebring, 35; and Tate herself, who was eight months pregnant with Polanski’s child.

Her husband was in London scouting locations for his next film, but due to arrive home in time for the birth.

The horror of what happened next was unimaginable. Sebring was stabbed repeatedly and killed with two shots that pierced his lungs, while Frykowski was murdered with such savagery that the coroner recorded 51 stab wounds and 13 blows to the head.

Folger died while attempting to flee. Krenwinkel caught up with her in the garden and brought her knife down, stabbing her 28 times.

Tate was now the only one still alive, clad in her underwear and bound by the neck to Sebring’s dead body.

Watson ordered Atkins to kill her. Tate begged for her life to be spared, and that of her unborn child. ‘I want to have my baby,’ she said.

‘Woman, I have no mercy for you,’ Atkins responded. ‘You’re going to die.’

She stabbed her in the stomach. Watson joined in. Between them, the pair knifed her 16 times. As her life ebbed away, Tate cried out for her mother.

Atkins later told a cellmate that plunging the knife into Tate’s pregnant belly had been ‘like a sexual release’.

Atkins scrawled the word ‘Pig’ on the front door in Tate’s blood. Their work was done.

But it wasn’t over. The next night the same group convened with three additions: 18-year-old Steven Grogan, 19-year-old Leslie Van Houten and Charles Manson himself.

This time their victims were grocery store owner Leno LaBianca, 44, and his wife Rosemary, 38 – a couple unknown to them who lived next door to a house Manson had once visited in the Los Feliz neighbourhood of Los Angeles.

Manson chose Watson, Krenwinkel and Van Houten as his executioners and ordered them to go inside and kill everyone.

The trio burst in and stabbed Leno 26 times. Rosemary suffered 41 stab wounds. Before they left, the killers scrawled ‘Healter [sic] Skelter’ in blood on the refrigerator – misspelling the name of the Beatles song. On the walls they smeared ‘Rise’ and ‘Death to Pigs’ in Leno’s blood.

Manson and his cohort weren’t brought to justice for nearly four months. Only after they had been arrested on other charges, and Atkins had bragged to cellmates about her complicity in the Tate murders, did the case finally break open for Los Angeles police.

The sensational nine-month trial that followed saw Manson and his disciples sentenced to death – later commuted to life imprisonment – and made a celebrity of the prosecutor, Vince Bugliosi.

His subsequent book became a global bestseller and was widely accepted as the official version of the story.

But now, as the 50th anniversary of the killings approaches, I believe that much of what we accept as fact about that period is fiction – a conclusion I have reached after two decades of studying the case and speaking to the people who were there. I will reveal how:

- Doris Day’s refusal to release Manson’s music on her record label, laughing in the would-be rock star’s face, could have inspired the carnage at Cielo Drive, where her son used to live;

- Members of the Beach Boys pop group believed their phones were being monitored by the FBI over their connections with Manson;

- A Los Angeles deputy district attorney told me that some of the evidence I found was strong enough to overturn the verdicts against Manson and the Family;

- Fear about the murders is so strong in Hollywood that even decades on, A-listers refused to speak to me.

The horror of it all – a pregnant star slaughtered – unleashed something in the American psyche.

The subversive spirit of the 1960s had come on too quickly, and this, people thought, was the payback. Sales of burglar alarms and guard dogs soared. At the funerals of Tate and Sebring, actor Steve McQueen carried a pistol.

Tina Sinatra, Frank’s daughter, said her father had hired a security guard because of the attacks. ‘He was uniformed with a gun and he sat in the kitchen all night,’ she explained. ‘I can remember the whole tone of this city afterward. It defined fear.’

The trial began in July 1970. With his opening statement, Bugliosi made what was already a sensational case even more so. The motive he presented for the murders was spellbindingly bizarre.

His argument was that Manson, an avid Beatles fan, believed the group was speaking to him through their song lyrics. In Manson’s interpretation, black people would rise up against the white ‘Establishment’ and murder the entire race, apart from Manson and his followers, who would escape to a ‘bottomless pit’ – a concept from the Bible’s Book of Revelation.

Manson’s acolytes subscribed wholly to his vision of Armageddon, said Bugliosi.

By making it appear that the crimes against the white ‘Establishment’ – including the LaBiancas – had been committed by black militants, Manson, an avowed racist, had hoped to kickstart a race war. His followers were willing to kill to make it happen.

Bugliosi told the court the reason Polanski’s house had been chosen was that Manson had known the former tenant, Terry Melcher, a record producer and the son of Hollywood icon Doris Day.

Melcher had flirted with the idea of recording Manson, who had dreams of rock stardom, but decided against it.

In the spring before the murders, Manson had gone looking for Melcher at the house, hoping to change his mind. But a friend of the new tenants told him that Melcher had moved out. Manson didn’t like the guy’s brusque attitude.

For him, the house came to represent the ‘Establishment’ that had, he believed, rejected him. When he ordered the killings, he wanted to ‘instil fear in Melcher’, according to the testimony of Atkins.

This was a vital point. Manson didn’t go to the Polanski house on the night of the murders. To convict Manson of criminal conspiracy and get a death sentence, Bugliosi had to establish a compelling reason for picking that property. Melcher was that reason.

Melcher said in court that he’d met Manson three times, the last of which was around May 20, 1969, more than two months before the murders. After Manson’s arrest, Melcher became so frightened of the Family that Bugliosi had to give him a tranquilliser to relax him before he testified.

‘Ten, 15 years after the murders I’d speak to him and he was still convinced that the Manson Family was after him that night,’ Bugliosi later told me. But, as I was soon to find out, things were not quite as they seemed.

Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate, 1968

MY involvement in the case began in 1999 when I was asked by a film magazine to write a feature marking the 30th anniversary of the murders. It was the start of an obsession.

My first interviewee, photographer Julian Wasser, described the ‘great fear’ that descended on Los Angeles after the killings. In 1999 that fear appeared to be alive and well – at least among Hollywood’s A-list, many of whom declined to speak to me.

Warren Beatty and Jane Fonda said no. Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper, both reputedly close to Tate and Polanski: no, no. Candice Bergen, Terry Melcher’s girlfriend in 1969, said no too, as did Mia Farrow and Anjelica Huston.

Bruce Dern: no. Kirk Douglas: no. Paul Newman: no. Before long I began to wonder if there was a conspiracy of silence in Hollywood.

There was one major player, though, who agreed to talk to me: Vincent Bugliosi.

I asked if he could tell me anything about the case that had never been reported before. After a long silence, he told me to turn off my tape machine.

Bugliosi claimed that when he’d joined the case, police told him they’d recovered videotape from the loft at Cielo Drive. According to the detectives, the footage depicted Sharon Tate being forced to have sex with two unidentified men. He never saw the tape, so could not verify it.

Bugliosi claimed he told them: ‘Put it back where you found it. Roman has suffered enough. All it’s going to do is hurt her memory and hurt him.’

Armed with this information, I started pushing harder with my interviews.

As I won the confidence of some of Tate’s closest friends, they told me some concerning stories. The Sharon Tate they knew, warm and vivacious, was diminished in Polanski’s presence. She ‘just wasn’t herself when she was with him,’ said the German actress Elke Sommer. ‘She was in awe, or frightened; he had an awesome charisma.’

Maybe I was naive to think I could discover what had been going on at the Tate house. I decided to focus on one of the most perplexing figures in the case: Terry Melcher.

The story of Manson and Melcher starts with the Beach Boys’ drummer, Dennis Wilson. In the summer of 1968, when he was 23, Wilson split from his wife and moved into a lavish mansion to the West of Los Angeles.

One day, two hitchhikers, Ella Jo Bailey and Patricia Krenwinkel, caught his eye. He picked them up and took them back to his place.

The girls were members of the Family and told Manson about the encounter, and so began a summer of ceaseless partying for Wilson. Manson and his entourage moved in, with the girls cooking meals and sleeping with the men on command.

Manson advocated sex seven times a day: before and after all three meals and once in the middle of the night. In exchange for his women’s favours, Manson hoped to use his connection with Wilson to launch a musical career.

Rocker Neil Young remembered meeting him. ‘A lot of pretty well-known musicians around LA knew Manson,’ Young later said. ‘Though they’d probably deny it now.’

Among these was Melcher, a guest at one of Wilson’s marathon parties. Later that year, after Wilson grew tired of footing the bill – upwards of $100,000, including the cost of gonorrhoea treatments – Manson decided to hitch his wagon to Melcher’s star.

In the winter of 1968, he arranged for Melcher to come out to a house where the Family were staying in the San Fernando Valley, to hear his music. Manson prepared meticulously for the prospective meeting, but Melcher stood him up.

A second session was arranged, and this time, it went ahead. In May 1969, Melcher auditioned Manson in person, visiting the Spahn Ranch, a disused movie set where the Family now lived, twice over four days.

But something about Manson’s demeanour made Melcher decide against a deal. He never went back to the ranch or saw anyone from the Family again. Or so he would later say under oath.

In January 1969, Melcher and Candice Bergen left the house on Cielo Drive in the middle of the night, with no warning and four months left on the lease.

Still fascinated by the Beach Boys connection, I spoke to Dennis Wilson’s ex-wife Carole. I wondered, I told her, if Manson’s reach in Hollywood was further than had been previously known.

‘Yes, it sure was,’ she replied. She asked that I call her back the following Monday – we could meet for coffee.

When Monday came, though, she’d changed her mind. ‘I can’t talk to you,’ she said. There were a lot of people involved, she explained – too many. ‘It’s a scary thing,’ she added, ‘and anyone who knows anything will never talk.’

Meanwhile, I’d started to hear more about Melcher’s association with Manson. Bob April, a retired carpenter who’d been a fringe member of the Family, told me Manson ‘would supply girls’ for ‘executive parties’ that Melcher threw. But what would Manson get in return?

‘That’s why everyone got killed,’ April said. ‘He didn’t get what he wanted.’

Melcher, he suggested, had promised Manson a record deal ‘on Day Labels,’ his mother’s imprint. But Doris Day took one look at Manson ‘and laughed at him and said, “You’re out of your mind if you think I’m going to produce a f****** record for you.” Said it to Charlie’s face.’

Melcher and Manson ‘knew each other very well’, April said, adding: ‘I’ve tried to get this out for years.’

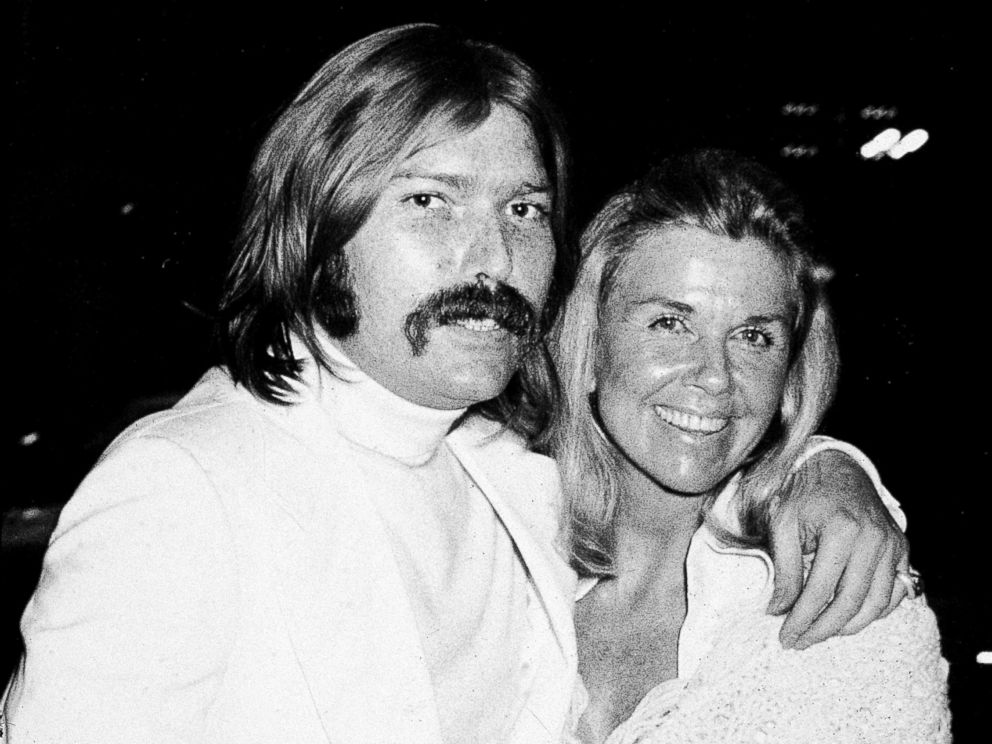

Terry Melcher and Doris Day

BY NOW, I had conducted hundreds of interviews. What I needed was documentary evidence. In the offices of the Los Angeles chief prosecutor, I found it.

A long yellow legal pad with scrawled notes in prosecutor Bugliosi’s handwriting. It was an interview with a biker named Danny DeCarlo, a key witness who had provided security for the Manson Family.

To my utter astonishment, in the crossed-out sections of Bugliosi’s notes, DeCarlo described three visits by Melcher to the Manson Family AFTER the murders, one in August, and two in September 1969.

At the grand jury hearing in December 1969, Bugliosi had asked Melcher whether he ever saw Manson after his May visits to the Spahn Ranch. ‘No, I didn’t,’ Melcher replied under oath. Three different times on the stand Melcher lied about not seeing Manson again.

This was a stunner, never before revealed. Clearly, this was information Bugliosi didn’t want before the jury. But why? He had argued that Manson chose the Cielo house to ‘instil fear’ in Melcher. But if Melcher had been with Manson after the murders, where was the fear?

In the archives of the LA county sheriff’s office, I found further proof that Melcher had visited Manson after the murders.

They had records of an interview with Paul Watkins, a key member of the Family who’d testified against Manson. He, too, saw Melcher at the Spahn Ranch, around the same time as DeCarlo had: the first week of September 1969.

What he told the unnamed interviewer was truly shocking: ‘Melcher was on acid. Was on his knees,’ he’d said. ‘Asked Manson to forgive him.’ Why did Melcher need Manson’s forgiveness?

There was yet another surprise in store. The Beach Boys’ surviving members had all declined to speak to me, but I spoke to John Parks, their former manager.

He recalled that Melcher had not only met Manson, but recorded his music, too. That was something else Melcher had expressly denied in court. Bugliosi repeated it in his closing statement: ‘He did not record Manson.’

After the murders, I asked, did Parks or any of his colleagues suspect Manson? Of course, he said. Everyone suspected Manson right away, even though it took the LAPD nearly four months to bring him to justice.

Parks went on to say something even more dizzying: he was positive that the FBI had sent agents to the Beach Boys’ office soon after the murders. ‘They were monitoring our phones, because they thought there was some connection with those guys,’ he said.

Parks told the FBI about Manson ‘early on’, but they didn’t seem to act on his tip. ‘I didn’t know why they weren’t doing anything,’ he said.

I spoke to Melcher in July 2000, our first meeting. He adamantly denied the idea that he’d been to the Spahn Ranch more than the times he’d testified to at trial. ‘You know I like you,’ he said. ‘If I didn’t like you, I’d take your briefcase and throw it off the balcony.’

I never saw nor spoke to Melcher again. He died in 2004, aged 62, of cancer, and with him went any possibility of learning so much more about the Family.

A year after Melcher’s death I showed Stephen Kay, co-prosecutor on the case, the notes I’d found in Bugliosi’s handwriting.

‘I am shocked,’ he said. ‘This throws a different light on everything. If Vince was covering this stuff up… if he changed this, what else did he change?’

I asked Kay whether this evidence would be enough to overturn the verdicts against Manson and the Family. Yes, he conceded. It could get them new trials.

Just like the omissions about the tape from the Polanski house loft, did Bugliosi change the story to protect Melcher, the child of one of Hollywood’s most beloved stars? Had he streamlined certain elements to get an easy conviction?

Or was this part of a broader pattern of deception, of bending the facts to support a narrative that was otherwise too shaky to stand?

Parks went on to say something even more dizzying: he was positive that the FBI had sent agents to the Beach Boys’ office soon after the murders. ‘They were monitoring our phones, because they thought there was some connection with those guys,’ he said.

Parks told the FBI about Manson ‘early on’, but they didn’t seem to act on his tip. ‘I didn’t know why they weren’t doing anything,’ he said.

I spoke to Melcher in July 2000, our first meeting. He adamantly denied the idea that he’d been to the Spahn Ranch more than the times he’d testified to at trial. ‘You know I like you,’ he said. ‘If I didn’t like you, I’d take your briefcase and throw it off the balcony.’

I never saw nor spoke to Melcher again. He died in 2004, aged 62, of cancer, and with him went any possibility of learning so much more about the Family.

Vincent Bugliosi during the Manson trial

A year after Melcher’s death I showed Stephen Kay, co-prosecutor on the case, the notes I’d found in Bugliosi’s handwriting.

‘I am shocked,’ he said. ‘This throws a different light on everything. If Vince was covering this stuff up… if he changed this, what else did he change?’

I asked Kay whether this evidence would be enough to overturn the verdicts against Manson and the Family. Yes, he conceded. It could get them new trials.

Just like the omissions about the tape from the Polanski house loft, did Bugliosi change the story to protect Melcher, the child of one of Hollywood’s most beloved stars? Had he streamlined certain elements to get an easy conviction?

Or was this part of a broader pattern of deception, of bending the facts to support a narrative that was otherwise too shaky to stand?

I wasn’t on some crusade to prove Manson innocent, or to impugn Bugliosi’s name. I just wanted to find out what really happened. Part of me was convinced that, if I kept pushing, I could crack this case and figure it all out. The other part of me feared that I was too late. Powerful interests had aligned themselves against the truth.

Over the years I have been warned off my researches many times. An interviewee implored me: ‘Don’t write this stuff. You’ll get killed.’ That was a warning I’d hear a lot from various parties.

Many of the people involved in this case are now dead. Bugliosi died in 2015, Manson in 2017. And yet the case continues to fascinate and horrify.

California’s current governor, Gavin Newsom, summed it up when he refused a third request for parole for Leslie Van Houten, now 69, just days ago.

‘I am concerned about her potential for future violence,’ he wrote on June 3, adding: ‘The gruesome crimes perpetuated by Ms Van Houten and other Manson Family members in an attempt to incite social chaos continue to inspire fear to this day.’

No comments:

Post a Comment