By Ben Sisario

http://www.nytimes.com/

November 11, 2016

Shortly before he died, Johnny Cash scrawled down eight short lines in a shaky hand, mortality clearly on his mind.

“You tell me that I must perish/Like the flowers that I cherish,” he wrote. He considered the hell of “nothing remaining of my name,” before concluding with an affirmation of his own legacy:

But the trees that I planted

Still are young

The songs I sang

Will still be sung

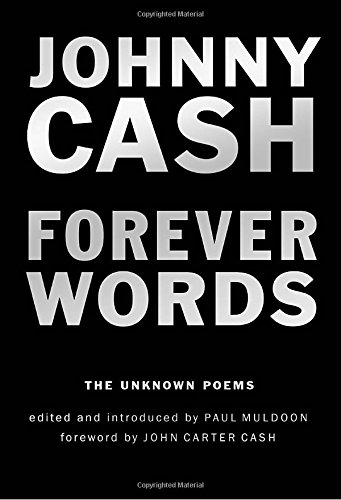

That poem, “Forever,” is part of a new collection, “Forever Words: The Unknown Poems” (Blue Rider Press), to be published next week. Edited by Paul Muldoon, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and Princeton professor, the book includes 41 works from throughout Cash’s life — the earliest piece, “The Things We’re Frightened At,” was done when he was 12 — that were among the papers left behind when Cash died in September 2003.

In some ways the poems mirror Cash’s songwriting, with terse ballads of outsiders in love, and parables drawn from the Bible; Cash’s version of Job is a wealthy cattleman who “cried out in agony/When he lost his children and his property.” And for Cash, who in his last years drew a new audience with a set of stark and fragile recordings, the poems present yet another look at a legend of American music.

“I want people to have a deeper understanding of my father than just the iconic, cool man in black,” said John Carter Cash, his son. “I think this book will help provide that.”

Some poems in “Forever Words” are unmistakably personal. “You Never Knew My Mind,” from 1967, captures Cash’s bitterness as he was going through his divorce from Vivian Liberto. (He married June Carter the next year.) “Don’t Make a Movie About Me” rejects the Hollywood machine but then slyly gives advice on a film treatment. “Going, Going, Gone,” from 1990, is a painfully detailed catalog of the ravages of drug abuse: “Liquid, tablet, capsule, powder/Fumes and smoke and vapor/The payoff is the same in the end.”

At other times, Cash seems to tinker with his own body of work. “Don’t Take Your Gun to Town,” dated to the 1980s, rewrites his classic 1958 song “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town,” in which a headstrong young cowboy dies when he ignores his mother’s advice. In the new version, a jaded man plans a “Taxi Driver”-like rampage against “people/Who need silencing,” but this time he listens.

“I believe he wanted to make a statement,” the younger Mr. Cash said. “He owned guns. But he definitely believed that you do not need to carry a gun in your pocket to town.”

Even so, Cash kept that version private, although, along with a handful of the poems in this collection, the manuscript for “Don’t Take Your Gun” was sold at auction.

In his introduction, Mr. Muldoon places Cash in a poetic tradition that comes out of Scotch ballads, and also raises a point that was hotly debated after Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature last month: Are song lyrics really the same as poetry? Do lyrics lose something when removed from their musical context?

Like Cash’s lyrics, the poems in “Forever Words” are written in plain language, usually with a clear rhyming meter. There are strikingly evocative images (“The dogs are in the woods/And the huntin’s lookin’ good”), as well as some well-worn phrases about soaring eagles and hell’s fury that might pass unnoticed in a song but jump out on the page.

In an interview, Mr. Muldoon put Cash alongside Leonard Cohen, who died on Monday, and Paul Simon as examples of songwriters whose words hold up on their own. Even so, he added, the “pressure per square inch” on lyrics “can be a wee bit lower than in a conventional poem.”

“But that’s not necessarily a bad thing,” he continued. There are occasions when the simple, direct phrase is the one that works.”

Taken together, Mr. Muldoon said, Cash’s poems have a broad sweep.

“You still see the same scenes — love, death, loss, joy, sadness,” Mr. Muldoon said. “The great themes of popular songs, and, indeed, poetry, which we welcome hearing about and making sense of as we go through our lives.”

The poems in “Forever Words” were chosen from about 200 pieces left by Cash in varying states of completion. Some may have been intended as lyrics, his son said, but it was not always clear. His father’s papers, Mr. Cash said, included biblical studies and even a dog-eared copy of Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

“They weren’t hoarders,” Mr. Cash said of his parents, “but they really didn’t like to throw things away.”

The Cash estate has released a number of posthumous albums, including “Personal File,” in 2006, a collection of intimate home recordings. A couple of years ago, Mr. Cash said, he was considering new projects with Steve Berkowitz, a producer and record executive who has worked extensively with the estate, and they began sifting through the poems.

Looking to recruit Mr. Muldoon as editor, Mr. Berkowitz said he met him for an “all-Irish breakfast” at an Upper East Side diner and read him excerpts from the poems without revealing the author.

“‘This is pretty strong stuff,’” Mr. Berkowitz recalled Mr. Muldoon’s saying. “‘Who is it?’ I told him, ‘This is Johnny Cash.’” (In an email, Mr. Muldoon said he did not remember the meeting, “which is not to say it didn’t happen.”)

The Cash estate is already at work on an album of songs based on the poems, with musicians including Kris Kristofferson, Jewel, Chris Cornell and Jamey Johnson, in a project similar to Billy Bragg and Wilco’s work with Woody Guthrie lyrics. The album is planned for release next fall.

Over the last year, the Cash estate has brought on a new management and marketing team, and the album is one of many new projects. Also planned are a Broadway show and a Johnny Cash slot machine, and the trust recently registered trademarks for phrases like “What would Johnny Cash do?” to place on clothing memorabilia.

When asked about these plans, Mr. Cash said that he and the managers of the trust — of which he is a beneficiary — strove to avoid crass commercialization, and also wanted to follow his father’s wishes.

“We try to live by the moral guide that he laid down,” Mr. Cash said, which, among other things, means no alcohol or tobacco ads. “But he also did Taco Bell commercials.”

The goal of “Forever Words,” Mr. Cash said, was to establish his father as a major poet and a “cultural American literary figure.”

There is also a personal benefit.

“When I read these things, it puts me back in touch with the man,” he said. “It lets me communicate with my father again.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/12/books/johnny-cash-the-poet-in-black.html