Victor Davis Hanson sees in the president shades of Achilles and Ajax. And maybe that's just what the country needs.

By

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/a-classicist-makes-the-case-for-trump-victor-davis-hanson/

March 7, 2019

Victor Davis Hanson is a senior fellow in military history at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and professor emeritus of classics at California State University, Fresno. The author of more than two dozen well-received books on topics ranging from the ancient world to the modern, Hanson lives in Selma, California, on a working farm that has been in his family for five generations. It’s an experience that’s given him strong views on subjects like illegal immigration, which has touched his life directly.

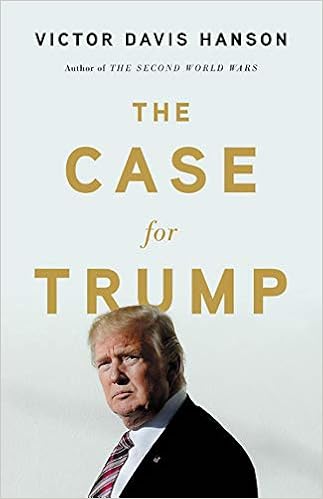

He opens his latest volume, The Case for Trump, in the year 2015, when Democratic and Republican strategists believed the country was becoming less industrialized and more digital, that new demographics—encouraged by open-border immigration proponents—would produce waves of new voters, and that the number of red-state voters was shrinking significantly. That meant gearing successful political pitches to the new political realities—globalism, open borders, identity politics, and other “woke” concerns. Then Donald Trump came down the escalator in his eponymous building, gave “the strangest presidential candidate’s announcement speech in memory,” and made “ready for the beginning of a nonending war with the press and civil strife within his party. He postured like Caesar easily crossing the forbidden Rubicon and forcing an end to the old politics as usual.”

Trump would play, Hanson writes, “an ancient role of the crude, would-be savior who scares even those who would invite him in to solve intractable problems that their own elite leadership could not. Trump was not that much different from the off-putting tragic hero—from Homer’s Achilles and Sophocles’s Ajax to modern cinema’s Wild Bunch and Dirty Harry.” In this crisply written and forceful analysis, Hanson argues that Trump has met those intractable problems head-on, shaking an establishment running on empty to its core, and, during his first two years, establishing an unparalleled record of solid presidential accomplishment.

Hanson takes us through the campaign again, commenting on how effectively Trump beat his primary opponents—11 well-qualified Republicans—and then Hillary Clinton with her billion-dollar war chest and most of the pollsters, establishment, academy, and major media behind her. Trump threw her badly off stride—just as he did his fellow Republicans—with an unorthodox campaign and a “Homeric use of adjectival epithets.” In the process, he blew up the approved scripts for campaigning, speaking, and debating, earning enemies among opponents and the media that covered him.

Paradoxically, one of the reasons for Trump’s continued popularity is the nearly monolithic hostility of the media, even segments of the conservative media. Hanson, a frequent contributor to conservative publications, aligns himself with no clique or faction, although he seems mildly contemptuous of Never Trumpers. “In the conservative old days,” he writes, “a Republican president could call upon New York and Washington pundits and insiders—in the present generation names like David Brooks, David Frum, Jonah Goldberg, Bill Kristol, Bret Stephens, or George Will—for kitchen cabinet advice. But now they were among Trump’s fiercest critics.”

And in some cases, they have been among the most tasteless. When Melania Trump, recovering from kidney surgery, dropped briefly from sight, “Never-Trumper David Frum wondered whether Trump had struck his wife and sought to cover up the ensuing crime.” Frum wrote: “Suppose President Trump punched the First Lady in the White House (federal property = federal jurisdiction), then ordered the Secret Service to conceal the assault?”

Other Never Trumpers were less nasty, although the objective—discrediting Trump and hoping for his removal—remained steady. From the day Trump was elected, Hanson writes, “David Brooks reassured his depressed readers that Trump would likely either resign or be removed from office before his first year was over.” Nor has that hope faded. Recently we learned that top officials in the FBI had seriously discussed removing him from office—some might call it a coup.

“Never before in the history of the presidency,” Hanson writes, “had a commander in chief earned the antipathy of the vast majority of the media, much of the career establishments of both political parties, the majority of the holders of the nation’s accumulated personal wealth, and the permanent federal bureaucracy.” The deep state and media despised him “because they were often one and the same thing.”

During previous presidencies, with the notable exception of Richard Nixon’s, the media generally observed an unofficial gentlemen’s agreement, holding back stories about JFK’s sexual escapades, for example, and LBJ’s use of his office to increase his wealth. With Nixon, the gloves came off early after he failed to end the Vietnam war during his first term, even though his Democratic predecessors were fully responsible for it.

But thanks to an extraordinary speech on the responsibilities of the media written by Pat Buchanan and delivered by Vice President Spiro Agnew in Des Moines, the press pulled back for a time. Nixon ended the war, and with the overwhelming support of those working-class voters Hillary Clinton would later call “Deplorables,” won a landslide victory in 1972. Ronald Reagan would again demonstrate the electoral power of the Deplorables in 1980.

At the end of two years, this base of support for Trump remains solid. This is in part, Hanson notes, due to Trump’s recognition that “the America ‘era’ was not ending, but at that time enjoying the strongest GDP growth, job reports, energy production, business and consumer confidence, and foreign policy successes in fifteen years.” The latest figures show that this administration’s economic policies have resulted in the highest number of job openings ever recorded in the United States, with more women and minorities employed than ever before.

Moreover, Hanson adds, “It was hard to see how U.S relations with key allies or deterrent stances against enemies were not improved since the years of the Obama situation…no more naïve Russian reset. China was on notice that its trade cheating was no longer tolerable. The asymmetrical Iran deal was over. And the United States was slowly squeezing…a nuclear North Korea.”

How does it end? At the moment, the McGovernite field of Democrats offers little threat to Trump’s reelection in 2020. But reelection or no, perhaps Henry Kissinger, quoted by Hanson, best sums up what Donald Trump may come to represent: “I think Trump may be one of those figures in history who appears from time to time to mark the end of an era and to force it to give up its old pretense.”

John R. Coyne Jr., a former White House speechwriter, is co-author with Linda Bridges of Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement.

No comments:

Post a Comment