By Robbie Millen

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/frederick-forsyth-i-am-not-writing-any-more-novels-the-lust-has-gone-krf8gl2hv

September 22, 2018

There was an explosive RAT-TAT-TAT. “The Outsider” let the violent burst of noise fade. His cold blue eyes surveyed his deadly work. He moved his trigger finger again. Another sharp RAT-TAT-TAT pierced the night. He stopped, taking a moment to admire his trusty weapon. The Nakajima AX-150. Those crafty Japanese, the Outsider mused to himself. With its typing speed of 12 cps, three levels of impression control and automatic centring, it was the most effective typewriter on the market.

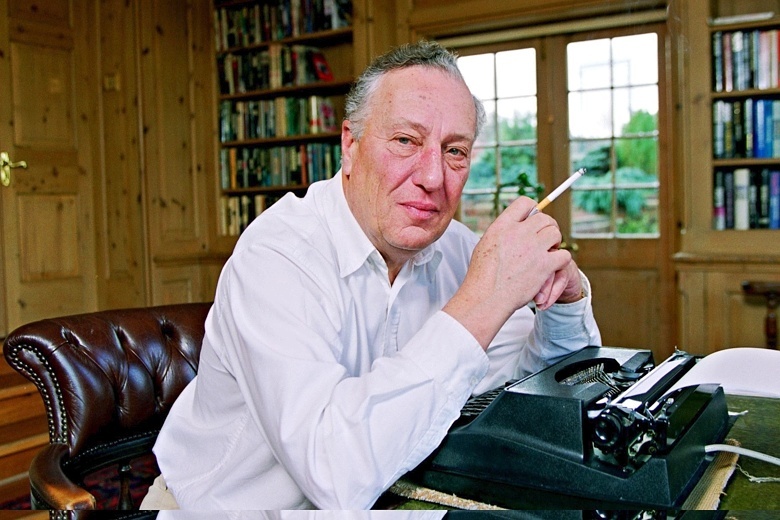

There is something reassuringly old-school about the fact that Frederick Forsyth, a self-confessed “outsider” and two-finger typist, has written his 14th and latest novel on an electronic typewriter. Why shouldn’t The Fox, a thriller about cyberhacking, be created with the aid of typewriter ribbons? Forsyth, who is 80, tells me: “I’ve got three unused typewriters in a cupboard at home — enough to see me out.” He will not be silenced by any impending typewriter shortage.

Forsyth deserves his place among the thriller greats. His first three novels alone —The Day of the Jackal (published in 1971), The Odessa File (1972) and The Dogs of War (1974) — rightly give him silverback status. His great strength is that however fantastical the story might seem at first sniff, it is grounded in hard-nosed fact.

“I found myself saddled after Jackal with the reputation of getting the research right,” he tells me when we meet in a central London hotel. “I went the extra mile to bring in things that would not have been necessary. The minutiae of how a rifle works, how it is put together. It need not be in there, but it is interesting to me.”

The nerdy detail is a Forsythian signature. So in The Fox we learn about the Orsis T-5000 sniper rifle with its DH5-20x56 scope, the HADECS-3 speed cameras, even the difference between various Old Etonian ties (Forsyth went to the distinguished Tonbridge). He is annoyed that he made a small error in the proof of The Fox — he had special forces soldiers using head-mounted penlights. No, his balaclava-wearing sources told him, they would wear night vision goggles.

He is still pleased that when the mercenary Bob Denard launched a coup in the Comoros Islands in the Indian Ocean in 1978 he used The Dogs of War as a blueprint. “Amusingly, as his French mercenaries came up the beach . . . they carried a paperback edition of Les Chiens de Guerre so that they could constantly find out what they were supposed to do next,” Forsyth recounts in his swaggeringly entertaining memoir, The Outsider.

In The Fox, a team of SAS men have to dispatch some foreign agents in the British countryside. A bit implausible? Not at all, he says. “In our own sweet way we do terminations, as the special forces call them. A total wipeout is unusual, but such orders have been ordered discreetly and deniably.” Remember the Loughgall ambush of 1987 in Northern Ireland, when the SAS shot dead eight IRA members, or the ending of the Iranian embassy siege?

He clearly loves the world of cloak and dagger. In conversation he drops in words such as “slotting” (for assassinating), “Bolo” (“be on the look out”) or “The Firm” (MI6). In the late Sixties and onwards, as a journalist, he did unpaid work for MI6. Information gathering, or delivering the odd parcel (letters really are pushed under hotel room doors at midnight). “The thing about using the amateur is that he has got an impenetrable cover. I really am the Reuters correspondent. Check it out.”

Many of his books are set in war zones or involve derring-do, so I ask whether he is a danger junkie drawn to the sound of gunfire. “I always wanted to know what was going on. But the idea of ‘Goody, it’s going to be dangerous.’ No!

“When I was a youngster I had this insatiable curiosity. If I saw a range of hills, I would have to know what was on the other side. If I saw a curve in the river, I had to know what was round the bend,” he says. “And that got me into scrapes — and I managed to get out of them unscathed. There are half a dozen occasions when it could have ended there. But I was very, very lucky. I got through a number of firefights in Biafra and never got touched. Had a man beside me get his head blown away. It could have been my head.”

As he puts it in The Outsider: “During the course of my life, I’ve barely escaped the wrath of an arms dealer in Hamburg, been strafed by a MiG during the Nigerian civil war and landed during a bloody coup in Guinea-Bissau. The Stasi arrested me . . . and a certain attractive Czech secret police agent — well, her actions were a bit more intimate.” All very boy’s own.

Anyhow, he says, “in recent years I’ve been doing novels and haven’t been in any war zones”. Then he remembers that for his thriller The Cobra he arrived in Guinea-Bissau to the sound of rocket-propelled grenades — and for The Kill List, his 2013 thriller, he went to Somalia. “Sandy [Forsyth’s wife] joked, ‘If you ever try anything like that again, I’ll see Fiona Shackleton [the Prince of Wales’s divorce lawyer].’ No more harum-scarum episodes. At 75, you don’t run like you used to.

“What turns me on now? Walking the f***ing dogs,” he says ruefully. He lives in a village outside Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire with Sandy, his wife of 30 years, stepmother to his grown-up sons, and among other things, a former PA to the film directors Nicholas Roeg and Ridley Scott, then Elizabeth Taylor. They have three Jack Russells, including a puppy. “We sleep together — I can’t get a look-in edgeways. There’s a furry bloody head between us. At 80, I’ve been surpassed by a six-month-old.” I suspect age has gentled Forsyth, who in his memoir comes across as gung-ho, rumbustious, forthright, even cocky. He reckons himself to be a quiet chap. Indeed, he is rather self-deprecating.

Back to danger. He reported from Biafra in 1968 for the BBC — and that was when MI6 approached him. Forsyth has trenchant, Brexiteering right-wing views; his weekly column in the Daily Express — “an old codger sounding off from his pulpit”, is how he disarmingly puts it — could curdle the almond milk in a liberal softie’s fair trade coffee. But his views on the civil war in Nigeria show a different side to him.

The Igbo-speaking southeast region had declared independence from the British-backed Nigerian government. A nasty war ensued — in which between 500,000 and 2 million civilians died, many through starvation. “As a journalist of 12 years’ standing, I thought I had few illusions about the mendacity of power, but I had thought that there were certain things the British wouldn’t do. I did not think we would ever help a blood-stained military junta to kill children. It would be like helping Assad today,” he says. He likens the regime’s hatred for Igbos to the Nazi hatred of Jews.

His reports about starving babies were not welcomed by the Foreign Office — or his BBC bosses. “They pretended it was all an invention by people like me. It was a lie, and they knew it was happening.” MI6, he says, was “daggers drawn” with the Foreign Office so, after he was sacked from the BBC (“It’s still moot — I think I walked and my letter of resignation reached them before I was sacked”) he was recruited by MI6 to return to Nigeria “and give them the ammo to turn Harold Wilson” against the Foreign Office line.

It cemented an enduring prejudice against “the Establishment” and its culture of balls-up and cover-up. “Cover-up is part of what they see as their mandate . . . We cannot make a mistake, we will not admit a mistake. [The Foreign Office] said it would be a two-week war. Zero casualties. Two weeks became eight and eight became fifty and so on, and they would not say that had made a mistake.”

Has he ever thought about entering politics? No! “When you join the Establishment, you sacrifice too much. You can’t disagree. You can’t call the boss a fool, you can’t take a different line from the party line. I’ve never lusted for three things. One is power — I’ve never wanted to hire and fire: that cuts out politics, the civil service, commerce and industry. I’ve never lusted for money. I’ve never lusted for fame: that cuts out telly and showbiz.”

What about sex, the fourth great impulse? “Hello, memory lane,” he quips. That reminds me of a funny passage about the popping of his 17-year-old cherry in his memoir: “the only other thing of interest during those ten weeks in the hot, sunny spring of 1956 was a torrid affair with a 35-year-old German countess . . . She taught me many things a lad should know as he steps out on life’s bumpy road. She had the quaint habit of singing the Horst Wessel song during coitus.” Class.

Before he became a journalist, he did his national service with the RAF. As a boy, his heroes were fighter aces. He tells me that in the late 1950s “we used to fly over the North Sea and intercept Russian bombers trying to penetrate our air defences. We would see this bloody great Bison, probably with a nuke on board, and formate on it. And wave at the crew. The Russians never waved back, they would just stare.”

He says he “killed the bug” for flying by doing it. Anyhow, he was not a natural soldier — “the disobedience, it’s inbuilt. Question everything. Complain. Doubt. Disagree” — so he left after two years for “the hazards of the pubs of King’s Lynn” and became a reporter for the Eastern Daily Press.

Becoming a journalist provided him with the material for his first novel. He was a Reuters correspondent in Paris during Charles de Gaulle’s presidency. “France was on the threshold of revolution, civil war maybe, a coup d’état was on the cards.” That was when the idea took shape of a thriller about ultras from the OAS, the Organisation Armée Secrète, opposed to France giving independence to Algeria, hiring an assassin to kill de Gaulle.

By then an ex-BBC reporter, writing The Day of the Jackal was a “a way of getting me out of a jam. The craziest way, most impractical way of trying to settle all my debts. So I dashed off in 35 days this story I had been nurturing for seven years.” Most publishers rejected it, but Hutchinson took the bait. It started to do well.

Later “I was offered a buyout [for Jackal] by Hutchinson —

75,000 quid. It sounded like a very good deal. I got £25,000 for the film rights.” He did not know he had written a thriller classic. “I had to watch them screen and screen, print and print for 50 years. Nothing for old rope. I’m not complaining, I’ve had great luck.”

Indeed, he has had a 47-year-long thriller-writing career. After The Kill List was published five years ago, he said that would be his last novel. Now, he is saying that The Fox will definitely be his last. “You may bury me if I break my word. I am not writing any more novels. The lust has gone. Even the interest has gone. Who wants to bore himself to his grave? One can’t go on for infinity without the quality going.

“Writing [The Fox] was much harder for me than 20 years ago. It drained me completely. The energy is not there.” While he used to manage ten pages of A4 a day, “this was down to five a day”.

Forsyth is not going to chain himself to his typewriter. The motivation has gone — he calls himself a “glorified mercenary” because he writes to earn moolah. “Do I need the money? Nooooo. I was never compulsive about writing. I don’t have a message for the human race.”

I wonder, though, will he really stop? Remember there is a cupboard with three typewriters waiting to be unleashed.

The Fox by Frederick Forsyth is published by Bantam. The author will be in conversation with fellow thriller writer Frank Gardner on Thursday, October 11. cheltenhamfestivals.com

No comments:

Post a Comment