http://www.nytimes.com/

October 3, 2016

Ben Macintyre’s suspenseful new book, “Rogue Heroes,” about the founding of Britain’s S.A.S. during World War II, reads like a mashup of “The Dirty Dozen” and “The Great Escape,” with a sprinkling of “Ocean’s 11” thrown in for good measure. Like earlier Macintyre books set during that war (“Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies” and “Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory”), this volume features an ensemble of eccentrics, mavericks and malcontents. And, in this case, one visionary, David Stirling, who invented an elite commando unit that would become the prototype for a new kind of modern warfare, and the model for special forces around the world, including the Navy SEALs and the Army’s Delta Force.

In 1941, Mr. Stirling, an aristocratic dilettante who found his calling as a soldier, was recuperating in a Cairo hospital from injuries sustained during an ill-judged parachute jump. Studying a map of North Africa — where British forces were facing off against Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps — it occurred to Mr. Stirling that small groups of highly trained commandos could operate behind German lines, sabotaging aircraft, runways and fuel depots. Looking for men who could extract “the maximum out of surprise and guile,” he sought soldiers who exhibited independence and self-reliance.

“Recruits tended to be unusual to the point of eccentricity,” Mr. Macintyre writes, “people who did not fit easily into the ranks of the regular army, rogues and reprobates with an instinct for covert war and little time for convention, part soldiers and part spies; rogue warriors.”

Mr. Macintyre draws sharp, Dickensian portraits of these men, and he displays his usual gifts here for creating a cinematic narrative that races along, as Mr. Stirling’s crews find themselves in one harrowing situation after another — trudging through blazing desert heat with precious little water or food; desperately trying to elude snipers and ambushes as they rush to blow up German airplanes and supply lines; attempting to extricate themselves from dire predicaments that would test the resourcefulness, never mind stiff upper lip, of James Bond.

Because this history of S.A.S. (Special Air Service) during World War II — based on documents compiled as the “SAS War Diary” and made public in 2011 — is episodic, it lacks the coherence of Mr. Macintyre’s earlier books, which focused on a particular mission or central character. The colorful Mr. Stirling and his co-conspirator in founding S.A.S., Jock Lewes (who was as austere and disciplined as Mr. Stirling was fond of drink and gambling), only intermittently hold center stage, and many of the men they recruit suffer horrific deaths not long after we get to know them. Besides Mr. Lewes and Mr. Stirling, the one team member who remains firmly wedged in our minds is Paddy Mayne,who has a capacity for “devotion on an almost spiritual level” but is also given to terrifying bursts of violence on the battlefield and off.

Mr. Macintyre is masterly in using details to illustrate his heroes’ bravery, élan and dogged perseverance. He makes us feel the “constructive brutality” of the training that recruits endured — marching up to 100 miles through the desert, carrying a full load of equipment and prohibited from taking a drink of water until the trek’s end. He describes men who died — or were horribly injured — during missions and had to be left behind. And he conveys both the heart-stopping horrors of combat — one fight left 21 men dead, 24 wounded, 23 as prisoners — and the plucky, schoolboy spirit that emerged as their default setting.

“Stirling never relaxed his dress code,” Mr. Macintyre writes. “Whether going into battle or unwinding after it, he always wore a tie. The men chatted idly in the heat, using a shared jargon, weighted with euphemism, black humor, and profanity, a private language unintelligible to a stranger: heading into the desert was ‘going up the blue’; a raid was ‘a party’ or ‘jolly’; grumbling was ‘ticking’; sinking into sand was ‘crash diving’ or ‘periscope work.’”

While individual S.A.S. sabotage and reconnaissance missions (in Libya, Egypt, Italy, France and Germany) are evoked with considerable verisimilitude, Mr. Macintyre has difficulty zooming out from his heroes’ story to give a broader understanding of how their operational work fit into the larger canvas of the war. The story of what happened to the S.A.S. at war’s end feels truncated and rushed, as does the story of how it would be resurrected and copied around the world. At the same time, the book never delves into the mind-set of special forces soldiers with the power and immediacy of “No Easy Day” by Mark Owen (a.k.a., Matt Bissonnette, a member of the Navy SEAL Team 6, which took out Osama bin Laden).

What “Rogue Heroes” does do is provide a gripping account of the early days of S.A.S. and some understanding of just how rapidly it revolutionized a form of modern war that has grown ever more important as governments seek to find alternatives to traditional and costly wars of occupation.

Follow Michiko Kakutani on Twitter: @michikokakutani

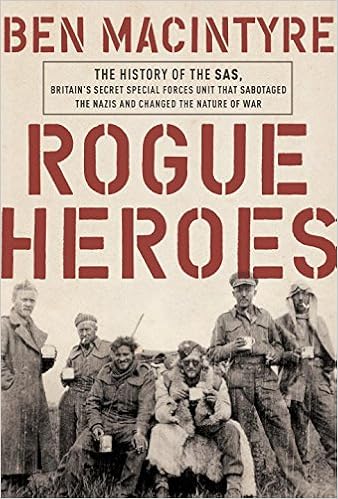

Rogue Heroes

The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War

By Ben Macintyre

Illustrated. 380 pages. Crown. $28.

No comments:

Post a Comment