By JOE DRAPE

The New York Times

Published: December 28, 2006

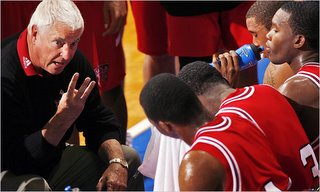

It is not surprising that Bob Knight says his favorite song is “My Way,” or that when his time on earth is over he hopes for this epitaph: “He was honest.” Until then, however, he must be satisfied with assessing his impact on the game of basketball.

With one more victory — his 880th — Knight will pass the former North Carolina Coach Dean Smith for the most career wins in N.C.A.A. Division I men’s basketball. It can come today, when his Texas Tech Red Raiders play host to Nevada-Las Vegas in Lubbock, Tex., and will be the crowning achievement on a 41-year career filled with them: five Final Four appearances, three national titles, an Olympic gold medal as the coach of the 1984 United States team and a spot in the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1991.

Knight, 66, says he has thought about his coaching legacy. In fact, he said, he first gave it serious thought more than 20 years ago when he was considering jumping to the N.B.A. He asked his friend, the Hall of Fame Coach Pete Newell, for advice. Newell asked Knight what he wanted from coaching.

“I told him that I wanted to be thought of by other coaches the same way that you are thought of,” Knight said in a recent telephone interview.

He still does.

“I want them to know that I am a guy who watches more film than anyone, who cared if I could find a way to take advantage of a weakness in an opponent so I could beat them,” he said. “I want them to know I’m a teacher.”

In coaching circles, Knight’s legacy appears to be intact.

His former players make up a who’s who list in coaching, including Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski, Iowa’s Steve Alford and the Knicks’ Isiah Thomas. Even longtime rivals concede Knight’s name is synonymous with the “part-whole” method of teaching, man-to-man defense and the motion offense. All ascribe a virtue to Knight that is perhaps at odds with his public image: patience.

Still, some worry that Knight’s coaching accomplishments have been eclipsed by his often profane and highly publicized tantrums, which include throwing a chair onto the court during a game against Purdue and a run in with a police officer in Puerto Rico, and especially his dismissal from Indiana in 2000 after 29 seasons in the wake of a confrontation with a student.

“Here is one of the great minds in basketball,” said Quinn Buckner, the point guard for Knight’s 1976 Indiana team that won the national championship and posted a perfect record. “He has graduated all of his players, and never had trouble with the N.C.A.A. And unfortunately, because of the way things have transpired, I don’t think this record, and the impact that he had on so many young people’s lives, will ever be fully appreciated.”

Knight, however, is not one of the worried. He has conceded the battle for public opinion and insists that he has no regrets about how he has conducted himself on or off the basketball court.

“You don’t find any kid who’s ever played for me, or any coach who’s coached with me saying these things,” said Knight who began his head coaching career at Army. “They are who I’m answerable to. I’ve done what I thought I’ve had to do, and haven’t worried about what other people think.”

Instead, Knight gets a measure of his impact on basketball in his frequent conversations with Alford or Lawrence Frank, his former student-manager at Indiana who now coaches the Nets.

Both employ the “part-whole” method of instruction that they learned from Knight, who had absorbed it from Newell. It is a simple technique grounded in fundamentals.

“You break it down in pieces,” Frank said. “You make sure each player knows what he must do in a one-on-one, two-on-two, three-on-three. By the time you get to five-on-five, everyone has a high level of understanding and confidence. I have never seen a coach so committed to turning over every stone to find an answer.”

Before practices at Iowa, Alford finds himself laying the tape down the center of the lane just as Knight does to remind his players where to help their teammates on defense. He starts practices with the same four-corner passing drill that he did as a player at Indiana. He frequently utters to his Hawkeyes one of Knight’s famous rules: They must make four passes before someone shoots.

“Look at how much has changed,” said Alford, who intended to be in Lubbock to see Knight perhaps break the record. “Coach won games when there was no shot clock, when there was a 45-second shot clock and now a 35-second clock. But really, he has never changed in his coaching style or personality. He always has known who he was and has never wavered.”

Newell, 91, says every basketball coach at any level is indebted to Knight for refining what is by far the most popular offense in the game: the motion offense, which is based on ball movement, screens and spacing.

“Bob is a great clinician,” Newell said. “and over the years, he has spent countless hours with other coaches teaching his philosophy. It doesn’t matter if you’re a youth league or high school coach, Bob will take his time telling you exactly what he does and why he does it. He’s one of the few coaches that doesn’t believe in keeping secrets, and he has a gift for imparting them clearly.”

While virtually every team runs some form of a motion offense, not many of them do it as proficiently as a team coached by Knight.

“The six years I was in the Big 12 with him, I thought Texas Tech was the toughest team to prepare for because of how they ran their motion,” said Kelvin Sampson, who coached at Oklahoma before taking over Indiana this season. “They made hard cuts and were a good passing team. They knew when to attack off the dribble, got you in angles and attacked you in different areas. He does such a great job of discipline and shot selection. They may get a shot within five or six seconds or get a shot in 30 seconds. They take what you give them. I think his motion offense and the discipline of his teams have always set him apart.”

It is Knight’s insistence on discipline, and the manner in which he enforces it, that has brought him the most unflattering scrutiny. He can be bellicose and was caught on videotape grabbing the neck of one of his former players at practice, which precipitated his dismissal at Indiana.

Buckner, now a broadcaster for the Indiana Pacers, concedes Knight was a demanding coach.

“We were not a democracy, but he was fair,” Buckner said. “Coach was exceptional at pushing our buttons. I can’t say that every day I liked it. But we trusted him and knew that he was not there to put us in peril. Looking back on it, I can say that he helped make me a man and prepared me for life far beyond basketball.”

Knight remains a private man, especially when it comes to what his friends and former players say are his many acts of kindness.

For Frank, he made dozens of phone calls behind the scenes to jump start his coaching career.

“I found out about them months, sometimes years later,” Frank said.

But for Landon Turner, one of the stars of Indiana’s 1981 team, Knight’s devotion to his players became public. Four months after the Hoosiers captured the national title, Turner was paralyzed in a car accident. Knight tirelessly raised money for Turner’s hospital bills and pushed him to resume his life.

“I will always be in debt to him,” said Turner, now a motivational speaker in Indianapolis. “The money meant a whole lot, but really the most important thing he did was not treat me any differently. He still challenged me and cussed me out. I love him for that.”

Ultimately, Knight believes he is accountable only to the players he has coached at Army, Indiana and Texas Tech and the friends he has made over the years in coaching and beyond. He is proud of the record he is about to set and honored to be in the company of revered coaches like Smith, Adolph Rupp and John Wooden. Still, he is not sure of how accurate the record is at measuring how successful he has been in pursuing his passion.

“Maybe I’d be more impressed if I won that many high school games,” he said. “That’s where the real coaching is done. You take the talent that lives in the area and mold them into a team.”

Thayer Evans contributed reporting.

No comments:

Post a Comment