By John Timpane

https://www.inquirer.com/arts/books/mark-kram-smokin-joe-frazier-book-philadelphia-free-library-20190610.html

June 10, 2019

Mark Kram Jr. says that heavyweight great Joe Frazier (1944-2011), who came from South Carolina to become a hometown hero, was “the ideal champion for Philadelphia, the perfect fighter for this town.”

“He worked hard, very hard, and you could see his pride in what he did,“ Kram says over a coffee at La Colombe on Independence Mall. “He might win or he might lose, but he wasn’t going to step back for anything. Life could hit him as hard as it wanted, and he kept coming on. That was his style, and that’s how he did everything.”

Which brings Kram to a central point about Smokin’ Joe, and Philadelphians: “That’s what makes us human. We all face, in our own ways, terrific obstacles every day. But we don’t quit. We keep going at it.”

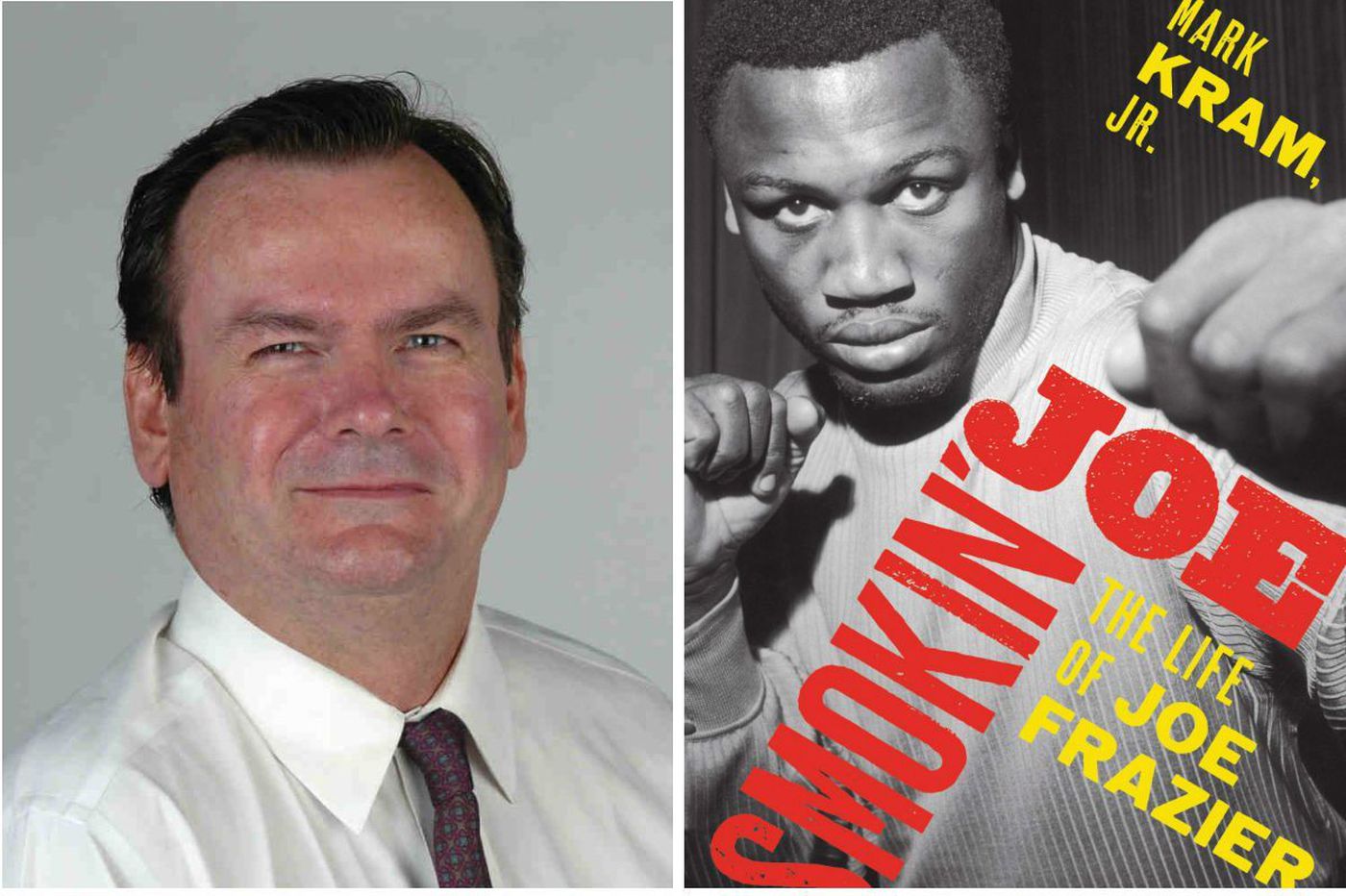

That determination and fury come through in Kram’s new biography, Smokin’ Joe: The Life of Joe Frazier. In it, Kram deploys all the skills and experience gained during his 1987-2013 tenure at the Daily News. He is the son of Mark Kram Sr., who covered Muhammad Ali for Sports Illustrated from 1964-1977 and wrote the 2001 book Ghosts of Manila, about Ali’s trio of fights with Frazier. The junior Kram happily reports that in working up his own book, he revisited, “with very real delight,” the celebrated work of Daily News sports writers such as Larry Merchant and Stan Hochman.

Why Joe Frazier now?

I’m a freelance writer these days, and one day, the idea of Joe came to me. He’s been much written about, to be sure. I wrote about him a lot at the Daily News and had many experiences with him. But a true biography, I felt, had not yet been done. In 2015 I was in my office, and I got the chills, as if some cosmic traffic light was turning from red to green. I thought, “In 10 years someone’s going to write his life, but by then many people will be gone who are relevant to his story. I have to do this now, while there are still primary sources, people who knew him and can talk about him. I wanted to step back and ask, “What were the complexities in this man and his life?” And believe me, there were many.

Whom did you go to first?

I called Denise Menz, his longtime companion for 40-plus years; and then his daughter, Weatta Frazier Collins, and they opened the doors for me. I had long conversations with people like Martha (Maizie) Rhodan, his last living sibling, who filled in a lot of holes. On that foundation, I began to report it as you would a takeout for the paper.

What were some of those complexities?

When you look at where he came from, this poor dirt farm in South Carolina, with a father who had an idea of maleness that he passed down to his son … and you think of Joe’s travels, from there to Philadelphia, to the Olympic Games, to stardom, to the very top. You see the anger, the maybe-too-much pleasure in partying, the parental and spousal issues, you see those things — and then you see another man.

Another man?

He was fundamentally a very big-hearted man. In the prologue, I tell the story of him driving down Broad Street, going to Atlantic City, and he sees a legless man in a wheelchair, with a can of kerosene in his lap, and Joe stops and takes him home. And he tells his boys: “This is what a man does.” He pulled money out of his sock and helped strangers he met. He visited the hospital and used to sit with the cancer patients and cry. Toward the end of his life, he forgives his manager, Eddie Futch, who he felt had ended the third Ali fight too soon. And there’s, finally, a climactic scene with Ali. Those scenes go right to his character.

Frazier will inevitably be linked with Ali, whom he beat for the first time in Ali’s career in 1970, and from whom he absorbed two murderous beatings in 1975. The book is about Frazier, but their relationship is an important through line in your story.

Joe says it himself at one point: “He said once I would have been nothing without him. But what would he have been without me?” You could argue he resurrected Ali, only to knock him on his can. And his fury at Ali in and out of the ring, it went far beyond Ali. It went back to Frazier’s beginnings, his upbringing, the hard life and hard work, the sense of being seen as less-than.

The arc of a prizefighter’s life is so often tragic. Ali is the best-known example. But you don’t see Frazier’s life as tragic.

Joe was much beloved. As a fighter, he had this get-there-early-stay-there-late ethic, so much in evidence in his work at the gym on Broad Street. Was there diminishment, in the latter stages of his career, and in his final years? Yes, there was diminishment. But he left a mark upon this city, and many people really loved Joe Frazier. Joe was seen as the ultimate overachiever, almost a symbol of the city. On a person-to-person level, he inspired affection and gratitude in hundreds of people. No one is calling him perfect; far from it. But any life like his, you can’t call that tragic.

No comments:

Post a Comment