July 12, 2019

It is difficult to know where to begin when writing about Jim Bouton, who died Wednesday at age 80. If he had never written “Ball Four,” Bouton would no doubt have still merited a New York Times obituary as a former Yankees pitcher who won 21 games in 1963 and 18 in 1964, then tacked on two World Series wins that October.

But a sore arm cost Bouton his fastball and caused him to end up pitching as a 30-year-old knuckleballer for the expansion Seattle Pilots at the start of the 1969 season. It was also probably the reason he was willing to team with longtime sportswriter Leonard Shecter on a book chronicling that season. Before it was over, Bouton had been sent to Class AAA Vancouver, returned to Seattle and then been traded to Houston.

Bouton never stopped taking notes. A year later, “Ball Four,” written in diary form, was published and became arguably the most iconic baseball book ever written. Some will argue for Roger Kahn’s lyrically brilliant “The Boys of Summer,” but nothing changed baseball or sports journalism as much as Bouton’s seminal work.

Never had an athlete written with as much honesty, candor and humor about what life was like inside a locker room. People often compare “Ball Four” to Jim Brosnan’s ‘The Long Season,” written 10 years earlier, and there’s certainly common ground. But “Ball Four” went to places no athlete had previously gone.

Bouton shocked people by writing honestly about good ol’ boy Yankee Mickey Mantle — not so much about his home runs but rather his drinking, womanizing and mean streak. His description of joining Yankees teammates on the roof of Washington’s Shoreham Hotel to “beaver-shoot” — check out women through their hotel windows — would be unacceptable in today’s world, and Bouton’s revelation of it infuriated baseball insiders.

New York Yankee starting pitchers left to right, Whitey Ford, Jim Bouton, Al Downing, Ralph Terry, and Stan Williams, September 4, 1963.

Bouton took ordinary players and made them into icons: journeyman pitcher Gary Bell yelling, “Smoke ’em inside,” as his scouting report for every hitter in baseball; Alvin Dark’s famous “take a hike, son,” remark to an autograph seeker; Jim Gosger’s “yeah-surre” comment as he burst from a hotel-room closet during a tryst between his roommate and a young woman.

And, of course, there was Seattle Manager Joe Schultz’s “Let’s go pound some Budweiser” war cry and his ability to repeat his two favorite profane words in, as Bouton wrote, “all their possible combinations.”

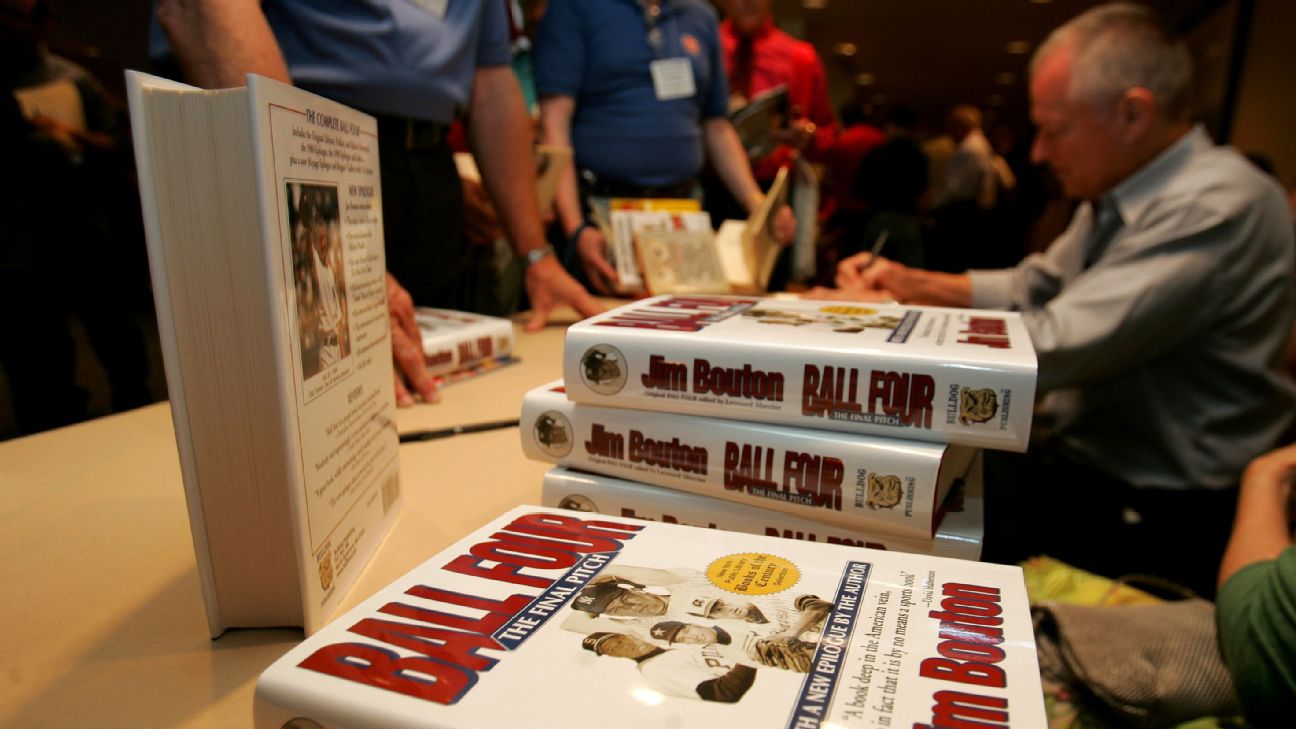

“Ball Four” has sold more than 5 million copies — Bouton updated it often — so there are plenty of people who will know those anecdotes and many more by heart.

The book also made Bouton into a baseball pariah.When it came out in 1970, he was reprimanded by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who called the book “detrimental to baseball.” Kuhn also asked Bouton to sign a statement saying that the book was fiction. Bouton, naturally, refused.

Kuhn was hardly the only one to take issue with it. Players and many longtime baseball writers, some of whom considered themselves part of their teams, agreed with Kuhn.

(AP/Jim Lent)

No doubt many writers were simply jealous. In those days, with the wide-open access the media had, a good reporter could have told many of the same stories that Bouton told. But no one wanted to be drummed from the fraternity.

The irony is that few loved baseball more than Bouton. He made a comeback with the Atlanta Braves in 1978 — eight years after first leaving the game — and pitched in semipro leagues into his 50s. The final line of “Ball Four” poignantly expresses Bouton’s feeling about the game: “You see,” he wrote, “You spend a good deal of your life gripping a baseball and, in the end, it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

He also wrote often about sometimes “forgetting to tingle” as he walked across the outfield grass to the bullpen before a game, reminding himself how lucky he was to make a living playing baseball.

Bouton wrote a number of other books, including “Foul Ball,” about his efforts to save a minor league ballpark in Pittsfield, Mass., where he had settled after retirement. The book was written in the same diary form as “Ball Four” and, although the topic was completely different, had the same funny, anecdotal feel to it.

The book was also poignant. Bouton describes the death, in 1997, of his daughter Laurie in a car accident. He also addressed a New York Times op-ed written by his son Michael pleading with the Yankees to release him from baseball purgatory and invite him to Old-Timers’ Day. The Yankees relented and invited Bouton, who joyfully recounts his return to the Yankees’ clubhouse and the mixed reactions of his former teammates.

I wrote a favorable review of “Foul Ball” and was thrilled when Bouton reached out to thank me. That began a sporadic friendship, most of it on the phone. I loved hearing Bouton’s views of baseball today and his stories about old friends and teammates who had stayed in touch.

Bouton isn’t a Hall of Famer, but baseball should find a way to pay tribute to him and acknowledge, almost 50 years later, his massive influence on the game.

As for sports journalism, we were all influenced by him — whether my colleagues want to admit it or not. Bouton proved the importance of firsthand reporting, of truly getting inside a subject. No book — other than “All the President’s Men” — influenced me more as a reporter. Woodward, Bernstein, Bouton — pretty good role models.

Bouton did one other thing for me. Whenever I’m having a tough day at a ballgame — because of a rain delay, or because someone refused to talk to me or failed to show up for a scheduled interview, or an editor is being difficult (yes, it happens) — I look around and I think about what Bouton would have said.

“Don’t forget to tingle.”

Thanks, Jim.

For more by John Feinstein, visit washingtonpost.com/feinstein

No comments:

Post a Comment