Caleb Crain

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/what-were-reading-charles-williams?fbclid=IwAR05aXslT6Dt3gBVrqiPrQGYNcKcOkY0bnxFllHIV_5ve0yV69F1MUddKTs

March 14, 2013

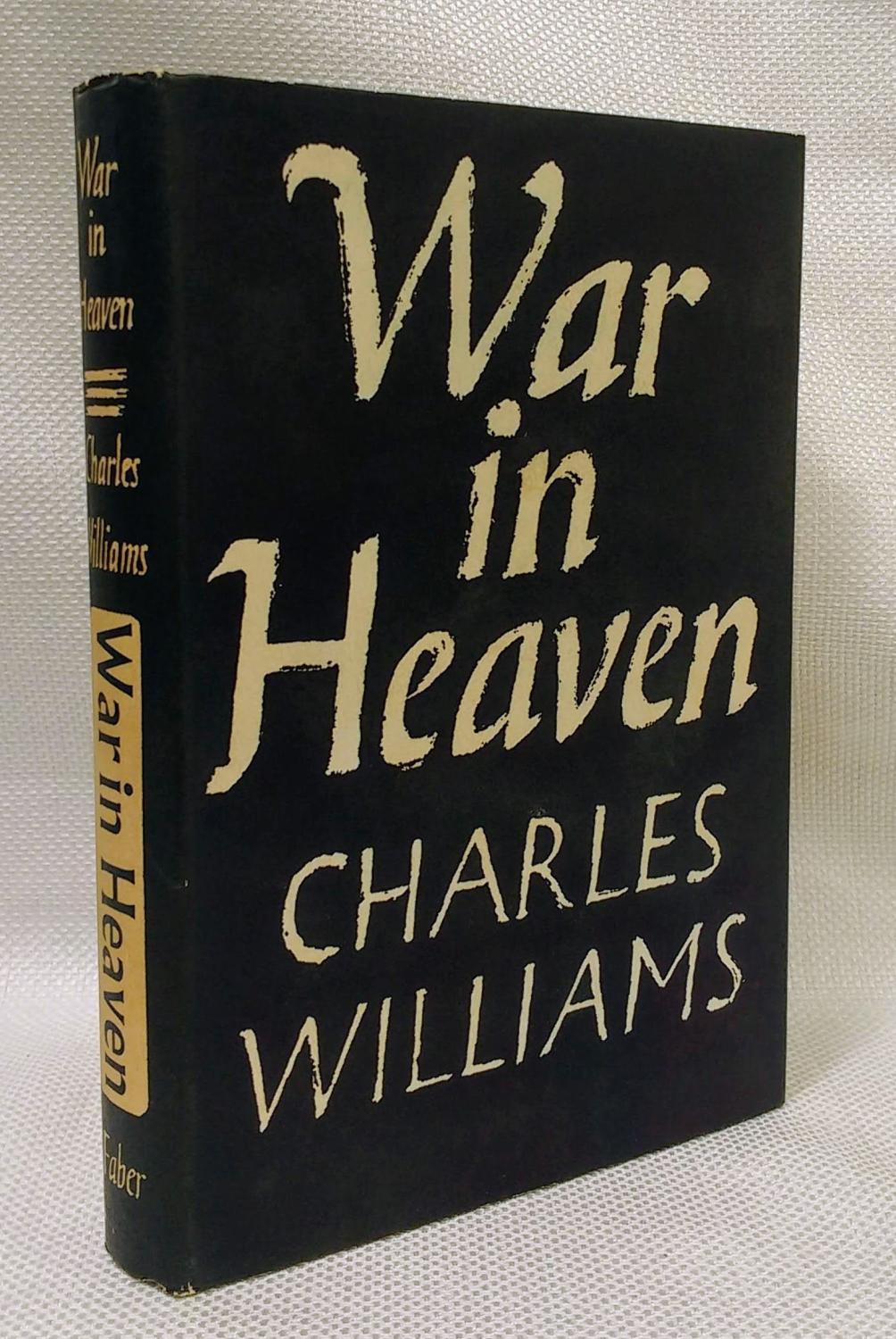

Last weekend, at a used-book store, I picked up a quaint little hardcover Faber & Faber 1954 reprint of Charles Williams’s 1930 novel “War in Heaven.” In its opening pages, a corpse is discovered under an editor’s desk at a publishing house. A chapter later, a postcard from one of the publishing house’s authors demands, with mysterious urgency, the deletion from his page proofs of a paragraph about the Holy Grail. The Grail, according to the to-be-deleted paragraph, may reside today in a church in the parish of Fardles, a short commute from the city. Are the murder and the chalice somehow linked? If Muriel Spark had drunk a little too much Sir Thomas Malory, she might have written something like this. I was incapable of resistance. I bought it.

I knew I had heard of Williams before, but I couldn’t, on the spot, remember where. The jacket copy, anonymous but evidently written by the Faber editor T. S. Eliot, described Williams’s novels as “supernatural thrillers.” The jacket also credited Williams with having written “The Descent of the Dove: A Short History of the Holy Spirit in the Church,” which—I learned when I got home to the Internet—Auden claimed to have re-read once a year. A resort to our bookshelves turned up more data. In the critical study “Later Auden,” Edward Mendelson relays Auden’s report that he felt sanctified in Williams’s presence: “I felt transformed into a person who was incapable of doing or thinking anything base or unloving.” Curiouser and curiouser. A re-perusal of “The Magician’s Book,” Laura Miller’s account of her reading of C. S. Lewis’s Narnia chronicles, reminded me where I’d heard of Williams before. He was one of the Inklings, a group that included Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. More precisely, Williams was a friend of Lewis’s and a rival of Tolkien’s. According to Miller, Lewis thought Williams “godlike,” and Eliot thought he approximated a saint, but Tolkien, though he liked Williams well enough as a person, thought his literary influence was baleful. He ruined Lewis’s sci-fi novel “That Hideous Strength,” in Tolkien’s opinion.

Now that I’ve read “War in Heaven”—some thirty years after reading Lewis’s “That Hideous Strength,” for the record—I have to say that Tolkien had a point. “That Hideous Strength” is deeply Williamsian. And I’m not sure that a Williamsian novel is altogether the sort of thing I enjoy. I read “War in Heaven” compulsively, I admit. Good versus evil makes for a lively story, and a person like me always wants to know what happens to the Grail. I was charmed, moreover, by the bumbling archdeacon who has written a treatise on the League of Nations, and by the way a Catholic duke and an agnostic assistant editor fall into sodality when they discover they both know George Chapman’s poetry by heart.

But the book isn’t all small-town British eccentrics. Its plot is driven by a florid sadist who has designs on a defenseless child, up to and including human sacrifice, and I found myself setting down the book out of excessive dread as often as I picked it up out of unsatifised curiosity. The logic that governs the black magic—its theology, for lack of a better word—seems muddled. At times, the archdeacon seems to believe that he needn’t worry too much if the Grail falls into the wrong hands because Satanism has no power in and of itself, and at one point, in the presence of the novel’s chief Satanist, an assistant editor goes so far as to diss Satanism as “the clerk at the brothel” of belief. Surely these are orthodox opinions, as far as Christianity and science go, but in Williams’s supernatural thriller, by generic necessity heterodox, floor chalkings can be lethal, whole buildings can be hidden by conjured-up fog, and evil people are capable of using the Grail for evil purposes. I found it quite upsetting when the bad guys tried to use the Grail to cement an eternal Mezentian gay marriage between the archdeacon and the lost soul of a masochist. The psychodynamics of the relationship are imagined with a telling and disconcerting vividness. Neither your vicar nor queer theory would approve.

The Grail that I remember from Malory was never so merely instrumental; its purity was unassailable. By the end of “War in Heaven,” I found myself sharing with Tolkien a certain aesthetic distaste for Williams’s imagination. Which made it somewhat puzzling that what Williams’s Grail most reminded me of was… Tolkien’s Ring. Like the Ring, Williams’s Grail grants to knowledgeable users the faculty of vision at a distance. Like the Ring, its possession can be sensed by others who have possessed it. And like the Ring, it is capable of imparting tremendous power. The resemblance seemed to me most striking when a nihilist in Williams’s novel urges a Satanist to destroy the Grail.

“Destroy it!” the Satanist wails in protest. “But there are a hundred things to do with it.”

“That’s the treachery,” the nihilist replies. “Keep it for this, keep it for that. Destroy it, I tell you; while you keep anything for a reason you are not wholly ours.”

The exchange could have been lifted from Gandalf and Frodo’s in the second chapter of “The Lord of the Rings.” “Do not tempt me!” Gandalf insists when Frodo offers to hand the Ring over to him. “The way of the Ring to my heart is by pity, pity for weakness and the desire of strength to do good. Do not tempt me! I dare not take it, not even to keep it safe, unused. The wish to wield it would be too great for my strength.” In these passages, the Grail and the Ring are almost perfect mirror images: Williams’s Grail is dangerous even to the most dedicated of Satanists because, though it can be used for evil, it has an inherent bent for good. And Tolkien’s Ring is dangerous even to the most virtuous of wizards because, though it can be used for good, it has an inherent bent for evil.

Had Williams sensed Tolkien’s disapproval, and was he having a laugh at Tolkien’s expense? Chronology overthrows the hypothesis. Williams published “War in Heaven” in 1930, and Tolkien wrote “The Lord of the Rings” between 1936 and 1949. Maybe the resemblance is no more than coincidence. Or maybe, once my stomach settles, I should read another Williams novel—the other one I bought last weekend seems to be about a platonically ideal lion, and happens to have been published nineteen years prior to “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”—and see what else I find.

No comments:

Post a Comment